Chapter

14

Ethics and Advertising

Protect and defend your name above all else.

Ethics and Advertising

On its face, advertising serves a useful purpose for consumers. It is beneficial because it provides information about individual businesses offering services that the public may wish to purchase. In any purchasing choice, decisions are made based upon the information that is available. The more information available to patients, for example, the better prepared they will be to make a decision on what is in reality a purchasing decision about their health. So why should they not have information about the training and skill level of the clinician they are considering to treat their vital body parts? Why should they not have as much information as possible about which treatment option they should choose and who will render that treatment? Certainly our legal system has recognized that advertising can play a large role in providing the information that patients may need to make an informed choice of treatment and treater. The problem of course comes when advertising becomes deceptive or unfair such that the consumer is faced with a false choice. This is where the ethics of advertising must be considered.

Ever since the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) started to break down the self-imposed (by state boards of dentistry) restrictions on advertising by dentists, the role of advertising in the profession has been fraught with emotional and political charges and decisions. On the one side you have state boards of dentistry trying to protect the interests of their constituency, which is practicing dentists (state boards are generally made up largely of practicing dentists), and on the other side you have the FTC and the courts trying to make sure that the public is protected from the potential self-interested actions of some state boards, and some dentists who may choose to walk the fine line between ethical and unethical advertising. The promotion of competition is also a goal of advertising and of the FTC, while the profession of dentistry prides itself on collegiality rather than competition. Of course, one hopes that all parties are working with the best interests of the public and the consumer (patients) at heart, but that is not always the case, as we shall see.

In a writing under the title of “Advertising: for good or evil,” Geoffrey Klempner wrote that there are 3 charges that can be leveled against advertisers:1

- They sell us dreams, entice us into confusing dreams with reality.

- They pander to our desires for things that are bad for us.

- They manipulate us into wanting things that we do not really need.

Are these the characteristics that we would wish to be associated with the noble profession of dentistry? I think the answer is very clearly, “No!”

However, at the peak of the recent cosmetic revolution through the 1990s and 2000s, and even today, I think one could argue that some of those charges could have been leveled against a certain segment of our practicing community engaged in exaggeration and hyperbole in attempting to present themselves as experts (if not specialists) in the area of cosmetic dentistry (not a recognized specialty area of course).

At the time, some in this segment of the profession put profits before health. It was a segment that saw self-interest being placed squarely before patients’ interests in many cases, which put short-term profit before long-term benefit.

The fight over advertising was fought and lost by the opponents to advertising in the United States when the FTC ruled that dentists can advertise, provided the advertisement is not false or deceptive. State boards then tried to regulate advertising but found that the bar was placed quite low at “false or deceptive” and thus many dentists got away with advertisements at which most in the profession would cringe. Advertisements can be self-aggrandizing and unprofessional, yet legal. They lure in consumers by preying on their vanity and then manipulating them to want something that they do not need, and that in fact in many cases is harmful to their long-term oral health, and thus to their overall health and well-being.

In the early days of dentistry, advertising had been a historical artifact of harmless self-promotion on business cards and free giveaways from the dental office imprinted with the name of the practice or the dentist. Then we went through a long period from essentially minimal advertising of practices to the point now where most dentists carry out some form of practice information delivery, for example on the World Wide Web, if not all-out advertising ranging from the professionally-endorsed to the tacky, and from the informational to the dishonest and/or self-promotional.

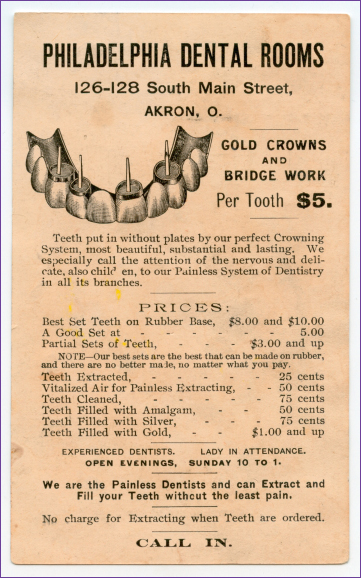

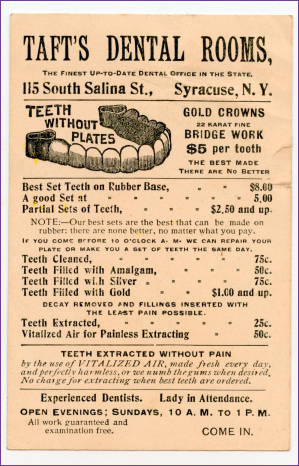

Examples of Victorian era advertising trade cards (courtesy Dr. Theodore P. Croll, Doylestown, PA) can be seen in Figures 14.1 and 14.2. These cards are from circa 1885–1895 and depict some claims that would be called deceptive and unethical today. Claims such as “perfect crowning system” or “painless dentistry” could probably not stand up to scrutiny. Another card talks with apparent hope (false in many cases no doubt) of “painless extracting” while it gets closer to the truth with, “Decay removed and fillings inserted with the least pain possible.” Along with word of mouth, “tradesman’s cards” were the only way to advertise one’s services in seventeenth and eighteenth century England.2

Figure 14.1 A typical Victorian Era dentistry trade card for a well known dental business (circa 1885). Claims of superiority, “painless” extracting, and “perfect Crowning System” are highly suspect.

Although dentists do not use trade cards any more, I have seen advertisements for dentists that are of questionable professional standards in use today, such as on the back of grocery store receipts and on the sides of an advertising van that drives around town (I have seen one in San Diego, CA) with moving screens that promote certain businesses, including dental offices. Today, the most popular form of advertising is surely a well-designed and well-managed Web site. Such a site, with truthful statements about the dentist and his/her team, with perhaps some educational materials available, can be a very positive advertisement for the dentist and the practice. However, it can also be misused as can be seen with a very quick look online where many Web sites for dentists can be seen that exaggerate a dentist’s credentials and are misleading and deceptive in an attempt to get the patient in the door. It seems that here there is a graying of the formerly sharp line between a profession and a trade, at least in terms of advertising standards.

Figure 14.2 This 1880s card claimed TAFT’S DENTAL ROOMS to be the “finest” office in the state of New York, and the crowns and bridges “THE BEST MADE/THERE ARE NO BETTER.” Again, maybe, maybe not, but they are ethically questionable claims for a healthcare practice.

The core of ethical advertising for the dental professional surrounds three issues, the first of which is the issue of trust. Trust is the most fundamental building block of a practice and of the relationship between a dentist and his/her patients. Without trust, an adversarial relationship, such as seen during the purchase of an automobile for example, is set up and there can rarely be a satisfactory outcome of the relationship as each side tries to gain an advantage over the other. There is a complete lack of trust on both sides of this arrangement; both sides being fully aware that the self-interests of both sides are in opposition to each other. The buyer wants the best possible car for the lowest possible price. While the seller, particularly in the case of a used (or “previously owned” as the new term has it) car, is trying to sell the vehicle for more than it is worth. It is trust that leads to the dentist being able to complete the best treatment plan for the patient, who, in turn, is happy to receive such treatment trusting that it has been delivered with his best interests (the patient’s) in mind. But the adversarial relationship is also entering the dental practice as office managers and staff are encouraged to “sell” additional treatments to the patient, or the patient tries to bargain for additional services to be included. This is the inevitable outcome of additional advertising (for example, “free teeth whitening with examination”) and it has been going on since the early trade cards (“No charge for extracting when teeth are ordered,” Figure 14.1). It is unfortunate that it appears the trust factor is decreasing in the dentist–patient relationship today. It can only lead to an erosion of the autonomy of the profession over time.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses