Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

The latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap was the first musculocutaneous flap described in the medical literature. Initially it was reported by Tansini in 1896 as a modality for reconstruction after a mastectomy. He advocated excision of the skin in the mammary region to reduce the risk of cutaneous recurrences after breast cancer, and he detailed the transfer of the adjacent latissimus dorsi flap to reconstruct the defect. He further described his anatomic findings on the importance of axial circulation to such flaps, including the presence of perforators in myocutaneous flaps and the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous unit. In 1912, D’Este further developed this technique for breast reconstruction. It was not until decades later, however, that use of the latissimus dorsi flap was expanded, due to its numerous advantages, to encompass indications for shoulder and upper extremity defects. The first documented use of this flap for head and neck reconstruction was described by Quillen and colleagues in 1978. The pedicled latissimus dorsi flap, based on the thoracodorsal vasculature, was tunneled under the subcutaneous tissue and superficial to the pectoralis major, serving as an island rotational flap to reconstruct lateral neck and cheek defects resulting from the resection of a mandibular carcinoma with skin involvement.

Use of the latissimus dorsi flap as a free flap in the head and neck region was first reported by Watson et al. in 1979. The free flap was used to reconstruct a deep posterior neck dehiscence after excision of a large mass and also to correct a large defect subsequent to hemifacial microsomia with partial absence of the mandible and malar and temporal bones. Further modification of the latissimus dorsi flap technique introduced motor innervation of a reconstructed tongue by anastomosis of the thoracodorsal nerve to the hypoglossal nerve, in addition to reanimation of hemifacial paralysis with anastomosis to the facial nerve. Osseous reconstruction of the mandible and scalp with the inclusion of a rib for a osteomyocutaneous flap was reported by Maruyama and Hirase, respectively; however, this technique has not gained favor because of the advent of more suitable osteomyocutaneous free flaps, particularly for reconstruction of the maxillofacial region.

History of the Procedure

The latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap was the first musculocutaneous flap described in the medical literature. Initially it was reported by Tansini in 1896 as a modality for reconstruction after a mastectomy. He advocated excision of the skin in the mammary region to reduce the risk of cutaneous recurrences after breast cancer, and he detailed the transfer of the adjacent latissimus dorsi flap to reconstruct the defect. He further described his anatomic findings on the importance of axial circulation to such flaps, including the presence of perforators in myocutaneous flaps and the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous unit. In 1912, D’Este further developed this technique for breast reconstruction. It was not until decades later, however, that use of the latissimus dorsi flap was expanded, due to its numerous advantages, to encompass indications for shoulder and upper extremity defects. The first documented use of this flap for head and neck reconstruction was described by Quillen and colleagues in 1978. The pedicled latissimus dorsi flap, based on the thoracodorsal vasculature, was tunneled under the subcutaneous tissue and superficial to the pectoralis major, serving as an island rotational flap to reconstruct lateral neck and cheek defects resulting from the resection of a mandibular carcinoma with skin involvement.

Use of the latissimus dorsi flap as a free flap in the head and neck region was first reported by Watson et al. in 1979. The free flap was used to reconstruct a deep posterior neck dehiscence after excision of a large mass and also to correct a large defect subsequent to hemifacial microsomia with partial absence of the mandible and malar and temporal bones. Further modification of the latissimus dorsi flap technique introduced motor innervation of a reconstructed tongue by anastomosis of the thoracodorsal nerve to the hypoglossal nerve, in addition to reanimation of hemifacial paralysis with anastomosis to the facial nerve. Osseous reconstruction of the mandible and scalp with the inclusion of a rib for a osteomyocutaneous flap was reported by Maruyama and Hirase, respectively; however, this technique has not gained favor because of the advent of more suitable osteomyocutaneous free flaps, particularly for reconstruction of the maxillofacial region.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

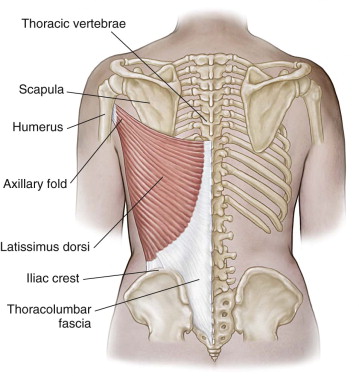

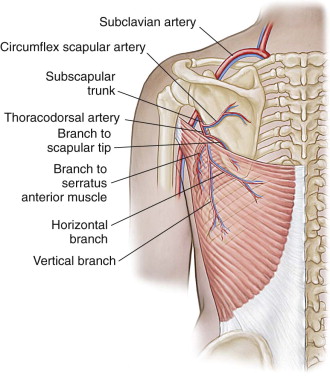

The substantial versatility and safety of the latissimus dorsi flap are due partly to the ease of flap raising, the high-caliber and excellent length of the vessels, a consistent vascular anatomy, ample available donor tissue, minimal donor site morbidity, and the high density of myocutaneous perforators to the skin paddle. The total area covered by each latissimus dorsi muscle is 25 to 40 cm, which provides a large source of robust tissue for defect closure ( Figure 113-1 ). The neurovascular anatomy has been well established; the thoracodorsal artery and vein arise off the subscapular vessels, which are located in the third part of the axillary artery. The thoracodorsal artery has major branches to the serratus anterior, teres major, latissimus dorsi, and tip of the scapula ( Figure 113-2 ). The ability of this flap to function as either a pedicled flap or a free microvascular tissue transfer adds to its versatility as a major musculocutaneous flap.

As a pedicled flap, the latissimus dorsi flap can be used in a number of reconstructions of the head and neck by passing it through the axilla and between the pectoralis minor and major muscles. Possible applications include mucosal defects of the pharynx and oral cavity; resurfacing of large defects of the face and neck, scalp, and temporal or occipital regions; and also orbital, maxillary, palatal, and midface cutaneous defects. Augmenting the arc of rotation of the pedicled flap facilitates its use in some of the more distant sites. Limitations of the arc of rotation are due to attachment of the thoracodorsal pedicle to major branches, such as the serratus anterior branches, which cause tethering of the inferior thoracodorsal pedicle. A greater arc of rotation can be gained by mobilizing the thoracodorsal pedicle off the circumflex scapular artery (CSA); however, caution must be used with this maneuver because this superior tethering to the CSA keeps the thoracodorsal pedicle from kinking when used as a pedicled flap. Fashioning the skin paddle over the most distal angiosome can permit reach of the flap for scalp and forehead reconstruction; however, the density of perforators in this area is much reduced, leading to a potential for loss of distal skin viability. Nevertheless, the advent of microvascular tissue transfer has enabled the use of this robust flap throughout the head and neck without major concern.

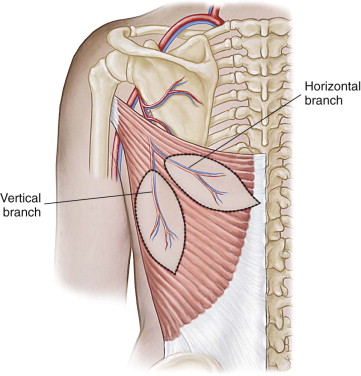

Through-and-through soft tissue defects of the oral and maxillofacial region involving both skin and mucosa can be reconstructed with the latissimus dorsi flap by folding over the skin paddle and de-epithelializing the intervening skin bridge ( Figure 113-3 ). Another technique for reconstructing these multiunit defects involves the creation of two skin paddles on the vertical and descending branches of the thoracodorsal pedicle, as described by Tobin et al. ( Figure 113-4 ). However, caution must be exercised when this flap is used due to its bulkiness, particularly when folded; the need for a secondary debulking procedure is not uncommon.

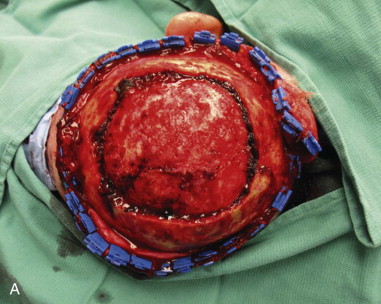

The free-flap form of the latissimus dorsi flap has many applications in the maxillofacial region. Its use for closure of large orbitomaxillary defects has been advocated, especially when significant bulk is needed to obliterate a defect after orbital exenteration. Two-pedicle techniques similar to those described previously have been used to close palatal and midface defects. Defects of the temporal and occipital scalp region can be reconstructed with either a pedicled or a free flap; however, if the defect is very large or includes the vertex of the scalp, a free flap typically is required. A common technique for large scalp defects involves the harvesting of muscle only, with primary skin grafting over the muscle flap ( Figure 113-5 ). This technique eliminates the need for primary closure of the donor site, allows the muscle to be stretched easily over the convex skull, and achieves closure to all points over the cranium.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses