Natural disasters may strike quickly and without warning and cause long-term health consequences beyond the immediate loss of lives and property. Dental professionals have a social responsibility to participate in community emergency preparedness planning and response to mitigate prolonged recovery of the dental care infrastructure in the affected areas. Public health and emergency management agencies should plan for access to emergent dental care as part of a multidisciplinary local emergency response to mitigate the impact of devastation on the primary oral health needs of persons in the affected geographic areas. State dental associations should work with government agencies and emergency management groups to increase awareness of the importance for collaborative emergency response health services in the aftermath of natural disasters.

Background and significance

“Natural hazards are a part of life. But hazards only become disasters when people’s lives and livelihoods are swept away…let us remind ourselves that we can and must reduce the impact of disasters by building sustainable communities that have long-term capacity to live with risk.” —Kofi Annan, Secretary-General of the United Nations, on the occasion of the International Day for Disaster Reduction, October 8, 2003.

The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina spotlighted many far-reaching consequences beyond the local loss of lives and properties, including the displacement of more than 750,000 victims, an increase in global fuel prices after the closure of oilrigs in the Gulf of Mexico, and even a record trade deficit for the United Kingdom . Hurricane Katrina affected the lives and the livelihoods of many health professionals, and the destruction of public health and medical care infrastructure in the affected areas was unprecedented. All 14 hospitals and three federal medical facilities in the lower six counties of Mississippi were damaged, and 11 hospitals in the New Orleans area were flood-bound. Sanders reported that Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center’s School of Medicine experienced a significant loss in patients, departmental faculty and staff, practice and office space, and graduate medical education funding and subsequently lost millions of dollars in clinic revenue. The impact on health care systems was also far-reaching. The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center reported having operational losses of $16 million caused by a loss of hotel beds for their consultation patients, loss of referring physicians, and a 4-day operations shutdown in response to Hurricane Rita in September 2005 .

Sariego observed that disasters create chaos and disrupt the normal functioning of the affected community, including its health care infrastructure and resources. Many publications in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina described how a lack of hospitals and physicians impacted the delivery of medical services, but they largely ignored how the disaster affected the delivery of nonallopathic services, such as dental care. The American Dental Association reported that Hurricane Katrina affected the lives of an estimated 1185 licensed dentists, 49% of whom lived in Louisiana and 21% in Mississippi . In September 2005, an initial assessment of the affected areas in Mississippi revealed that more than 85 dental offices were partially or completely destroyed and 44 dentists lost their homes.

Estimating that the average dentist provides care to 52.2 patients per week, more than 303,000 monthly patient visits were disrupted in the immediate recovery after the storm, which resulted in an estimated revenue loss of $63 million per month . Subsequently, many dentists experienced prolonged displacement and family disruptions, some experienced the complete loss of their business, and some experienced the loss of patients and auxiliary staff, which motivated some dental workers to consider relocation from the affected areas to avoid financial hardships. Individuals who experienced Hurricane Katrina have a better understanding of disaster preparedness through the hardships endured and the lessons learned. The dental profession, by virtue of its commitment to comprehensive primary health care, should be as engaged as allopathic providers in disaster mitigation planning. By participating in emergency management planning, the dental profession can mitigate prolonged recovery of the dental care infrastructure and improve the odds of having sustainable systems of dental care in the aftermath of devastation.

Mitigation is the process of anticipating risks to life and property and implementing actions that reduce or eliminate these risks. It is the first phase of emergency management planning that also includes preparedness, response, and recovery in the national response plan . Mitigation is used to implement long-term measures to prevent hazards from developing into disasters altogether or reduce the effects of disasters ( Fig. 1 ).

Effective mitigation planning identifies and evaluates hazards and makes predictions by measuring risks and vulnerability from such hazards. Mitigation may reduce or eliminate risk from hazards: the higher the risk, the more urgent the need to minimize hazards through mitigation. Structural mitigation uses technology-based measures (eg, construction of flood levees or installation of automatic shut-off valves for gas lines) to reduce or eliminate damage. Nonstructural mitigation uses legislation, regulations, and insurance (eg, authorization of land-use zoning to turn flood-prone areas into nonresidential natural habitats) or insurers managing and underwriting hazard insurance.

The dental profession should use mitigation planning to anticipate the risk for hazards and determine where it is safe to build or purchase a clinic facility. Areas that have a higher risk of flooding can be identified by review of topographic flood plain maps to identify flood-prone areas. Dentists can plan by identifying the zoning and building code requirements at the proposed clinic site. The purchase of property that is exposed to flooding or coastal erosion of storm surge should be avoided; the dentist should consider relocating the property to higher ground or ensure that the facility is constructed on posts high above the flood plain. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) provides access to flood plain maps that can be viewed online at the FEMA mitigation Web site ( Fig. 2 ) at http://msc.fema.gov/webapp/wcs/stores/servlet/FemaWelcomeView?storeId=10001&catalogId=10001&langId=-1 .

Dental providers may not have the knowledge or time required to effectively anticipate hazards and risks. Professional hazard mitigation specialists can be used to perform risk assessment surveys and make recommendations on the purchase of property or hazard-related insurance. Mitigation planning differs by geographic location and the probability of risks that occurs in that location. For example, mitigation planning in communities with greater risk for earthquake or high-strength winds may incorporate seismic design standards and wind-bracing requirements in building design and construction to mitigate risk. In the aftermath of a disaster, the federal government can provide mitigation support through Section 404 of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act. After a declaration of disaster has been made, FEMA is authorized to provide grants to states and local governments to implement long-term hazard mitigation measures. These grants may be used to elevate flood-prone structures, retrofit structures to minimize damage in future disasters, and make building code improvements during postdisaster reconstruction. FEMA provides information about the National Flood Insurance Program on the Web at http://www.fema.gov/about/programs/nfip/index.shtm and offers an online mitigation best practices portfolio at http://www.fema.gov/plan/prevent/bestpractices/index.shtm .

Comprehensive mitigation planning also should anticipate and prepare for the risks posed by environmental health effects and communicable disease outbreaks. An immediate consequence of natural disasters is the loss of water for drinking and handwashing, spoilage of food from the lack of refrigeration, and loss of functional sanitation facilities . Environmental exposure to mercury, radiation, and organic compounds used in disinfection may occur as a result of the devastation of a dental clinic facility. The dental profession should advocate for additional state and federal resources to mitigate the environmental impact of these potential exposures. FEMA provides information about environmental contamination risks and has links to resources for natural disasters action plans on its Web site at http://www.epa.gov/greenkit/q5_disas.htm .

A personal mitigation plan for dentists, their families, and staff is recommended to anticipate the loss of basic resources such as water, electricity, gas, and telephones. Emergency preparedness kits can be assembled that contain essential supplies, including flashlights, fresh batteries, battery-powered radio, basic medical aid supplies, and nonperishable foods and drinking water to last several days. Reminder checklists of the important steps to take before, during, and after a disaster should be kept in a handy location because a disaster can strike quickly and without warning. A listing of local evacuation procedures should be included with the checklists. The location of emergency shelters and back-up suppliers for vital resources, such as gasoline and water, should be identified. Employees and family members should share contact information, including cell phone numbers, email addresses, and a location where they plan to stay during and after an emergency crisis event. Planning to ensure reliable modes of communication is essential. Hurricane Katrina’s devastation revealed how all traditional modes of communication failed, including cell phone service. Text messaging proved to be the most reliable means of public communication in the affected areas.

Another consequence of devastation is the loss of staff and dental patients. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, most providers did not anticipate the long-term dispersal of so many people across the nation. Many patients who remained locally in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina were unable to contact their dental providers. Abdel-Monem and Bulling noted an absence of understanding about the potential liability that mental health care providers face in the aftermath of disaster recovery. The potential liabilities that dental providers would face in Katrina’s aftermath were unanticipated. For example, could dental patients claim abandonment because they were unable to contact their dental provider in a reasonable period of time after the disaster occurred? Dentists should prepare for the likely event that a dental practice will close for extended periods and inform patients about what to do if emergent care is needed and how treatment in progress will be completed (eg, the delivery of a denture).

Dentists can use mitigation planning to resume their clinical practice as quickly as possible by identifying an alternate location to temporarily relocate their dental practice in the event of building damage and having a plan to re-establish communication with patients. Important documents for clinical operations, such as verification of licensure, malpractice insurance, and patient records, should be stored in portable travel containers or copied and stored in a secure location for future retrieval. Providers can protect access to their patient records by using Web-accessible electronic patient records that allow the retrieval of databases from distant sites. Electronic dental records are widely available that include storage for digital photographs, which may assist with postmortem identification in mortuary operations. Databases should include patient contact information, including addresses of individuals’ preferred evacuation sites, and all staff credentialing documentation, which ideally should be converted to digital format. If a cell phone number is recorded, it may be helpful to identify if the cell phone service allows text messaging. All patients should be informed of local hazard risks and receive guidance to prepare for disasters.

It is not an overstatement to say that the dental profession has a social responsibility to mitigate prolonged recovery of the dental care infrastructure and participate as health care providers in disaster response emergency services. Dentists should consider participation in local emergency response units. Local response units provide first response assistance to victims of disasters and coordinate early medical response. It is important to establish a sense of teamwork, strengthen communications for first responders, and understand the legal ramifications. Volunteer participants must receive emergency management training and education to participate. Many dentists have the capacity to perform various emergency response activities, including postmortem identification, assistance in fatality management, triage and prehospital care, and emergency dental treatment in mass care operations. Such social responsibility would provide community-level involvement and enhance long-term recovery. Dental education programs should prepare instruction and hands-on experiences for students and residents in all phases of emergency preparedness planning, including how traumatic events may affect them and their families emotionally to better prepare psychologically . Students should receive instruction in the use of hazard mitigation maps to plan the location of a dental practice.

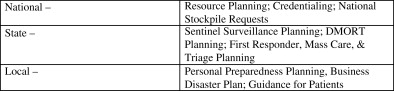

Most states have public health dental directors who provide leadership for state oral health programs in public health agencies. State oral health programs should participate in public health emergency planning and response at the state and local levels and be familiar with federal planning activities ( Fig. 3 ). Readiness means the ability to respond immediately, and public health dental directors must know how best to act and cope during terrorism events and other public health emergencies. Dental directors should be familiar with emergency support function’s #6, #8, and #14, the federal government’s emergency response framework for mass care, public health and medical services, and community recovery and mitigation planning. Mississippi’s experience in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina demonstrated that the American public expects and demands efficient emergency public health and medical services. To improve these services, dentists must be included in multidisciplinary care response teams, and patient triage and transfer operations should include access to emergency dental services .