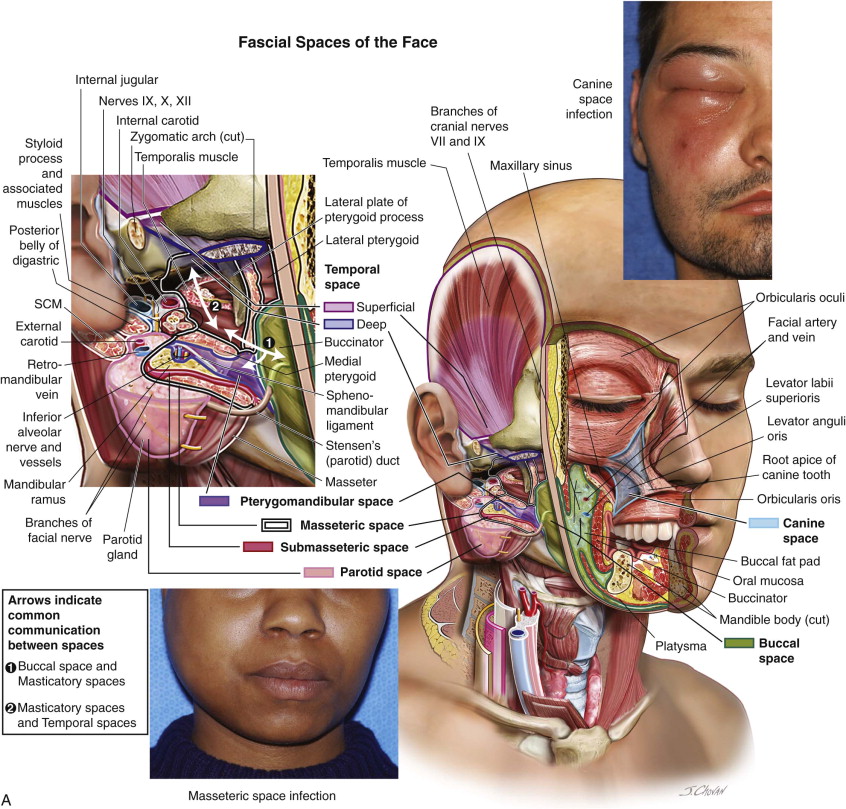

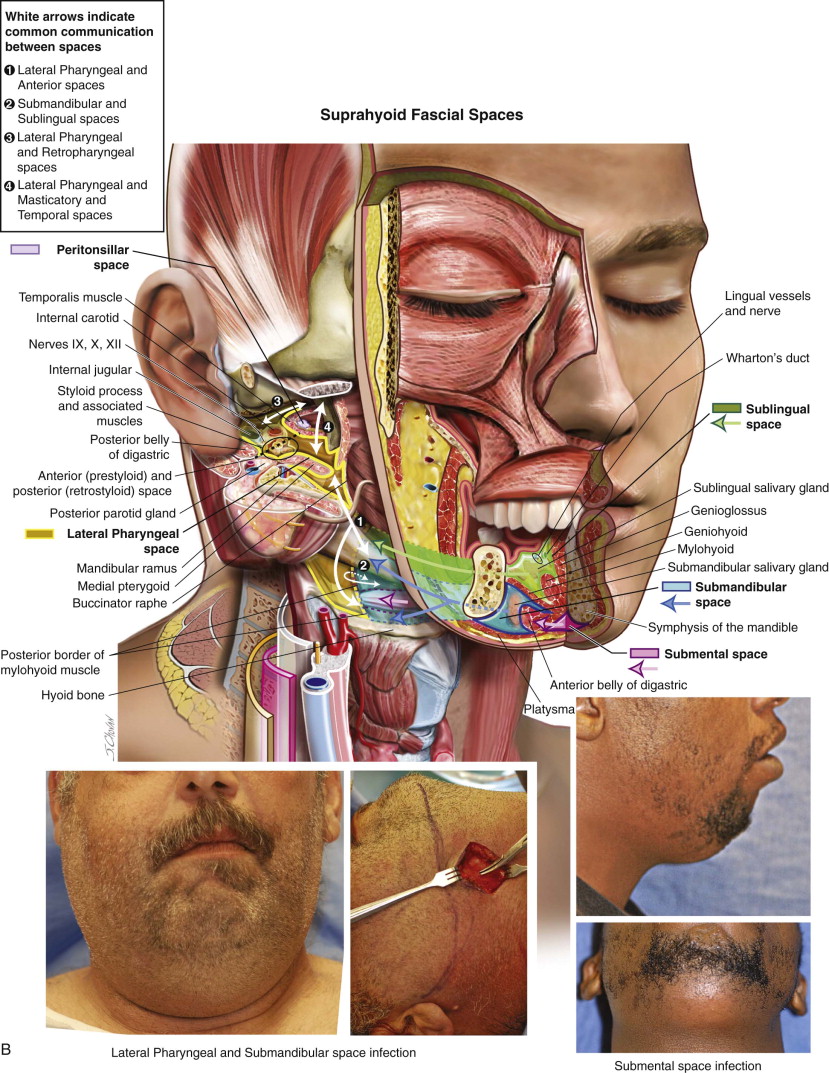

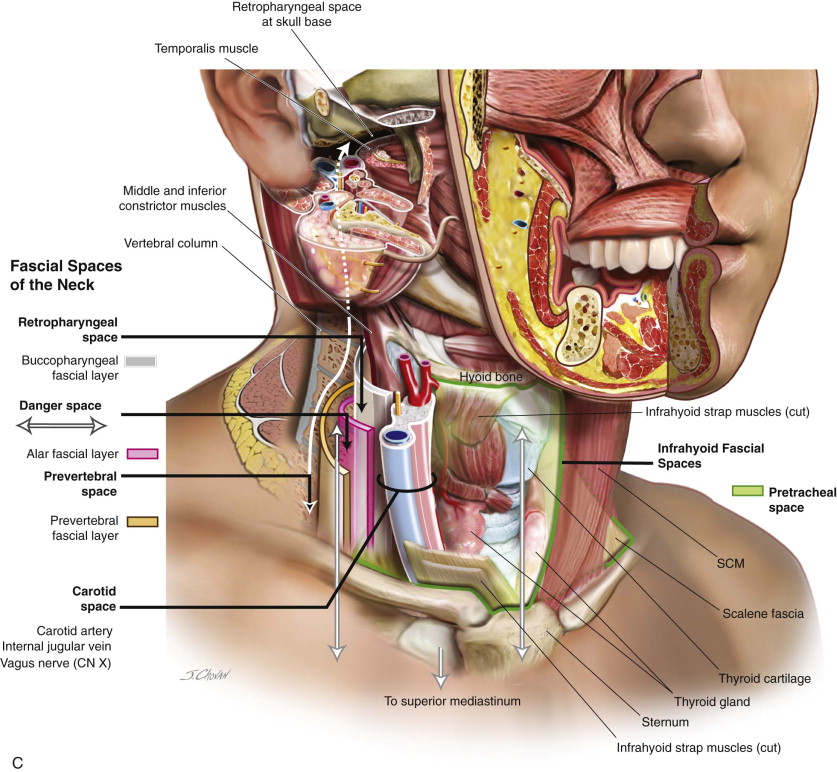

The fascia of the head and neck is composed of loose fibrous connective tissue envelopes and may be divided into the superficial and deep fascia. Between the fibers of the matrix are interstices that are filled with tissue fluid or ground substance that can readily break down when invaded by infection. The loose fibrous connective tissue that makes up the fascia of the head and neck is found in varying degrees of density with a tensile strength somewhat less than dense fibrous connective tissue located elsewhere in the body. There are 16 fascial spaces of the head and neck region divided into four subtypes. These four subtypes are the fascial spaces of the face, suprahyoid fascial spaces, infrahyoid fascial spaces, and the fascial spaces of the neck.

| Fascial Space Subtype | Fascial Space Subtype Components |

|---|---|

| Fascial spaces of the face |

|

| Suprahyoid fascial spaces | Sublingual, submental, submandibular, lateral pharyngeal, peritonsillar |

| Infrahyoid fascial spaces | Pretracheal |

| Fascial spaces of the neck | Retropharyngeal, danger, carotid sheath |

Superficial Fascia

The superficial fascia of the head and neck lies just under the skin, as it does in the entire body, invests the superficially situated mimetic muscles (platysma, orbicularis oculi, and zygomaticus major and minor), and is located in distinct anatomic areas. It is composed of two layers, an outer fatty ( areolar cleavage plane) layer and a thin inner membrane with a large number of elastic fibers ( superficial musculoaponeurotic system [SMAS] ). The superficial fascia attaches the skin to the deep fascia, which covers and invests the structures lying deep to the skin while maintaining the movability of the skin, with the two layers allowing for separation during blunt dissection. The areolar cleavage plane overlies the lower masseter, is rhomboidal in shape, and is important in cosmetic surgery (such as lower [cervicofacial] facelifts), because dissection is bloodless and provides safety for all facial nerve branches, as they are located outside this plane.

The SMAS is a fibromuscular fanlike fascial extension of the platysma muscle that arises superiorly from the fascia over the zygomatic arch. The facial nerve lies deep to the SMAS and innervates the mimetic muscles of the forehead and midface from the ventral aspect of the muscles. The SMAS is continuous with the platysma muscle inferiorly and the superficial temporal fascia superiorly, superficial to the parotideomasseteric fascia, and it connects to the fascial musculature in the nasolabial, perioral, and periorbital regions. Location and anatomic identification of this layer are important in surgical manipulation for both reconstructive and cosmetic procedures.

Deep Fascia

The deep fascia begins at the anterior border of the masseter muscle, attaches to the superior temporal and nuchal lines, and posterior and inferior to these margins it continues cranially as the pericranium. The deep facial fascia represents a continuation of the deep cervical fascia cephalad into the face and, more posterior, invests the muscles of mastication, the surgical importance of which lies in the fact that the facial nerve branches within the cheek lie deep to this fascial layer.

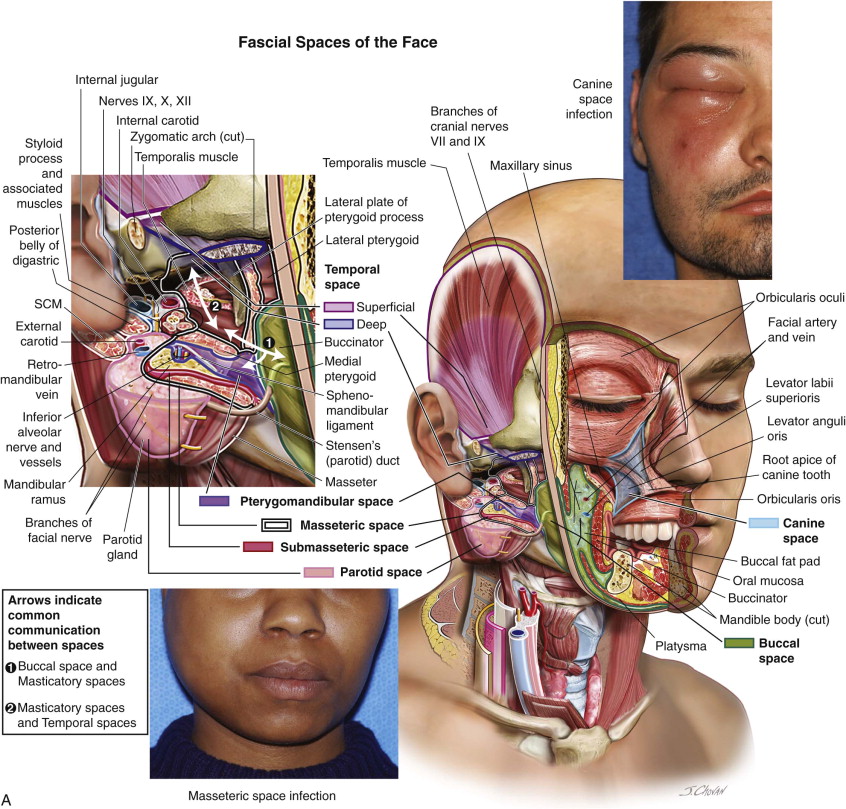

Fascial Spaces of the Face

The fascial spaces of the face are subdivided into five spaces: the canine space, the buccal space, the masticatory space (further divided into the masseteric, pterygomandibular, and temporal spaces), the parotid space, and the infratemporal space ( Figure 8-1, A ).

Canine Space

The canine space is located between the levator anguli oris and the levator labii superioris muscles. Infection spreads to this space through the root apices of the maxillary teeth, usually the canine. Direct surgical access is achieved through incision through the maxillary vestibular mucosa above the mucogingival junction ( Figure 8-1, B ).

Buccal Space

The buccal space is bounded anterior to the masticatory space and lateral to the buccinator muscle, with no true superior or inferior boundary, and consists of adipose tissue (the buccal fat pad that fills the greater part of the space), Stensen’s duct, the facial artery and vein, lymphatic vessels, minor salivary glands, and branches of cranial nerves VII and IX. The buccal space frequently communicates posteriorly with the masticatory space because the parotideomasseteric fascia is sometimes incomplete along its medial course where it joins the buccopharyngeal fascia. The parotid duct separates the buccal space into two equal-sized anterior and posterior compartments, with the facial vein located along the lateral margin of the buccinator muscle just anterior to transversely coursing Stensen’s duct.

The buccal space may serve as a conduit as there is a lack of fascial compartmentalization in the superior, inferior, and posterior directions, which permits the spread of pathology both to and from the buccal space. Surgical access to the buccal space infections may be easily accomplished through the intraoral approach. However, more complicated infections or masses, directed by location within the buccal space and suspicion of malignancy, may require a preauricular or submandibular approach.

Parotid Space

The parotid space is formed by splitting fascia of the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia and contains the parotid gland with associated extraglandular and intraglandular lymph gland, the parotid portion of cranial nerve VII, the external carotid, internal maxillary, and superficial temporal arteries, and the retromandibular vein. Infection in this space may spread to the lateral pharyngeal spaces, as they communicate posteriorly and the fascia of the deep parotid space is thin and easily breached. However, primary infection in this is rare and is generally blood-borne or retrograde through the parotid duct.

Masticatory Spaces

Masseteric Space (and Submasseteric Space)

The fascia that forms the borders of the masseteric space is a well-defined fibrous tissue that surrounds the muscles of mastication and contains the internal maxillary artery and the inferior alveolar nerve. It is bounded anteriorly by the mandible, posteriorly by the parotid gland, medially by the lateral pharyngeal space, and superiorly by the temporal space.

Most masseteric space infections are of odontogenic origin (e.g., molar teeth), with trismus being the most pronounced clinical feature, and often preclude intraoral examination. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be an invaluable resource in the assessment of masseteric space infections, as it can often influence the surgical approach and distinguish abscess from cellulitis. The submasseteric space is bounded laterally by the masseter muscle, medially by the mandible ramus, and posteriorly by the parotid gland. Infections are mostly of odontogenic origin (usually a mandibular third molar) and are often misdiagnosed as a parotid abscesses or parotitis. Intraoral surgical access to this space for simple, isolated abscesses is generally adequate to allow for drainage, but with extension into adjacent spaces, an extraoral submandibular approach may be required ( Figure 8-1, C ).

Pterygomandibular Space

The pterygomandibular space is bounded by the mandible laterally and medially and inferiorly by the medial pterygoid muscle. The posterior border is formed by the parotid gland as it curves medially around the posterior mandibular ramus and anteriorly by the pterygomandibular raphe, the fibrous junction of the buccinator and superior constrictor muscles. The inferior alveolar and lingual nerves, other structures in this space, are of particular importance in the administration of local anesthesia, including the inferior alveolar vessels, the sphenomandibular ligament, and the interpterygoid fascia. Surgical access to this space may be achieved intraorally in the case of simple infections, but may require extraoral access when multiple adjacent spaces are involved.

Temporal Space

The temporal fascia surrounds the temporalis muscle in a strong fibrous sheet that is divided into clearly distinguishable superficial and deep layers that originate from the same region with the muscle fibers of the two layers intermingled in the superior part of the muscle. It attaches to the superior temporal line and passes inferiorly to the zygomatic arch. Superiorly, the temporal fascia and fibers of origin of the temporalis muscle blend into a firm aponeurosis, a flat fan of extremely dense and firm fibrous connective tissue. Communicating facial-zygomaticotemporal nerve branches piercing through the fascial and muscular planes of the intermingled superficial and deep layers of the temporal fascia in the superior part of the muscle are important from a surgical perspective to prevent temporal hollowing that may occur due to surgical access procedures.

Fascial Spaces of the Face

The fascial spaces of the face are subdivided into five spaces: the canine space, the buccal space, the masticatory space (further divided into the masseteric, pterygomandibular, and temporal spaces), the parotid space, and the infratemporal space ( Figure 8-1, A ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses