Infections in medically compromised patients

Publisher Summary

From a functional point of view, a compromised host is any patient, whose normal defense mechanisms are impaired, making the individual more susceptible to infection. There is a wide variety of conditions and illnesses that suppress normal defenses and allow infections to develop. These conditions might range from some of the more common entities, including damaged heart valves and diabetes, to immunodeficiency diseases, which are uncommonly encountered in the dental practice. Infections seen in compromised individuals are because of true exogenous pathogens, which also cause disease in non-compromised hosts. However, a significant proportion of infections in compromised patients is caused by endogenous and exogenous organisms with either a high or low degree of virulence and pathogenicity. These infections, referred to as opportunistic infections, are severe and might present to the clinician with atypical manifestations. This chapter focuses on the infection risks that are experienced by such patients; it discusses why it is important for dentists to have an understanding of the problems involved in their management.

Pathogenesis

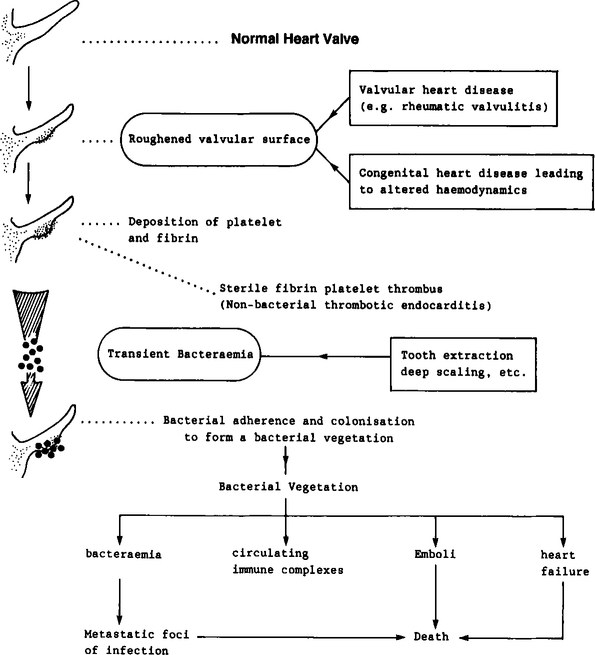

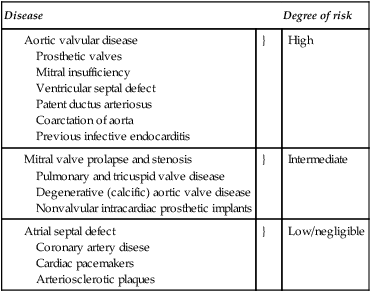

The development of infective endocarditis entails the sequential interaction of several events as shown in Figure 12.1. A breach of the integrity of the endocardium, or an abnormality of the endocardial surface per se, is the initial pathological event which makes the valvular surface eventually succumb to infection. Such a breach may occur due to the acute inflammatory valvulitis of rheumatic fever (consequential to Streptococcus pyogenes infection). In congenital heart diseases such as aortic valve disease and ventricular septal defect (Table 12.1) alterations of the blood flow patterns (haemodynamic turbulence) can result in a tendency for the deposition of fibrin and platelets at foci where high velocity jets of blood hit the valvular surface (Figure 12.1). These microscopic platelet aggregations may detach and emobolize harmlessly or stabilize and consolidate through fibrin deposition. The result is the formation of a thrombus at the site which is thus a potential trap for circulating microbes. Such sterile thrombus formation is sometimes referred to as non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis. This tendency towards platelet aggregation is not only limited to areas of damaged or denuded endocardium; platelets also have the potential to adhere to other ’foreign’ surfaces such as prosthetic valves. It is important to realize that non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis is usually asymptomatic, provided impaction of emboli in vital areas does not occur.

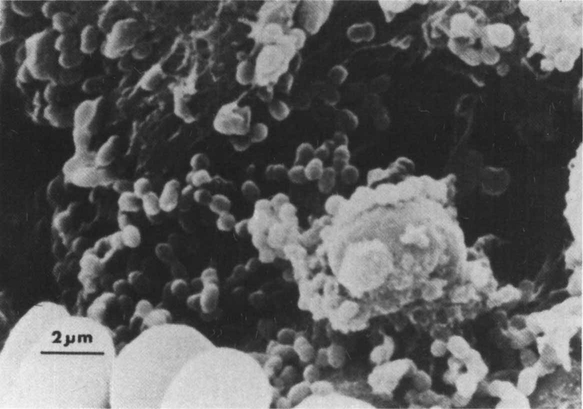

The next crucial event in the pathogenesis of the disease occurs when microorganisms circulating in the blood attach to or become trapped in the thrombotic endocardium or the prosthetic device. The resultant platelet–fibrin–bacterial mass, now called the bacterial vegetation, constitutes the primary pathology of infective endocarditis (Figure 12.2). Although the detailed mechanics of the microbial ecosystem of the vegetation is not clear, it is probable that once the organisms are attached to the lesion they multiply and colonize this niche in an exuberant manner. As a result, further aggregation of platelets and fibrin deposition would ensue, thus protecting the organisms from the body defences. The organisms now reside in a sanctuary inaccessible to phagocytes by virtue of the fibrin-platelet barrier. Further, the bacteria may be sheltered from antibiotics and host antibodies, as the vegetation is essentially avascular in nature. As a result, it is necessary to use an intensive course of prolonged, high-dose antibiotic therapy to eradicate such an infective focus.

A wide array of different bacterial species, fungi and chlamydiae can cause infective endocarditis. The most common causative organisms of endocarditis are shown in Table 12.2. More than 80% of infective endocarditis is caused by streptococci and staphylococci. The eminent position held by the Strep. viridans group of organisms in the league table (Table 12.2) indicates the major role played by the oral commensals in causing this life-threatening disease. Strep. viridans was responsible for about 90% of endocarditis cases some 50 years ago when most patients were young and rheumatic heart disease (related to Strep. pyogenes infection) was common. Although the patients seen today are older and the proportion of cases due to Strep. viridans (mainly Strep. sanguis) has fallen, this group of organisms is still the most frequent cause of endocarditis. It is noteworthy that nearly all patients with Strep. viridans endocarditis have a previous heart lesion and about a quarter give a history of a recent dental procedure as a precipitating factor.

Table 12.2

Causative microorganisms in infective endocarditis

| Microorganisms | Cases (%) |

| Total Streptococci | 60 |

| Streptococcus viridans | 35 |

| Streptococcus faecalis | 13 |

| Microaerophilic streptococci | 3 |

| Anaerobic streptococci | 2 |

| Others | 7 |

| Total Staphylococci | 25 |

| Staph. aureus | 20 |

| Staph. epidermidis | 5 |

| Miscellaneous | 5 |

| Culture negative | 10 |

(cumulative data from several sources)

Infective endocarditis prophylaxis

Since dental-related endocarditis may well be the most common potentially fatal complication of dental treatment, all practitioners must have a good working knowledge of the problem. There is good evidence that dentists know about endocarditis and its prevention. However, some of the prophylactic regimens which have been used in the past have been purely empirical and in recent years a more scientific approach has been used. Table 12.3 shows the key principles of prophylaxis.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses