Infiltration is preferred to regional block techniques in the maxilla as the former offers a number of advantages. This paper considers the evidence for the efficacy of infiltration anesthesia in the mandible in the adult dentition, both as a primary and as a supplemental method.

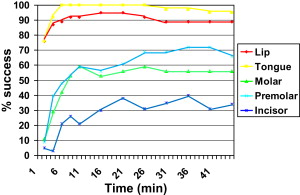

The gold-standard method of anesthetizing teeth in the lower jaw is by one of the regional block techniques, such as the Halstead, Gow-Gates, or Akinosi methods. An alternative is the mental and incisive nerve block. Regional blocks have several potential disadvantages when compared with infiltration anesthesia. The advantages of infiltration anesthesia are listed in Box 1 . In addition, the complications of local anesthesia, such as intravascular injection and nerve damage, are principally associated with regional block techniques. This association is not surprising because blood vessels are more likely to be associated with nerve trunks and deeper injections. Similarly, nerve trunks are more often damaged either by physical or chemical agents during regional block techniques. Another factor to consider is the finding that injections, such as inferior alveolar nerve blocks, are not equally successful for all teeth. The most susceptible are the premolars followed by the molars and then the mandibular anterior teeth ( Fig. 1 ). This susceptibility may be the result of an inability to counter collateral nerve supply, as may happen in the midline where structures receive bilateral nerve supply.

- •

Technically simple

- •

More comfortable for patients

- •

Provides hemostasis where it is needed

- •

Counters collateral supply in many cases

- •

Avoids damage to nerve trunks

- •

Less chance of intravascular injection

- •

Safer in patients with bleeding diatheses

- •

Reduced chances of needle stick injury

- •

Preinjection topical masks needle penetration discomfort

Of course, techniques, such as periodontal ligament (intraligamentary), intraosseous, and intrapulpal methods, may be used in the mandible; however, these are generally considered to be supplementary methods. These methods also have complications that are best avoided. Intraligamentary anesthesia produces damage to the tooth root, periodontium, and alveolar bone, although in the main these are reversible. It was previously mentioned that teeth vary in their susceptibility to inferior alveolar nerve blocks. A similar state of affairs exists with periodontal ligament anesthesia; lower incisor teeth are the most difficult to anesthetize with this method, probably as the result of few perforations in the cribriform plate of the dental socket in this region. This paucity of perforations inhibits the flow of solution from the periodontal ligament into the cancellous bone. Intraosseous anesthesia can cause systemic effects because this route is analogous to the intravenous delivery in relation to entry of local anesthetic and vasoconstrictor into the circulation. In addition, it is possible to produce physical damage to tooth roots during intraosseous anesthesia. Intrapulpal anesthesia has obvious limited indications.

Infiltration anesthesia

Infiltration anesthesia is the technique of choice in the upper jaw. It provides pulpal anesthesia by diffusion into the cancellous bone via the thin cortical plate of the maxillary alveolus. The thicker cortical plate of the mandible is considered to be a barrier to such diffusion in the lower jaw. Nevertheless a thick cortical plate is not always a barrier to local anesthetic diffusion. Evidence of this is the efficacy of the anterior middle superior alveolar (AMSA) technique in the palate where solution is deposited in the mucosa of the hard palate in the mid-premolar region halfway between the gingival margin and the midline. This technique can provide anesthesia of the pulps of the maxillary premolar, canine, and incisor teeth. The solution gains access to the cancellous space via perforations in the palatal bone. The mandibular cortex has perforations. The mandibular and mental foramina are obvious examples; however, other holes are present especially in the lingual aspect of the incisor region. Regional block techniques, such as the infraorbital and maxillary nerve blocks, can be used but infiltration is preferred in the maxilla because it is simple and effective. Thus it seems reasonable to assume that where both infiltration and regional blocks are effective the former is preferred. In addition to being a technically simple procedure, two major advantages that infiltration anesthesia provides are the countering of collateral supply and the provision of localized hemostasis.

Infiltration anesthesia in the mandible

Infiltration may be used in the mandible either to supplement other methods, such as regional block anesthesia, or as a primary technique.

Infiltration as a Supplementary Technique in the Mandible

Several studies have looked at the use of mandibular infiltration as a means of supplementing inferior alveolar nerve block injections. In an investigation of 331 subjects having regional block anesthesia in the mandible, Rood recorded 79 failures of pulpal anesthesia. This author used infiltration of 2% lidocaine with 1:80,000 epinephrine to overcome failure in these 79 individuals. A supplemental infiltration of 1.0 mL on the buccal aspect resulted in successful anesthesia in 70 of the 79 subjects. Seven of the other 9 subjects achieved successful anesthesia following further infiltration on the lingual aspect.

Haase and colleagues compared the effect of a supplemental infiltration of 1.8 mL of either 2% lidocaine or 4% articaine both with 1:100,000 epinephrine in the buccal sulcus in the mandibular first molar region on the efficacy of an inferior alveolar block with 4% articaine and 1:100,000 epinephrine. Using a double-blind, randomized crossover design these investigators reported that the articaine supplemental infiltration significantly increased anesthetic efficacy for the mandibular first molar compared with the lidocaine infiltration (88% vs 71% anesthetic success, respectively).

In a similar investigation, Kanaa and colleagues looked at the effect of a supplemental infiltration of 1.8 mL of 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine in the buccal sulcus in the mandibular first molar region on the success of an inferior alveolar nerve block of 2% lidocaine with 1:80,000 epinephrine in a randomized, double-blind crossover investigation. These investigators noted an increase in the incidence of pulpal anesthesia in mandibular teeth following the supplementary articaine infiltration compared with a dummy infiltration (needle penetration only) in the same region (92% and 56% anesthetic success for first molar anesthesia, respectively). In this last study the significant increase in efficacy was apparent not only in the first molar (where the infiltration was performed) but also in the first premolar and lateral incisor teeth. In the premolar teeth the supplementary articaine infiltration produced a success rate of 89% compared with 67% for the inferior alveolar nerve block alone; for the lateral incisor the success rates were 78% after the supplementary infiltration compared with 19% with the regional block alone. This finding demonstrates an effect on the nerve trunk within the inferior alveolar canal and not merely diffusion through to the apices of the first molar tooth. Whether this is the result of direct diffusion into the canal at the site of injection or spread along to the mental foramen and entry at that point is not possible to determine, but this is being investigated in another trial, unpublished at the time of writing.

Matthews and colleagues investigated the efficacy of a buccal infiltration of 1.8 mL of 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine in pulpitic teeth that had failed to succumb to an inferior alveolar nerve block. The supplemental injection allowed pain-free treatment in 57% of the subjects in whom the original block failed. The investigators state that this modest rate of success means that a buccal infiltration of 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine cannot be guaranteed to provide anesthesia in teeth with pulpitis.

Rosenberg and colleagues also looked at the use of supplementary buccal injections of either 4% articaine or 2% lidocaine (both with 1:100,000 epinephrine) to overcome failed inferior alveolar nerve blocks in subjects suffering from irreversible pulpitis. These investigators measured pain scores at various points throughout treatment and found no significant difference in the change in pain scores between the two supplemental solutions.

Similarly, Aggarwal and colleagues looked at the use of supplemental infiltrations to improve the efficacy of inferior alveolar nerve block injections in subjects with irreversible pulpitis. Inferior alveolar nerve block alone was successful in 33% of subjects; a supplemental buccal and lingual infiltration of 2% lidocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine increased success to 47%; and similar supplemental buccal and lingual infiltrations with 4% articaine containing 1:200,000 epinephrine was successful in 67% of cases, which was significantly better than the lidocaine infiltrations.

Fan and colleagues compared the intraligamentary injection of 0.4 mL of 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine with a buccal infiltration of the same dose of this solution as supplementary injections following an inferior alveolar nerve block in subjects suffering from irreversible pulpitis in the mandibular first molar. Both methods produced similar success rates (83% and 81%, respectively).

Infiltration as a Primary Technique in the Mandible

The use of infiltration anesthesia as a primary technique for anesthesia of the mandibular teeth has been investigated. Some studies have reported infiltration to be effective for many treatments in the mandibular deciduous dentition. The following discussion relates solely to the use of mandibular infiltration techniques for the permanent dentition in adults.

Incisor and canine region

It was previously mentioned that both regional block anesthesia and intraligamentary anesthesia were poor in providing anesthesia of the pulps of the mandibular incisor teeth. In this region the cortex is quite thin and might provide little resistance to infiltration. Three investigations have looked at the success of infiltration anesthesia for mandibular incisor teeth. Yonchak and colleagues compared the efficacies of 1.8 mL of 2% lidocaine with 1:50,000 or 1:100,000 epinephrine injected buccally to the lower lateral incisor for anesthesia of the ipsilateral canine and the lateral and central incisors. They noted no difference in anesthetic efficacy between solutions and recorded successes in the range of 47% to 53% for the canine, 43% to 45% for the lateral incisor, and 60% to 63% for the central incisor. In addition, these investigators looked at the success of injection of 1.8 mL of the 1:100,000 preparation lingually to the lower lateral incisor and recorded 11% success for the canine, 50% for the lateral, and 47% for the central incisor. Meechan and Ledvinka performed a similar investigation with 1.0 mL of 2% lidocaine containing 1:80,000 epinephrine and obtained 50% successful anesthesia of the mandibular central incisor when the local anesthetic was injected either buccally or lingually to the test tooth. In this last study, the success was increased to 92% when the dose of anesthetic was split between the buccal and lingual sides. A further randomized, double-blind crossover study comparing buccal versus buccal and lingual split dosing of 1.8 mL of 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine by Jaber and colleagues confirmed the finding that the latter technique improved the efficacy of anesthesia for the lower central incisor tooth. In this last study, which used a larger dose than that employed by Meechan and Ledvinka, the injection of 1.8 mL 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine provided successful anesthesia in 77% of volunteers after the buccal infiltration and 97% after the split buccal/lingual dose. This study also compared the use of 4% articaine to 2% lidocaine (both with 1:100,000 epinephrine) as an anesthetic for infiltration anesthesia in the anterior mandible. These investigators reported that 4% articaine was superior to 2% lidocaine in obtaining anesthesia of the pulps of the mandibular central incisor adjacent to the injection site and the contralateral lateral incisor following both buccal or buccal and lingual infiltrations. The success rate after articaine as a buccal injection was 94% at the lower central incisor and after the split buccal and lingual technique success for this tooth was 97%. For the contralateral lateral incisor the success rates with articaine were 61% as a buccal injection and 74% after the split buccal and lingual infiltrations compared with 36% and 42% with lidocaine.

Haas and colleagues compared the buccal infiltration of 4% articaine and 4% prilocaine for anesthesia of mandibular canine teeth and reported no significant difference in efficacy. The success rates these investigators noted were 65% for articaine and 50% for prilocaine.

Fig. 2 shows the efficacies of different methods of anesthesia for mandibular incisor teeth using no response to maximum stimulation from an analytical pulp tester as the criterion for success in similar populations. It can be seen from this graph that infiltration appears to be the method of choice for anesthesia of the mandibular incisors.

Molar region

Some of the studies previously cited suggested that the success of mandibular infiltration anesthesia was dependent upon the choice of anesthetic solution. Jaber and colleagues showed that 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine was more successful than 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine in obtaining pulpal anesthesia of mandibular incisor teeth after infiltration. Similarly, Haase and colleagues showed that 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine was more successful than 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 in supplementing an inferior alveolar nerve block for mandibular first molar anesthesia. In addition, the studies of Meechan and Ledvinka and Jaber and colleagues suggested that the splitting of a dose between buccal and lingual infiltrations was more effective than either buccal or lingual alone. The influence of different local anesthetic solutions and dose splitting for mandibular first molar anesthesia following infiltrations in the mandible has been investigated in several studies.

Kanaa and colleagues compared the infiltration of 1.8 mL of 2% lidocaine or 4% articaine (both with 1:100,000 epinephrine) for pulpal anesthesia of mandibular first molar teeth in a randomized, double-blind crossover volunteer study. These workers noted significantly greater efficacy for the articaine (64% success) compared with the lidocaine (39% success) solution. In an almost identical study, Robertson and colleagues reported similar findings, again noting superior efficacy with the more concentrated solution. These investigators noted anesthesia was successful in 87% of volunteers when 4% articaine was injected compared with 57% success with 2% lidocaine. Similarly, Abdulwahab and colleagues noted that 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine was more successful than 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine for pulpal anesthesia when infiltrated in the buccal sulcus in the mandibular first molar region. These last investigators reported success rates for first molar anesthesia of 39% with the articaine solution compared with 17% with lidocaine. Their success was lower than those of Kanaa and colleagues and Robertson and colleagues, probably because a smaller volume (0.9 mL) was used. It is not clear whether or not these results represent a greater inherent ability of articaine to diffuse through bone or simply reflect the use of a more concentrated anesthetic solution. It is apt, however, to point out that no significant differences were noted in the comparison of two different anesthetics (articaine and prilocaine) at the same concentration performed by Haas and colleagues.

Meechan and colleagues compared the effect of splitting a 1.8 mL dose of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine between buccal and lingual infiltrations to a buccal dose only and noted no difference in the incidence or pattern of pulpal anesthesia in mandibular first molar teeth (32% vs 39%, respectively). Similarly, Corbett and colleagues compared splitting a 1.8 mL dose of 4% articaine between buccal and lingual sides and found no benefit compared with the same dose injected on the buccal side only for pulpal anesthesia of mandibular first molars (68% vs 65% rates of successful anesthesia, respectively). Thus, contrary to the case with mandibular incisor anesthesia, there appears to be no benefit in splitting a dose between buccal and lingual sides in the mandibular first molar region. Whether or not that is the case for teeth more posteriorly positioned in the mandible, where the apices approximate the lingual side, has not been determined and is worthy of investigation.

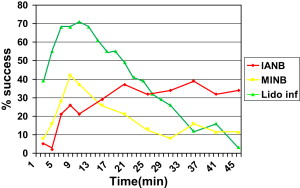

Comparisons of Infiltration and Regional Nerve Blocks

Two human, healthy-volunteer investigations have compared the efficacies of inferior alveolar nerve blocks to mandibular buccal infiltrations of 4% articaine with epinephrine for pulpal anesthesia of mandibular first molars. Jung and colleagues compared the buccal infiltration of 1.7 mL of 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine to an inferior alveolar nerve block with the same volume of the same solution and reported no significant difference in success between methods; success rates for first mandibular molars were 54% and 43%, respectively. These investigators noted that onset of anesthesia was quicker following the infiltration technique. Corbett and colleagues compared the infiltration of 1.8 mL of 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine to an inferior alveolar nerve block of 2.0 mL of 2% lidocaine with 1:80,000 epinephrine and, like Jung and colleagues, noted no difference in success between regimens (70% and 56%, respectively). These last investigators noted no significant difference in onset time of anesthesia between methods.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses