Epithelium

Publisher Summary

This chapter discusses epithelia, which are essentially surface tissues of ectodermal origin. The epidermis covering the surface of the skin on the outside of the body is a typical epithelium. However, epithelia cover the surfaces of other tissues and are not necessarily confined to the outside of the animal; oral epithelium and the epithelial lining of the intestine are examples of epithelia that line the wall of the alimentary canal and are kept moist by the secretion of mucous glands embedded in them. The functions of an epithelium are those that are clearly related to a superficial tissue, namely protection, absorption, and secretion. The relative degree of development of these three functions varies considerably in different epithelia so that it is possible to classify these tissues according to which function predominates. The best known protective epithelia are the epidermis of the skin together with related structures such as nails, hair, and feathers, as well as analogous tissues, including some of specifically dental interest, such as the oral and gingival epithelium. While the masticatory gingival epithelium is covered by a layer of keratin, the neighboring crevicular gingival epithelium and the alveolar mucosal epithelium are not. Epithelia usually form a covering to connective tissue from which they are separated by a basement membrane.

Protective epithelia

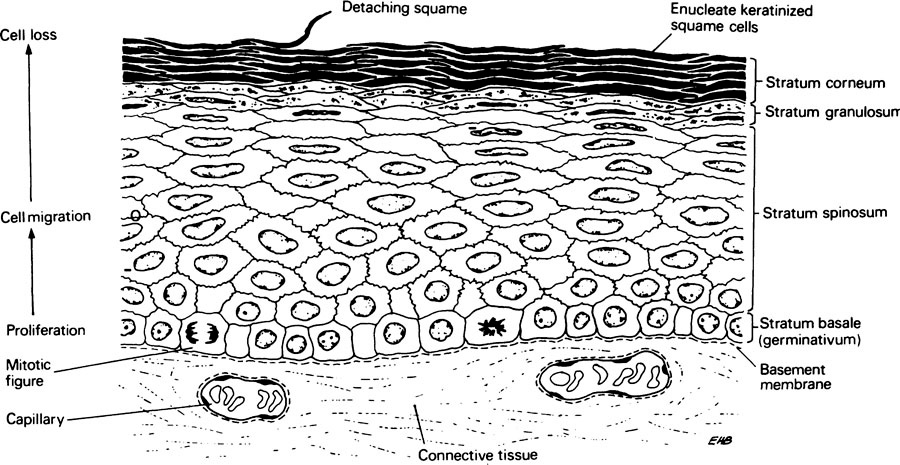

Epithelia usually form a covering to connective tissue from which they are separated by a basement membrane (Figure 26.1). Since epithelium has no blood supply of its own, it derives its nutrients from, and disposes of its waste products into, the neighbouring connective tissue which contains capillaries. There is considerable interaction between epithelial and connective tissue cells which influence each other’s division and differentiation and this interaction presumably takes place across the basement membrane. This structure stains strongly with the periodic acid–Schiff reagent which indicates the presence of glycoprotein which contains unsubstituted sugar residues. The basement membrane is shown by the electron microscope to consist of two distinct parts, a deeper layer consisting of reticulin and a more superficial part, which can in turn be divided into the lamina densa and the lamina lucida. Histologically, reticulin appears as a fine branching network which stains black when treated with solutions containing silver salts, probably as a result of the reducing behaviour of sugar residues in glycoprotein.

The layer of epithelial cells in contact with the basement membrane is known as the stratum basale or germitivum. These basal cells undergo division to replace those that are continually shed from the outer surface of the epithelium (Figure 26.1). Differentiation also begins in the basal layer, most probably as a separate process. As cells differentiate they move away from the basement membrane and become flattened in a direction at right angles to their movement. The rate of cell division in the basal layer balances the rate at which cells are shed from the surface, and it has been suggested that this is controlled by a feedback mechanism involving a water-soluble heat-labile substance or chalone (page 366) produced in the outer layers which suppresses mitosis in the stratum basale.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses