Chapter 7

Group Practice

The focus of this chapter is the small to medium-sized group practice—8 to 20 physicians. Large ambulatory-care networks, such as Mayo or Cleveland Clinic or the 100,000- to 150,000-square-feet hospital-based ambulatory facilities that have become so common in the past 10 years on medical center campuses, are far too complex to cover in one chapter. These facilities grow out of a context of politics (relationships between physicians and hospitals as to what departments will be included and how the revenue is to be divided); an analysis of market share; and a sophisticated master planning process that involves workload analysis using computer programs to model various scenarios, analyze revenue stream, allocate space by department, and estimate construction cost. Nevertheless, this book will be helpful at the micro level, as each department is planned, since the basic composition of each specialty suite and the layout of typical rooms, as well as the equipment used, will be relevant. In addition, the many patient-centered features and design ideas will be useful. The reader is reminded to read Chapters 3 and 5 as background for Chapter 7. These include a discussion of digital technology. As a point of information, a good resource for a variety of statistics and information is MGMA, the Medical Group Management Association.a

The point of origin for all group practices is the Mayo Clinic. Founded in 1897, it became the prototype for others that followed, including the prominent Menninger Clinic in Topeka. The Mayo Clinic is reputed to be the world’s largest medical clinic. While few can attain this level of achievement, many of the principles upon which the Mayo Clinic was founded apply to smaller group practices as well. These include the sharing or pooling of knowledge, a division of labor that allows physicians to concentrate on their specialty, and a desire to stay on the cutting edge of new technology. It is a teamwork approach to the delivery of medicine. Now, many years later, with the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and patient-centered medical homes, a collaborative care model is gaining prominence across the nation.

There is an ever-increasing trend toward group practice. Economics and the threat of for-profit chains dominating the market have encouraged many solo practitioners to band together in groups to enhance their strength and presence. Moreover, group practice offers physicians more power when negotiating managed care contracts. Although some physicians do not feel psychologically geared to practice in a large organization, and some fear a loss of individual authority in medical matters, group practice does increase a physician’s productivity and may lower the cost of healthcare.

In theory, each physician can be made more productive by eliminating the waste and inefficiencies inherent in a solo practice. A solo practitioner may work a 60- or 70-hour week, but perhaps 20 percent of his or her time is spent on office management. A group practice provides a division of labor with sufficient personnel to perform these nonmedical tasks, thereby enabling physicians to concentrate solely on practicing medicine.

Another advantage of group practice is the convenience of having a fully staffed radiology department and clinical lab in the physician’s own office. Equipment that might be too costly or underutilized in the small medical office can easily be justified in a large group practice. Other benefits of a group practice are greater freedom with regard to leisure time. Partners can cover for one another with no lack of continuity in care for the patient. And physicians in a multispecialty group provide one another with immediate access to specialists in other fields. This pooling of resources provides patients more efficient and complete professional services than each physician could provide individually.

Of course, economics plays a prime role in motivating physicians to practice together. Eight physicians in private practice would require eight business offices, eight waiting rooms, possibly six to eight X-ray rooms, six to eight minor surgery rooms—a great duplication of space and personnel. Together, as a group, the eight might have two minor surgeries, two X-ray rooms, one large waiting room, and one centralized business office. More efficient use of space and personnel means more income for physicians and perhaps lower costs for patients. In addition, certain lab tests or X-rays that might otherwise be sent out could be done within a properly equipped suite, netting extra fees for the group practice to reduce office overhead, providing CLIA regulations are met. Refer to Chapter 3 for a discussion about why physicians currently do little lab work within their offices, and to the Introduction for information about HIPAA.

As healthcare approaches the status of a commodity, the pressure on group-practice physicians to meet revenue goals (with compensation often tied to productivity) has steadily increased. The big shift is from volume-based to value-based care, which is a new ball game. The group-practice model that once sheltered physicians from some of the minutiae of private practice has imposed its own sort of tyranny, which, as reimbursement steadily decreases, enslaves them to “beat the clock,” seeing ever greater numbers of patients and enjoying it less. In past years, the billing of ancillary services helped to compensate for declining professional fees as managed care continued to dominate the marketplace. However, CLIA regulations and the Stark statute (relates to physician self-referral regulations) have made it difficult to vertically integrate ancillary services to enhance physicians’ income without tripping over conflict-of-interest issues and ever more complex compliance requirements.

STARK STATUTE

Stark I

Named after California senator Pete Stark, this statute creates penalties for physicians who engage in self-referral of Medicare patients to clinical labs in which they have a financial interest. Known as Stark I, the legislation was enacted by Congress in 1989.

Stark II

Stark II, enacted by Congress in 1993, prohibits self-referrals for radiology, hospital inpatient/outpatient, and eight other services. Proposed regulations on Stark II, issued in 1998, were considered by many to be confusing and ambiguous, prompting the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA—now CMA) to issue important changes in the Stark II final rule as a response to formal hearings and criticism. The definition of group practice has been broadened in terms of what qualifies as a “single legal entity,” and productivity bonuses and profit-sharing rules have been revised. Significant changes were made to the “in-office ancillary services” exception to ownership and compensation arrangements. The final rule, divided into Phase I and Phase II, is reported in the January 4, 2001 Federal Register. Phase I became effective January 4, 2002.

Stark II, Phase III

On September 5, 2007, CMS completed the third installment of Stark which includes an in-office ancillary services exemption, meaning that group practices may have in-house, lab, radiology (except for CT, MRI, and PET), physical and occupational therapy and be able to bill for it without breaking Stark law. If the group has MRI, CT, or PET, it is obligated to post a sign where it is visible to tell patients the names of other local facilities available to them.

ACCREDITATION

At the start of programming, the space planner must determine the type of certification, accreditation, or licensing the group is seeking. Some regulatory agencies have requirements that affect space planning and design (Medicare certification, for example), while others deal with issues of governance, credentialing, quality management and improvement, and clinical records. Periodic onsite surveys and peer review occur. These agencies may include The Joint Commission, Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC), and a number of organizations that accredit managed care enterprises. Refer also to Chapters 5 and 8 for additional discussion of these issues.

TYPES OF GROUP PRACTICES

There are four types of group practices in terms of space-planning considerations. The single-specialty group consists of physicians (rarely more than eight) who are all of the same medical specialty. This type of group permits a physician a great deal of freedom since patients usually will accept treatment from any member of the group. This allows for better utilization of all the doctors’ time. The single-specialty group represents the majority of group practices and this includes family practice and internal medicine.

The multispecialty group might typically be a large clinic offering internal medicine, OB-GYN, urology, pediatrics, family practice, ENT, or any combination of medical specialties. A group such as this could potentially offer many of the outpatient services provided by a hospital: clinical lab studies, diagnostic radiology, physical therapy, chemotherapy infusion, endoscopy, and multiphasic medical screening. A multispecialty group might consist of 20 physicians to several hundred physicians, as in an HMO.

The internal medicine group might be a group of general internists plus those with various subspecialties: pulmonary medicine, cardiovascular disease, hematology, oncology, gastroenterology, or endocrinology. A large enough group could support its own clinical lab, radiology department, cardiovascular rehabilitation, and pulmonary function testing.

The family practice group enables primary care physicians to expand beyond their individual resources in purchasing equipment and staffing an office. Large family practice groups are often found in small towns, and sometimes they have one or more specialists on staff in an effort to offer the community a wider range of services.

Top Issues in Ambulatory Settings

| 1. Patient satisfaction issues | Coming and going:

|

| 2. Accommodating change | Adopting medical technology Adopting and integrating technology |

| 3. Place-centered issues | Entry, screening and waiting zones Diagnostic imaging Pre-op and operating rooms Exam rooms |

| 4. Operational efficiency issues | Workforce issues: Use of staff and human resources (with implications to the environment and the organization): Aging staff issues Labor shortages, such as increased workload, risks, stress Direct care worker satisfaction Communication among all direct care providers |

PRIMARY CARE CLINICS

The primary care clinic is an extension of the family practice group, which, depending on the extent of ancillary services, can be quite large and self-sustaining. As an example, some may be developed to contract with insurance companies or large employers to provide total care for patients on a capitated (fixed amount per month) basis. There is every incentive to keep patients out of the emergency room (ED) and out of the hospital, since that cost comes out of the medical group’s profit. Therefore, some clinics have an urgent care unit to observe and treat patients who might otherwise go to the ED. They also offer fairly extensive diagnostic imaging and lab services. Physicians in these clinics are salaried employees, a number of whom may have a financial interest in the enterprise.

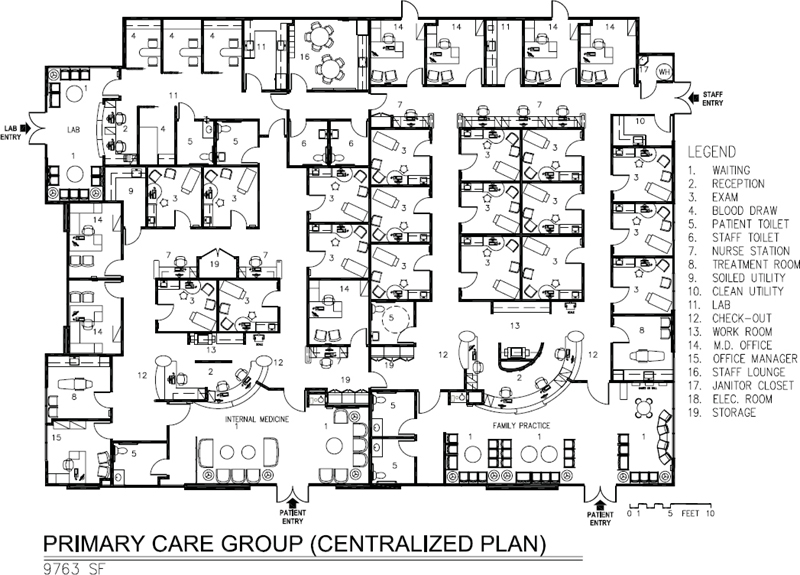

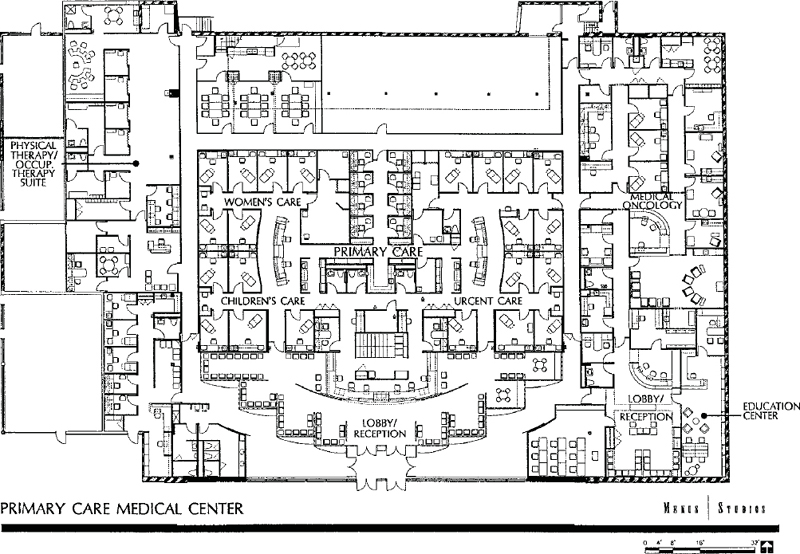

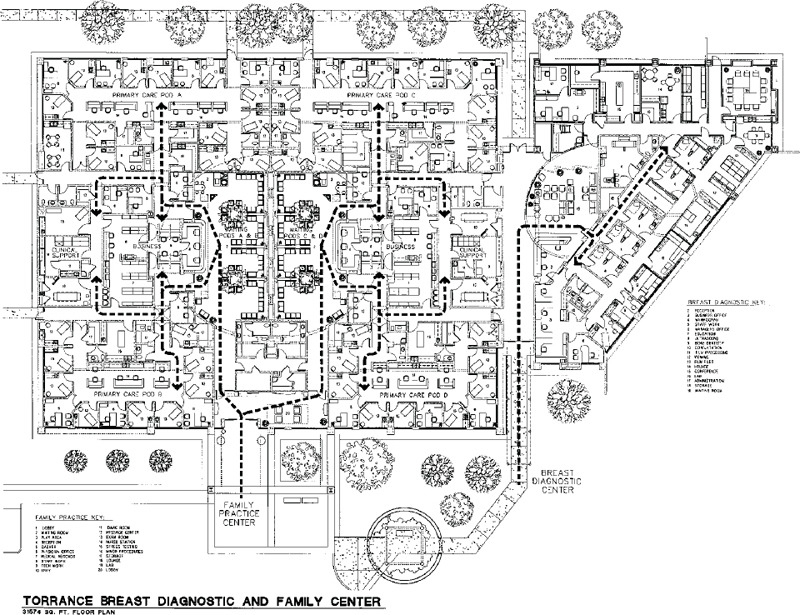

In Figure 3-43, registration, ancillary services, and urgent care are on the first floor with direct gurney access from urgent care to the exterior. X-ray is part of the urgent care center. The primary care facilities in Figures 7-1 and 7-2 are associated with a nearby hospital system, which means that they are designed to be feeders to the ancillary services of the main campus. Therefore, they do not have X-ray or cardiopulmonary testing onsite. Figure 7-2, on the Internal Medicine side, has a lab. These two facilities are located in single-story retail/office complexes with convenient parking. The hybrid nature of primary care clinics can be illustrated by Figures 7-3 and 7-4, which, in addition to the expected components, feature, respectively, a medical oncology unit and a diagnostic breast center. Figure 7-4 has X-ray onsite but Figure 7-3 does not, even though it has an urgent care center. It is likely that it is a feeder to the hospital’s ancillary services. This facility is an example of adaptive reuse; it was a 30-year-old former supermarket. (Author’s comment: Figures 7-3 and 7-4 were carried over from the third edition of this book because they have some good planning features although they predate electronic medical records, digital X-ray, and toilet rooms do not meet current ADA.)

Figure 7-1. Space plan of primary care group, 9,763 square feet.

Figure 7-2. Space plan of primary care group, 13,485 square feet.

Figure 7-3. Space plan of St. Francis Hospital Primary Care Medical Center, Morton Grove, Illionois, 30,000 square feet.

Figure 7-4. Space plan of Torrance Breast Diagnostic and Family Center, 31,574 square feet.

Centralized waiting and registration areas lead directly to four primary care pods and to diagnostic imaging in Figure 7-4, while the breast center has its own entry and well-appointed waiting room. The flow in this plan is excellent if the goal was to have four distinct primary care pods that don’t connect. More recently, with the focus on flexibility, it is likely it would have been planned with a connecting corridor to enable staff to flow “seamlessly” from one pod to another, although this would have resulted in the loss of one exam room in each pod and would interrupt the centralized core services. The symmetry of this layout is appealing and is often difficult to achieve.

HEALTH MAINTENANCE ORGANIZATIONS

In theory, any of these groups can be organized as a health maintenance organization although, since the obligation of an HMO is to provide a full range of health services to its members, it would most likely be only the large multispecialty group that would be prepared to do this. Kaiser is the best-known HMO of this type. More commonly, HMOs contract with medical group practices, individual physicians, and other healthcare providers to provide services for their members who prepay a monthly fee in addition to a fee or copay at the time the service is rendered. For many individuals, this arrangement centralizes and simplifies their healthcare and eliminates debates with insurance companies over what is covered and not covered, and it eliminates the need to individually pay a number of physicians. Members may be issued an embossed identification card that is presented to the receptionist upon checking into the clinic or may enter a PIN number into a kiosk computer. Some healthcare organizations use an electronic handprint for identification. The identification card or PIN has the patient’s billing code and other pertinent information coded into it. Thus, although an HMO may have more members than a similar-sized multispecialty group that charges a fee for service, billing procedures are often less complicated (there are no insurance claims to file) and are facilitated by sophisticated data-processing software.

Large multispecialty group HMOs like Kaiser have historically stressed health maintenance on the basis that it is less costly to keep people healthy than to treat them when they are sick. An HMO that follows this principle should be designed to accommodate many more patients than would a multispecialty group of the same number of physicians, and many more physician extenders may be employed in an HMO to provide health screening and other procedures aimed at preventive medicine. The ACA is changing all this, however, in new mandates for primary care that focus on value and continuity of care whether in an HMO setting or otherwise, and the use of physician extenders will also increase to be able to accommodate more patients and do more than episodic care. Having said that, the HMO of today differs from the somewhat idealistic model of yesteryear—one that promised to keep people healthy. Spending money to keep enrollees healthy only pays off if members stay with the plan a number of years. If they switch plans, the new HMO realizes the benefit. This has forced many HMOs to make tough decisions about how much they can offer at a capitated rate.

An HMO based on the staff or Kaiser captive group model will usually have a large physical therapy department, chemotherapy, cardiopulmonary lab, and allergy department—all of which may process a large volume of patients daily who do not usually have to see a doctor.

HMO MODELS

The four types of HMOs are the independent practice association (IPA), the group model, the network model, and the staff model. Current 2013 numbers are not readily available but in 2002, as mentioned in the former edition of this book, the IPA represented 58 percent of all HMOs, followed by group models with 23 percent, and network models with 12 percent. Staff and captive group models, together, total approximately 7 percent of the market. In all but the staff model, the HMO contracts with medical groups or individual physicians to provide care to its enrollees and, in turn, contracts with employers to provide services to their employees. In addition, HMOs enroll individual members and families. Following is a description of the various HMO models.

Independent Practice Association

In this model, the HMO either develops or contracts with an existing association of individual physician practices to provide services to enrollees. Physicians are paid on a negotiated fee-for-service basis or on a per capita basis, called “capitation.” IPAs allow physicians to remain in private practice and to treat subscribers in their own offices. Patients select from a list of providers, which includes hospitals, physicians, physical therapists, and others, to meet their healthcare needs. An HMO may employ a “gatekeeper” system that requires patients to select a primary care physician, who makes referrals to specialists, although some HMOs permit patients to self-refer to a specialist.

Network Model

The HMO, in this model type, contracts with several multispecialty group practices to provide services to enrollees residing in a single large service area or several noncontiguous service areas, with physicians commonly reimbursed on a per capita basis. Medical groups may also provide services to non-HMO patients.

Group Model

The group model has two forms: the captive group, in which the HMO itself forms the group, usually a large multispecialty group (Kaiser is the most well-known example of this) and the independent

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses