Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

The term “facelift” in current popular culture has come to describe any number of procedures that help rejuvenate the appearance of the lower face and neck and that may or may not involve an invasive surgical procedure. Early scientific descriptions of facelift surgery from the nineteenth century primarily dealt with single-plane elevation of the skin of the lower face and neck, posterior/superior pulling of excess tissue with excision of redundant skin, and closure. Skoog first described a deeper plane approach to tightening the neck by undermining the posterior platysma and repositioning in a posterior/superior location. Mitz and Peyronie described the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) in 1976, which allowed for a better understanding of how to safely proceed with deeper dissections in the midface without injuring the facial nerve. Biplanar lifts involving undermining of the skin and also the SMAS subsequently were advocated on grounds that a longer-lasting, more natural result could be obtained. Authors noted that the SMAS could be repositioned in one vector and the skin in a slightly different vector to sculpt the face. Liposuction typically was advocated as an adjunct to the procedure. With the advent of aggressive resurfacing techniques, such as the carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) laser and phenol peels, deep plane lifts were described in which subcutaneous skin dissection was minimized to allow simultaneous resurfacing. Lift was achieved solely through the undermining and repositioning of the SMAS layer. Hamra and others described modifications to allow elevation of the midface simultaneously with the facelift. Other authors described a simultaneous subperiosteal elevation in the midface and mandible to release the true retaining ligaments of the face and allow more passive repositioning. As techniques became more aggressive, recovery periods and the potential for serious complications increased.

Over the past 10 to 15 years, the trend in facelifts has been toward less invasive lifts. In many ways these facelifts resemble the lifts described in the 1970s, with less reliance on extensive subcutaneous dissection and some form of minimal modification of the SMAS. Adjunctive techniques involving additive volumizing, resurfacing, and selective liposuction are routinely performed along with the facelift so that one technique is no longer responsible for achieving the entire goal of the operation.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

As the history of the facelift suggests, the goal is to rejuvenate the lower face and neck through tightening of the superficial and deeper structures, with modification of fat planes as necessary.

Skin Laxity

General “looseness” of the skin of the face and neck is often the primary reason given by patients for seeking a facelift. It is important to evaluate the general thickness of the skin, its apparent elasticity and glandularity, and the presence of fine and coarse rhytids. The procedure is generally not successful at “pulling out” fine lines; these are best addressed with a resurfacing procedure, and the patient should be informed accordingly. Exceptionally thick or thin skin may be prone to relapse. Male patients classically have thicker skin that relapses in the neck region early (1 to 2 years) and may require a touch-up neck lift. Patients with thin, inelastic skin also tend to relapse early and form “sweeps” in unnaturally oriented resting skin tension lines along the jawline. These patients benefit from adjunctive skin procedures that thicken and revitalize the dermis, such as resurfacing or radiofrequency tightening.

Muscle/SMAS Laxity

Often muscle/SMAS laxity is most notable in the formation of single or double (multiple) platysmal bands in the submental region. In the facial region, this laxity may manifest as jowling, deep nasolabial folds, and marionette lines. Invariably, there is also some component of skin laxity associated with these findings. The facelift procedure should be designed to allow adequate access to tighten the SMAS/platysmal layer and allow passive redraping of the skin as the facial musculature is repositioned.

Modification of Fat Planes

Fat is distributed in the face and neck in a superficial plane and in a deep plane. The superficial, subcutaneous plane is contiguous throughout the face and neck, with fibrous attachments traversing it, between the deeper SMAS layer and the overlying dermis. The deeper fat planes are found in discrete anatomic pockets and are not as fibrous. In the aging face, the superficial plane often becomes more hypertrophied, whereas the deeper plane atrophies. One goal of the facelift is to sculpturally reduce excess superficial fat. This is typically accomplished with liposuction, direct excision, or suture repositioning. Patients who display fat atrophy, either local to one area or globally throughout the face, may benefit from facial volumizing. This may be accomplished through fat transfer, alloplastic implants, or injectable fillers.

Limitations and Contraindications

Medical Clearance

The facelift is a completely elective procedure. As such, it should be performed only on patients who have an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) 1 or 2 status, since this procedure is typically performed in an outpatient setting.

Anticoagulants

Patients who are unable to halt aspirin or other anticoagulant therapy during the perioperative period should be deferred or offered a limited surgical plan.

Smoking

The effects of tobacco use, particularly nicotine load, on wound healing have been well documented. Some surgeons may refuse to operate on a patient until all smoking has ceased for several months preoperatively. As a matter of practicality, most patients can safely undergo a facelift if they have limited themselves to two or three cigarettes per day.

Beyond these limitations, the main contraindications to the procedure are relative and are often a function of the patient’s perception of the problem and the surgeon’s accurate diagnosis.

Expectations

Most patients have a reasonable expectation of the likely result from facelift surgery. Some studies have suggested that a patient will appear approximately 7 to 10 years younger in the area of the lower face and neck after facelift surgery. Occasionally a patient demands a result that is unobtainable, such as complete elimination of all rhytids in a 75-year-old smoker. An attempt should be made to educate the patient as to the achievable results; however, if a consensus cannot be reached, surgery should be deferred.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder or Mental Illness

Relative Contraindications

Relative contraindications include recognition of adjunctive cosmetic problems and the need for additional procedures to create the patient’s desired correction, as discussed in the following sections.

Skin.

Fine rhytids, dyschromias, and other actinic-related changes of the skin are not a contraindication to the procedure, but the patient should be educated that the facelift will not improve these issues. Often, the patient may remark that dyspigmented patches actually become more apparent after a facelift, as folded and redundant skin is stretched flat. Appropriate skin care, adjunctive resurfacing, and the use of nonablative lasers may be indicated.

Bone.

Patients may have underlying bony deficiencies in the area of the chin, piriform aperture, and/or mandibular angles that may not be favorable to achieving an outstanding cervicomental line angle and overall result. It has been well described that bone loss occurs in these anatomic regions with aging; in other cases, such deficiencies may have been present from a young age. Whenever possible, the surgeon should offer options to augment these areas to a more desirable contour.

Hyoid.

The outstanding facelift result is more likely to be obtained in a patient with a hyoid that is superiorly positioned relative to the mandibular plane and is positioned posterior to the mandibular angle with a long mandibular body. This delineates the inferior aspect of the creation of a sharp cervicomental line angle. When this relationship is not present and a low hyoid is palpated with an A-P short chin, the facelift result is somewhat compromised. Often an obtuse cervicomental line angle is obtained. The facelift may still be performed, but the patient should be shown the results obtained in patients with a similar hyoid configuration to avoid unreasonable expectations and disappointment.

Previous Liposuction/Facelift Surgery/Scarring.

Patients should be made aware that the complication rate often is higher in individuals with a history of previous face/neck surgery. Such complications include scarring, skin compromise, and contour irregularity. These problems also may be seen in patients with a history of severe nodular cystic acne in the areas to be dissected. Patients who preoperatively display fat plane irregularity and dermal tethering are especially at risk for these complications.

Technique: Facelift

Step 1:

Marking

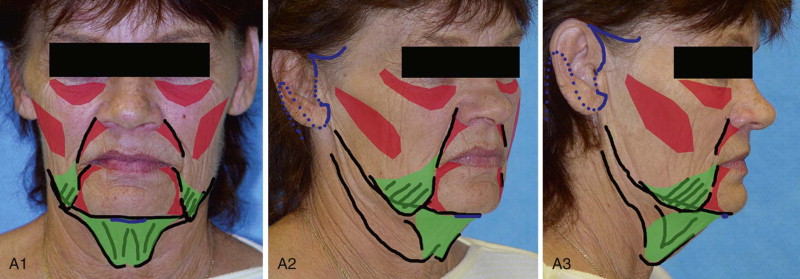

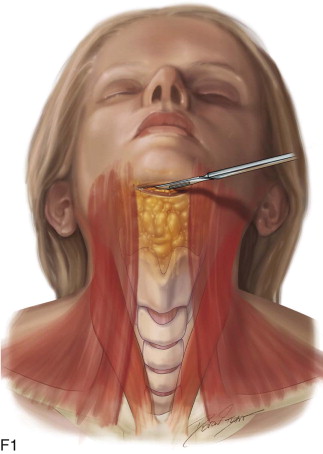

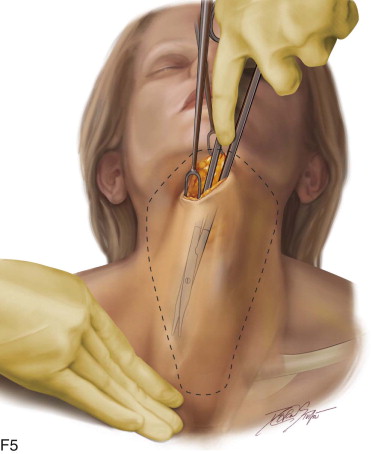

The patient is marked in an upright, sitting position preoperatively. Permanent marker is used to outline the jawline and the level of the hyoid. A topographical style is used to mark fat deposits and deficiencies. The extent of subcutaneous dissection should be marked and the design and placement of the incision determined ( Figure 135-1, A , and Table 135-1 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses