Key points

- •

The Le Fort III osteotomy is a technique used in managing midfacial hypoplasia as often seen in syndromic patients.

- •

The subcranial Le Fort III is the classic solution to total midfacial hypoplasia.

- •

The modified Le Fort III is used where the nasal subunit is not involved.

- •

The Le Fort II osteotomy is well-suited for nasomaxillary hypoplasia, where there is less involvement of the orbits and zygomas.

Introduction

Le Fort III osteotomy

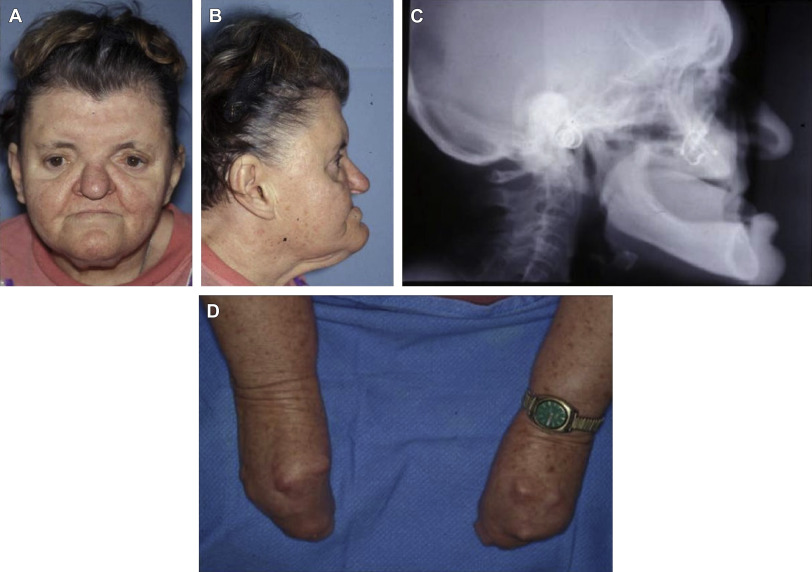

The aesthetic stigmata and functional impairments associated with craniofacial and maxillofacial deformities have long challenged surgeons in the management of deficiencies of the middle third of the face. The French anatomist Rene Le Fort published his classic treatise on the description of common fracture patterns in the middle facial third in 1901. The ensuing World Wars produced horrendous mass casualties that steered facial reconstructive surgeons like Kazanjian in their efforts to manage injuries of the middle third of the face. Building on the knowledge and skill borne by these conflicts, Sir Harold Gillies was the first surgeon to publish an attempt at mobilization of the midface in the management of a patient with craniofacial dysostosis. The procedure was unsuccessful and was abandoned by Gillies. Subsequently, Longacre attempted reconstruction of the midface in patients with craniosynostosis by autogenous rib grafting. This procedure did nothing to address the functional impairments associated with total midface deficiency and, furthermore, resorption of the grafts occurred. The long-term stability of the reconstruction from an aesthetic standpoint was questionable. In 1967, the pioneering efforts of Tessier revolutionized management of the patient with total midface deficiency. His landmark presentations and publications describing the mobilization of the entire middle face through the concept of combined intracranial and extracranial approach in a safe and consistent manner was groundbreaking. Modifications and extensions of this concept by Tessier and others have produced surgical techniques that have provided relief of functional impairments and facial aesthetics to the benefit of the patient with severe midface deficiency. The first known performance of this surgery in the United States was undertaken by Dr Robert V. Walker in 1967, shortly after Tessier’s presentation in Rome at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas, Texas ( Fig. 1 ).

Le Fort II osteotomy

There is a paucity of literature on the Le Fort II osteotomy when compared with the Le Fort III osteotomy. Although the Le Fort III osteotomy is a “high-level” craniofacial disjunction with the potential to move the entire midface forward, useful for total midface hypoplasia (such as the patient with Crouzon syndrome), the Le Fort II osteotomy addresses nasomaxillary hypoplasia in which the central face is more retruded than the orbits and zygomas. This may be seen, for instance, more commonly in Apert syndrome. Typically, these patients may present with a Class III malocclusion, decreased Sella, Nasion, A point, a short nose, and a vertically deficient midface. The Le Fort II osteotomy thus addresses the nose and maxilla, in contrast to nose, maxilla, orbits, and cheeks in the Le Fort III osteotomy.

Based on 30 years of experience, Lakin and Kawamoto delineate the types of nasomaxillary hypoplasia that may benefit from a Le Fort II osteotomy, including lateral nasomaxillary deviation, noncleft nasomaxillary hypoplasia, cleft nasomaxillary hypoplasia, anteroposterior displacement in binder syndrome, and posttraumatic defects. In the case of lateral nasomaxillary deviation, patients experience asymmetric hypoplasia with nasal deviation to the right or left. Patients with lateral nasomaxillary deviation in this series included those with unilateral coronal synostosis, hemifacial microsomia, and Romberg disease.

Steinhauser summarized the variations in the Le Fort II osteotomy, including the anterior Le Fort II as described by Converse in 1971, the pyramidal Le Fort II described by Henderson and Jackson in 1973, and the quadrangular Le Fort II osteotomy described by Kufner in 1971. The latter excludes the nasal skeleton, and is thus used in patients with a maxillary zygomatic deficiency, and normal nasoethmoid projection. The osteotomies of the quadrangular variant share characteristics of both Le Fort I and Le Fort II patterns and do not represent a classic Le Fort II. The anterior Le Fort II includes an osteotomy through the palate at the level of the bicuspid, thus creating an alveolar gap with advancement.

As can be expected, access to the bony skeleton requires a combination of incisions. Access to the maxilla is standard via vestibular incisions. For access to the nasofrontal region and medial orbit, direct cutaneous incisions over the nasal bridge were previously used. The trap door inverted V-Y by Converse is one such example. Perhaps more aesthetic incisions in this area are now hidden in the eyelids via a medial upper blepharoplasty incision or lower transconjunctival approach. Wedgewood describes an approach in which rhinoplasty incisions (transfixion, intercartilaginous) are combined with the intraoral incision to expose all osteotomy sites with a similar goal of minimizing cutaneous scarring. For broad access, a bicoronal may be combined with the intraoral incision, although it arguably carries significantly greater morbidity.

Introduction

Le Fort III osteotomy

The aesthetic stigmata and functional impairments associated with craniofacial and maxillofacial deformities have long challenged surgeons in the management of deficiencies of the middle third of the face. The French anatomist Rene Le Fort published his classic treatise on the description of common fracture patterns in the middle facial third in 1901. The ensuing World Wars produced horrendous mass casualties that steered facial reconstructive surgeons like Kazanjian in their efforts to manage injuries of the middle third of the face. Building on the knowledge and skill borne by these conflicts, Sir Harold Gillies was the first surgeon to publish an attempt at mobilization of the midface in the management of a patient with craniofacial dysostosis. The procedure was unsuccessful and was abandoned by Gillies. Subsequently, Longacre attempted reconstruction of the midface in patients with craniosynostosis by autogenous rib grafting. This procedure did nothing to address the functional impairments associated with total midface deficiency and, furthermore, resorption of the grafts occurred. The long-term stability of the reconstruction from an aesthetic standpoint was questionable. In 1967, the pioneering efforts of Tessier revolutionized management of the patient with total midface deficiency. His landmark presentations and publications describing the mobilization of the entire middle face through the concept of combined intracranial and extracranial approach in a safe and consistent manner was groundbreaking. Modifications and extensions of this concept by Tessier and others have produced surgical techniques that have provided relief of functional impairments and facial aesthetics to the benefit of the patient with severe midface deficiency. The first known performance of this surgery in the United States was undertaken by Dr Robert V. Walker in 1967, shortly after Tessier’s presentation in Rome at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas, Texas ( Fig. 1 ).

Le Fort II osteotomy

There is a paucity of literature on the Le Fort II osteotomy when compared with the Le Fort III osteotomy. Although the Le Fort III osteotomy is a “high-level” craniofacial disjunction with the potential to move the entire midface forward, useful for total midface hypoplasia (such as the patient with Crouzon syndrome), the Le Fort II osteotomy addresses nasomaxillary hypoplasia in which the central face is more retruded than the orbits and zygomas. This may be seen, for instance, more commonly in Apert syndrome. Typically, these patients may present with a Class III malocclusion, decreased Sella, Nasion, A point, a short nose, and a vertically deficient midface. The Le Fort II osteotomy thus addresses the nose and maxilla, in contrast to nose, maxilla, orbits, and cheeks in the Le Fort III osteotomy.

Based on 30 years of experience, Lakin and Kawamoto delineate the types of nasomaxillary hypoplasia that may benefit from a Le Fort II osteotomy, including lateral nasomaxillary deviation, noncleft nasomaxillary hypoplasia, cleft nasomaxillary hypoplasia, anteroposterior displacement in binder syndrome, and posttraumatic defects. In the case of lateral nasomaxillary deviation, patients experience asymmetric hypoplasia with nasal deviation to the right or left. Patients with lateral nasomaxillary deviation in this series included those with unilateral coronal synostosis, hemifacial microsomia, and Romberg disease.

Steinhauser summarized the variations in the Le Fort II osteotomy, including the anterior Le Fort II as described by Converse in 1971, the pyramidal Le Fort II described by Henderson and Jackson in 1973, and the quadrangular Le Fort II osteotomy described by Kufner in 1971. The latter excludes the nasal skeleton, and is thus used in patients with a maxillary zygomatic deficiency, and normal nasoethmoid projection. The osteotomies of the quadrangular variant share characteristics of both Le Fort I and Le Fort II patterns and do not represent a classic Le Fort II. The anterior Le Fort II includes an osteotomy through the palate at the level of the bicuspid, thus creating an alveolar gap with advancement.

As can be expected, access to the bony skeleton requires a combination of incisions. Access to the maxilla is standard via vestibular incisions. For access to the nasofrontal region and medial orbit, direct cutaneous incisions over the nasal bridge were previously used. The trap door inverted V-Y by Converse is one such example. Perhaps more aesthetic incisions in this area are now hidden in the eyelids via a medial upper blepharoplasty incision or lower transconjunctival approach. Wedgewood describes an approach in which rhinoplasty incisions (transfixion, intercartilaginous) are combined with the intraoral incision to expose all osteotomy sites with a similar goal of minimizing cutaneous scarring. For broad access, a bicoronal may be combined with the intraoral incision, although it arguably carries significantly greater morbidity.

Indications

Le Fort III osteotomy

Skeletal facial deformities can be repetitive patterns of deformity affecting the different functional and aesthetic subunits of the facial hard and soft tissues. Their only common feature is the degree of variable expressivity within each subtype of anomaly. Although numerous procedures exist for the management of the various craniofacial malformations in the middle third of the facial skeleton, only the subcranial Le Fort III osteotomy addresses the nose, orbits, cheeks, and maxilla. However, specific limitations apply to the use of this surgical maneuver. The bony structures of the middle facial third are in contiguity with the cranial base superiorly. Transgression of this natural barrier is indicated in the surgical correction of some craniofacial anomalies, if the presenting deformity includes excessive interorbital distance or there is significant aberration of the supraorbital/forehead subunit. In these instances, consideration should be given to using a combined intracranial and extracranial approach, such as facial bipartition or monobloc osteotomy. In addition, subcranial Le Fort III osteotomy does not address the 3-dimensional vertical slanting of the facial halves or the convex arc of rotation of the face as seen in some of patients with craniofacial dysostosis, which can only be adequately managed with facial bipartition osteotomy.

This is not to suggest that within the context of an extracranial procedure the Le Fort III osteotomy is inflexible, rather the opposite is true. Modifications of the Le Fort III osteotomy, such as Kufner operation (modified Le Fort III), are possible and can be used to address deformities that do not involve the nasal subunit ( Fig. 2 ). Stability of these procedures in both syndromic and nonsyndromic patients has been studied. Thoughtful consideration by the surgeon must be given to addressing the presenting dysmorphology, with the intention of improving the aesthetic and functional concerns of the patient, while taking into account the potential complications and benefits inherent with the use of an intracranial approach. Management of the skeletally immature patient requires surgical intervention based on the complex balance between the long-term stability of the correction and more immediate functional, psychological, and aesthetic demands of each patient. As with all facial reconstructive procedures, patient selection is critical to successful outcome.

Craniofacial dysostosis

The craniofacial dysostosis syndromes (eg, Apert, Crouzon, Pfeiffer, Saethre-Chotzen, and Carpenter) are characterized by sutural involvement that not only includes the cranial vault but also extends into the skull base and midfacial skeletal structures. Although the cranial vault and cranial base are thought to be the regions of primary involvement, there is also significant impact on midfacial growth and development. In addition to cranial vault dysmorphology, patients with these inherited conditions exhibit a characteristic “total midface” deficiency that must be addressed as part of the staged reconstructive approach. Although there is some similarity between the pattern of facial growth and development in these patients, there is a high degree of variable expressivity seen in each patient regardless of syndrome. This must be taken into account when planning and executing surgical correction of these deformities. If the nasal subunit is normal or excessive preoperatively, further advancement of the nose will lead to a less than aesthetic result. Therefore, the surgeon must give consideration to subtotal midface advancement via modified Le Fort III osteotomy or consider a quadrangular Le Fort II osteotomy in this situation.

Midface deficiency

The role of the human face is significant in a both direct and indirect fashion for reasons other than purely aesthetic considerations. This is secondary to the highly evolved and specialized functions of the face in vision, breathing, speech production, smell, and hearing, among a few. Total midface deficiency, to include the orbits, nose, zygomas, and maxilla, can occur in both syndromic and nonsyndromic individuals. In patients with syndromal craniofacial dysostosis, in addition to potential neurologic deficits, there is often variable fusion of the lesser sutures of the skull base. This commonly results in abnormal ophthalmologic findings, including exorbitism, exotropia, orbital dystopia, and ptosis secondary to lack of orbital depth and diameter, as well as prolapse of the ethmoid sinuses through the medial orbital walls. The severe occlusal discrepancies found in this group of patients is characterized by generalized hypoplasia of the maxilla, transverse deficiency, class III malocclusion, and apertognathia. All of these abnormalities contribute to impact speech articulation errors and mastication. In addition, cleft palate, when present, can produce velopharyngeal incompetence. The severe retrusive position of the midface also can interfere with nasal breathing and produce chronic nasal obstruction. Varying degrees of orbital hypertelorism (OHT) may or may not be present. The extent to which this is present strongly influences the type of surgical correction required for midface deficiency.

The presence of midface deficiency does not mitigate the coexistence of other facial skeletal abnormalities, such as mandibular excess and retrogenia. In addition, there are often irregularities of the forehead, as well as frontal bossing. The nasal length can be short and projection may be deficient. However, there are many circumstances in which nasal projection is normal or even excessive, which then mandates subtotal midface advancement. Deficiency in orbital depth and diameter produces exorbitism and an excessive amount of sclera may be present. Ptosis of the lids and lateral canthal dystopia are usually present. When high levels of midface deficiency exist, the subcranial Le Fort III osteotomy or a modification thereof should be considered.

Le Fort II osteotomy

The Le Fort II osteotomy may be used to address the same population of patients as described previously, but perhaps with a focus on those patients with a more pronounced hypoplastic nasomaxilla. That is, the nose and maxilla are the components addressed surgically, rather than nose, maxilla, orbits, and cheeks all at once, as with the Le Fort III.

Patients with lateral nasomaxillary deviation (for instance in unilateral coronal synostosis, hemifacial microsomia, or Romberg disease) benefit from asymmetric osteotomies with movement in multiple vectors. Advancement addresses retrusion, whereas lateral pendulum type movement helps correct occlusal canting. Rotation about a vertical axis also aids in correcting deformities. These patients have greater malar deficiency on the side to which the nose is rotated, thus osteotomies on this side are lateral to infraorbital foramen. The osteotomy on the contralateral side is medial to the infraorbital foramen. When the mobilized nasomaxilla is rotated to the contralateral side, this increases the bulk of the deficient side while simultaneously minimizing decreases in bulk of the cheek on the contralateral side.

For the patient with a retruded noncleft hypoplastic nasomaxilla, bilateral osteotomies medial to the infraorbital foramen allow advancement to address the deficient areas.

It is important to note that a spectrum of anomalies occurs, and most patients have varying degrees of nasomaxillary hypoplasia, combined with orbital and malar retrusion. These patients may thus benefit from a combination of approaches with differential movement of various components (usually greater movement of the central midface), possibly in unison with distraction. For instance, monobloc advancement of the forehead and orbits may be combined with the Le Fort II osteotomy, to address deficiencies in each area. Similarly, zygomatic repositioning may be combined with the Le Fort II osteotomy. The central midface may be then be moved differentially, such as with advancement, vertical elongation, or sagittal rotation as necessary, while allowing appropriate movements of the forehead, orbits, or zygomas. This results in improvement of not only frontal views, but also birds and worms views.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses