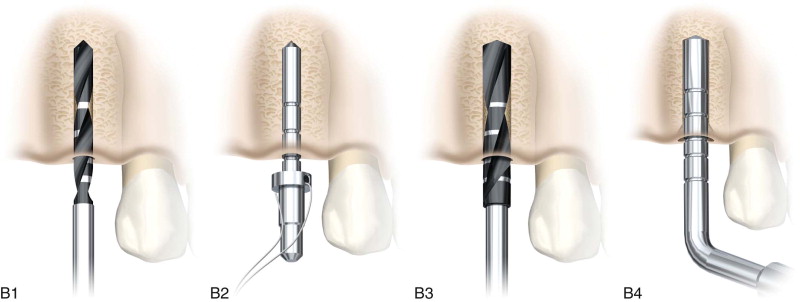

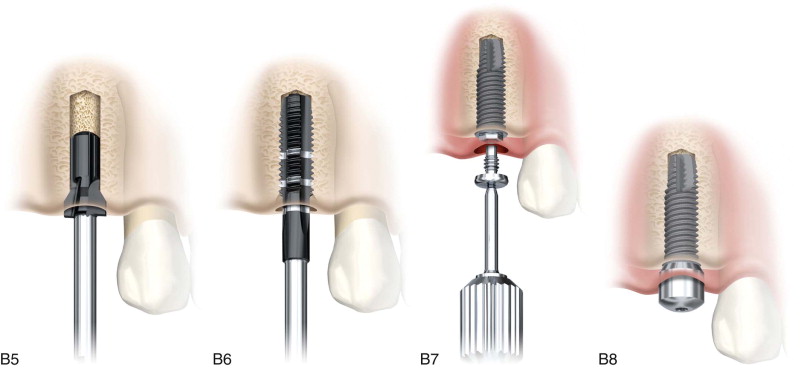

Armamentarium ( Figure 19-1 )

|

History of the Procedure

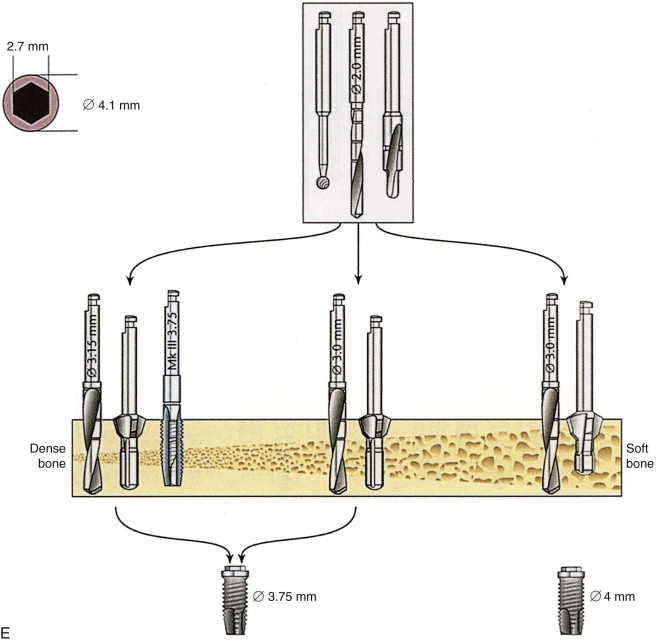

Dental implants are thought to date back to Mayan times, when seashells were trimmed and shaped before being hammered into the jaw to replace missing teeth. Numerous dental practitioners participated in advancing the art of dental implantology to solve the scourge of edentulism. These clinicians were working with various materials, such as steel, chrome cobalt, and vitreous carbon, with varying results. Clinicians such as Linkow and Dorfman, Roberts, Duke, Gershoff, Goldberg, Small and Tatum were visionaries, innovators dedicated to treating edentulism. However, it was Dr. Per-Ingvar Brånemark who revolutionized the art and science of dental implantology with his discovery of the utility of titanium in 1952 while studying methods to improve orthopedic surgery. He discovered that bone would bond irreversibly to implanted titanium screw-shaped cylinders. He demonstrated, under carefully controlled conditions, that at the light microscopic level, titanium could structurally integrate with living bone. He further defined the surgical procedure for implantation, emphasizing careful technique, minimizing injury to bone by controlling overheating through the use of a series of increasingly larger drills with copious irrigation, and then allowing a healing period for integration of bone with titanium bone cylinders. He further confirmed that this could be achieved with a high degree of predictability and without long-term soft tissue inflammation, fibrous encapsulation, or implant failure. Implant surface technology was advanced by Schroeder and Letterman, who developed a titanium plasma spray coating with a one-piece transmucosal screw.

These scientific advances, in addition to recognition of the need for better ways to replace missing dentition, have revolutionized dentistry in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

History of the Procedure

Dental implants are thought to date back to Mayan times, when seashells were trimmed and shaped before being hammered into the jaw to replace missing teeth. Numerous dental practitioners participated in advancing the art of dental implantology to solve the scourge of edentulism. These clinicians were working with various materials, such as steel, chrome cobalt, and vitreous carbon, with varying results. Clinicians such as Linkow and Dorfman, Roberts, Duke, Gershoff, Goldberg, Small and Tatum were visionaries, innovators dedicated to treating edentulism. However, it was Dr. Per-Ingvar Brånemark who revolutionized the art and science of dental implantology with his discovery of the utility of titanium in 1952 while studying methods to improve orthopedic surgery. He discovered that bone would bond irreversibly to implanted titanium screw-shaped cylinders. He demonstrated, under carefully controlled conditions, that at the light microscopic level, titanium could structurally integrate with living bone. He further defined the surgical procedure for implantation, emphasizing careful technique, minimizing injury to bone by controlling overheating through the use of a series of increasingly larger drills with copious irrigation, and then allowing a healing period for integration of bone with titanium bone cylinders. He further confirmed that this could be achieved with a high degree of predictability and without long-term soft tissue inflammation, fibrous encapsulation, or implant failure. Implant surface technology was advanced by Schroeder and Letterman, who developed a titanium plasma spray coating with a one-piece transmucosal screw.

These scientific advances, in addition to recognition of the need for better ways to replace missing dentition, have revolutionized dentistry in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

The placement of dental implants is indicated to support tooth replacements in edentulous and partially edentulous arches. Endosteal root form implants have been shown to support crown and bridge replacement for missing teeth in a very predictable manner, with low failure and complication rates. Implant and prosthetic design and service characteristics have improved success rates and shortened the osseointegration period before loading. Quantitative measures of torque and resonance frequency analysis (implant stability quotient [ISQ]) can be used to guide the timing for loading of an implant; torque values of 35 Ncm or higher and/or an ISQ of 70 or higher indicates implant stability sufficient to support immediate loading of the implant ( Figure 19-2 ).

Patients who are missing teeth may be good candidates for an implant-supported prosthesis. Patients who are edentulous in the mandible, in particular, may not be able to comfortably manage a normal-textured diet because of the mobility of the denture. After tooth removal the alveolar bone resorbs, and the bone loss in height and width causes a poor fit for the removable denture; in addition, dislodgement from the perioral musculature becomes greater than the retentive forces of the denture, which moves on the edentulous ridge, causing discomfort and dysfunction. Dental implants provide excellent support for a prosthesis in an edentulous arch and improve the patient’s ability to function and socialize. Likewise, the use of implants to support a prosthesis in partially edentulous patients may eliminate the need for crown prep on teeth adjacent to the edentulous space that will be used as bridge abutments. This preserves dental structure and encourages healthier mouths. If removal of nonfunctioning or nonrestorable teeth is necessary, it is advisable to consider the best replacement choice for that particular patient; if an implant-supported prosthesis is indicated, extraction and immediate implant placement should be considered based on the diagnosis and treatment planning. This may minimize resorptive alveolar bone loss after extraction and allow for a less complex restoration.

Dental implants are indicated to support natural tooth replacements in both edentulous and partially edentulous sites and in minimally and severely resorbed alveolar bone because it has been shown that osseointegrated implant-supported restorations can arrest or minimize the natural progression of alveolar bone loss after tooth removal. Implant placement and function can minimize the morbidity of edentulism and improve function and quality of life for these patients.

Limitations and Contraindications

-

Inadequate or excessive vertical restorative space

-

Limited jaw opening and restricted interarch distance

-

Inadequate alveolar width for optimal buccolingual positioning

Medically Compromised Conditions

-

Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus

-

Long-term therapy with an immunosuppressant medication

-

Connective tissue disease (e.g., uncontrolled systemic lupus erythematosus or scleroderma), autoimmune diseases

-

Blood dyscrasias and coagulopathies

-

Intraoral and perioral malignancies

-

Irradiation of the jaws that may lead to radiation necrosis

-

Intravenous bisphosphonate treatment for malignancy or osteoporosis

-

Severe psychological disorders

-

Alcohol and drug addiction

-

Prolonged use of corticosteroids

Relative Local Contraindications

-

Insufficient quantity or quality of bone

-

Uncontrolled periodontal disease

-

Severe bruxism

-

Unbalanced relationship between the maxilla and mandible (severe Class II or Class III malocclusion)

-

Poor oral hygiene

Technique: Implant Placement in Edentulous (Healed) Alveolar Sites

Diagnosis and treatment planning are critical to the execution of implant placement and should be performed as part of a team effort. The process should include an examination, clinical and radiographic analysis, and laboratory aids and support as indicated.

Step 1:

Initial Evaluation

The examination should encompass the entire oral cavity, including the dentition and edentulous sites, jaw relationship, and occlusion. The edentulous areas should be evaluated for height, width, and length of the proposed operative site. The character of the gingival soft tissue and the amount and location of attached and unattached tissue should be assessed and recorded. Remaining teeth should be free of decay and periodontally healthy.

Step 2:

Imaging

Inherent diagnostic limitations (e.g., distortion in conventional radiology) have been significantly improved by new technologies such as computed tomography (CT). CT allows reformatting of a volumetric dataset in axial, coronal, and sagittal cuts and the building of multiple cross-sectional and panoramic views. Such preoperative radiographic images can be uploaded into three-dimensional (3D) implant planning software to expand the indications for oral implant–based treatments. CT also enables protection of critical anatomic structures and provides the esthetic and functional advantages of prosthodontics-driven implant positioning.

Step 3:

Surgical Guide

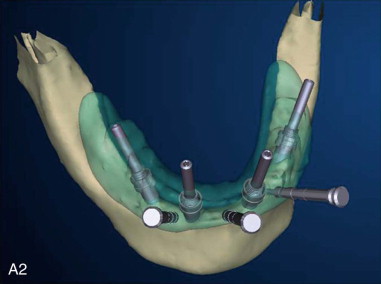

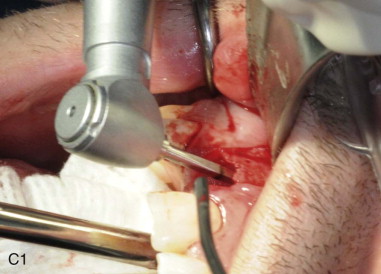

Once implant treatment planning has been determined, the data can be sent to manufacturing facilities for a guide splint and prosthesis construction. Some advantages of this technology are reduced operating time, minimal surgical trauma, a shorter postoperative recovery period, and less pain ( Figure 19-3, A ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses