Introduction

Enamel demineralization and gingival inflammation are the most prevalent consequences of biofilm formation in orthodontics. Our hypothesis was that educating patients about the severe consequences of biofilm accumulation could enhance their oral hygiene while wearing fixed appliances.

Methods

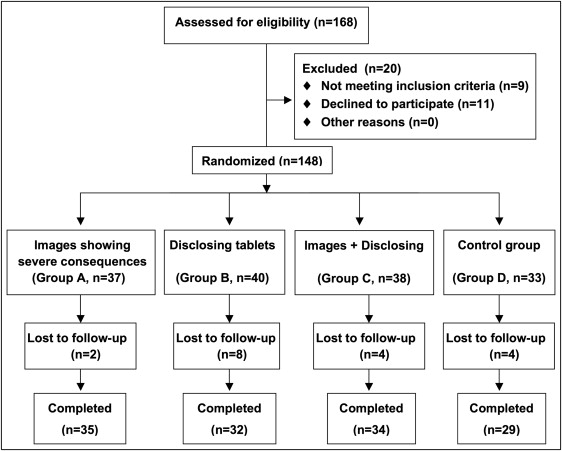

This study was designed as a randomized controlled 4-arm parallel trial. A total of 148 participants in Chengdu, China, matching the eligibility criteria of 11 to 25 years of age, at least 20 natural teeth, and a treatment plan that included conventional stainless steel brackets, were randomly assigned to 4 intervention groups based on computer-generated random sequencing using simple randomization without blocking. In group A (n = 37), the subjects were shown images illustrating the severe consequences of biofilm formation, including enamel demineralization and gingival inflammation; subjects in group B (n = 40) were given biofilm disclosing tablets; those in group C (n = 38) received a combination of A and B; the subjects in group D (n = 33) served as the controls. The investigators were blinded to the allocations, and the researcher managing the random sequence did not participate in allocation or measurement. All groups received routine oral hygiene instructions. Plaque index and gingival index scores were recorded at each appointment during a 6-month follow-up.

Results

Eighteen participants were lost during follow-up, resulting in a total of 130 participants after the trial (group A, 35; group B, 32; group C, 34; group D, 29). No adverse events were recorded. Groups A and C exhibited a significantly lower plaque index scores (parameter-estimate [95% confidence interval] = −1.20 [−1.76 to −0.63] for group A, and −1.12 [−1.69 to −0.56] for group C) and gingival index scores (−0.13 [−0.21 to −0.04], and −0.19 [−0.28 to −0.10]), respectively, compared with group D ( P <0.001 for all), whereas no significant difference was found between groups B and D, or between groups A and C ( P >0.05). The adults had significantly lower plaque index (0.48 [0.13-0.84], P <0.001) and gingival index (0.06 [0.01-0.11], P = 0.018) scores than did the teenagers, and the female subjects had significantly higher gingival index (−0.06 [−0.11 to −0.01], P = 0.040) scores than did the male subjects.

Conclusions

The use of images showing the severe consequences of biofilm accumulation enhanced the oral hygiene of patients treated with fixed appliances.

Enamel demineralization and gingival inflammation are the most prevalent consequences of biofilm formation in orthodontics, affecting 50% to 70% of patients with fixed appliances. The presence of fixed orthodontic appliances severely impedes toothbrushing and creates stagnant areas for biofilm adhesion. If patients do not maintain good oral hygiene, the biofilm can cause serious consequences such as enamel demineralization, gingival inflammation, and caries. These complications can have a significant impact on patients’ oral health and quality of life. Thus, it is essential to maintain good oral hygiene during orthodontic treatment.

Clinicians routinely provide oral hygiene instructions to orthodontic patients, sometimes supplemented with written information or disclosing agents to show the location of the biofilm; however, compliance rates are as low as 50%. Extensive research has been carried out to enhance the effectiveness of oral hygiene instructions. An application of phase-contrast microscopy and biofilm disclosing agents has been reported to improve oral hygiene instructions; however, this approach is too complicated for routine clinical practice. Oral health counseling has been reported to increase biofilm removal efficacy and improve control of gingival inflammation. Demonstrating the brushing technique with a model, supplemented by verbal instructions, illustrations, or videos, appears to be an effective method for patients to adopt and maintain a brushing technique, but the follow-up of the study was only 4 weeks, and the long-term effectiveness of this approach is still unknown. Computer-based methods such as videos showing patients the steps to maintain oral hygiene were found to be better than verbal and written information, but their efficacy and long-term effectiveness are unsatisfactory.

Patient compliance was found to be influenced by psychological and sociodemographic traits. Improvement in patients’ understanding of the severe consequences of poor oral hygiene might warn them and promote good oral hygiene.

In this clinical trial, we tested the efficacy of visually aided oral hygiene instructions for enhancing oral hygiene in patients wearing fixed orthodontic appliances. The visual aids consisted of images illustrating the possible severe consequences of biofilm accumulation.

Material and methods

The study was designed as a prospective, randomized controlled 4-arm parallel trial. We recruited 148 patients (age range, 11-25 years) wearing fixed orthodontic appliances in Chengdu, China ( Fig 1 ). The determination of sample size was based on previous estimates of plaque index (PI) variability (SD, 0.4) in adolescents requiring orthodontic treatment by setting type I error at 0.05 and type II error at 0.20 (80% power). We assumed that participants were treated with plaque-disclosing tablets and found that about 27 patients (ie, a total of 108 for 4 groups) were needed to detect a decrease in the PI of about 30% (the PI was expected to decrease from 1.1 before treatment to 0.8 after treatment). To account for possible dropouts during the study, we therefore aimed to recruit 148 patients ( Fig 1 , Table I ). The trial was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR-PCS-12002443).

| Group A (n = 35) | Group B (n = 32) | Group C (n = 34) | Group D (control) (n = 29) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ∗ | ||||

| ≥18 y | 21 (60%) | 19 (59%) | 20 (59%) | 16 (55%) |

| <18 y | 14 (40%) | 13 (41%) | 14 (41%) | 13 (45%) |

| Sex ∗ | ||||

| Female | 20 (57%) | 20 (62%) | 19 (56%) | 18 (62%) |

| Male | 15 (43%) | 12 (38%) | 15 (44%) | 11 (38%) |

| PI † | 2.3 (1.1) | 2.3 (0.8) | 2.4 (1.2) | 2.3 (0.8) |

| GI † | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.2) |

∗ Data represent number (percentage) of participants in each group

All participants were informed of the study design, and written, informed consent was obtained from the patients and the parents before the study. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of West China School of Stomatology, Sichuan University (WCHSIRB-ST-2012-028), Chengdu, China.

Eligible participants had to match the following inclusion criteria: age 11 to 25 years, at least 20 natural teeth (extraction and nonextraction patients), willing to wear conventional stainless steel brackets (Victory Series; 3M Unitek, Monrovia, Calif) in both arches, and willing to participate in the study and to sign an informed consent form.

The following conditions were considered to be the exclusion criteria: systemic disease such as diabetes, periodontal disease, extensive dental restorations, dental fluorosis, antibiotic therapy or dental treatment affecting oral hygiene or gingival health during the study, smoking, and use of powered tooth brushes.

A simple randomization with no blocking was used in the study. Eligible, consenting patients were randomly assigned to 4 groups based on computer-generated random sequencing. A test of baseline balance across treatment groups was performed after randomization. To avoid selection bias, we concealed the allocation. The investigator (Y.P.) was blinded to the allocation, and the researcher (R.W.) managing the random sequence did not participate in allocation or measurement. Another certified researcher (W.W.) explained the study and introduced oral hygiene to the participants and their parents according to the random sequencing, which was provided in opaque, sealed envelopes at the initial appointment before bonding.

In consideration of the ethical issues and patients’ equal rights for oral health, all groups received routine oral hygiene instructions. The patients were then randomly assigned to 1 of the following 4 intervention groups.

-

Group A: Images illustrating the severe consequences of biofilm accumulation, including enamel demineralization and gingival inflammation, were shown ( Fig 2 ).

Fig 2 Images illustrating the severe consequences of biofilm accumulation, including enamel demineralization and gingival inflammation. -

Group B: Biofilm-disclosing tablets (GUM Red-Cote; Butler, Chicago, Ill), showing the location of the biofilm, were distributed.

-

Group C: A combination of A and B.

-

Group D: Control group (routine oral hygiene instructions only).

The routine oral hygiene instructions used in this study involved chairside verbal instructions in toothbrushing (modified Bass technique), basic information on biofilm, and daily dietary suggestions during orthodontic treatment. All interventions were performed at each appointment by the investigator (Y.P.), who was blinded to the allocation.

To reduce the possible influence of such factors as toothbrushes, toothpastes, brushing techniques, and ligating methods on the study outcomes, all participants received complimentary tubes of toothpaste (Crest; Procter & Gamble, Cincinnati, Ohio) and toothbrushes (Oral B Classic Care Toothbrush; Procter & Gamble) every 2 months during the study, and they were asked to brush at least 3 times daily for 3 minutes each time. They were required to perform the modified Bass brushing technique immediately after their biofilm check, and mistakes during brushing were rectified to ensure that all patients mastered the same correct brushing technique. Orthodontic archwires were ligated using stainless steel ligatures instead of elastomeric rings at each appointment.

All measurements were taken by a calibrated examiner (Y.P.), who was blinded to the patient’s group allocation. This examiner had been trained by a periodontal specialist for measuring the PI and the gingival index (GI). The consistency of the examiner’s measurements was tested using the kappa consistency test in the pilot trials. The PI and the GI scores for all teeth except the second and third molars were measured and recorded. The PI and the GI scores of each patient were calculated by dividing the sum of the scores by the number of teeth measured.

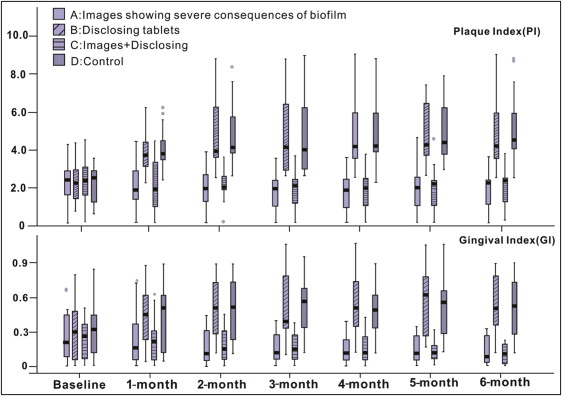

All subjects were followed for 6 months. In addition to baseline ( Table I ), PI and GI values were recorded at each monthly appointment before the orthodontic treatment session, from baseline to the 6-month intervention ( Fig 3 ).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 17.0 for Windows; SPSS, Chicago, Ill) and MLwiN 2.25. The Kruskal-Wallis H rank sum test and the chi-square test were used for baseline comparisons. Polynomial models of the PI and GI scores were generated using MLwiN 2.25, and multilevel modeling software was used for the repeated measurement data. The results of parameter estimates were considered statistically significant at P <0.05. Two separate sets of polynomial models were fitted for the PI and GI scores. The treatment time (T0, T1, …T6) was the first level unit, and the participant was the second level unit. The following covariates were included in the model: sex, age, and treat-time (the interaction between treatment and time). Data analysis was blinded.

Results

The study was conducted between February and December 2012 at West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University. The baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table I . Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the clinical trial. One hundred sixty-eight patients were enrolled and assessed for eligibility. Nine patients did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 11 declined to participate, resulting in a total of 148 recruited for randomization (group A, 37; group B, 40; group C, 38; group D, 33) ( Fig 1 , Table I ). After the 6-month follow-up, 18 participants were lost because of lack of time or unwillingness to continue with the study, resulting in an overall of loss to follow-up of 12% (group A, 35; group B, 32; group C, 34; group D, 29). An intention-to-treat analysis was not performed, and only data of participants who completed the trial were included for analysis. No adverse events were recorded during the trial.

Groups A and C had significantly lower PI scores (parameter-estimate [95% confidence interval] = −1.20 [−1.76 to −0.63] for group A, and −1.12 [−1.69 to −0.56] for group C), and GI scores (−0.13 [−0.21 to −0.04], and −0.19 [−0.28 to −0.10]), respectively, compared with group D after the 2-month interventions ( P <0.001 for all), whereas no significant difference was found between groups B and D, or between groups A and C throughout the follow-up period ( P >0.05) ( Table II , Fig 3 ). The estimates of effect of the 4 groups are summarized in Table III .

| Index | Variable | Parameter estimate | 95% CI (lower) | 95% CI (upper) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | Treat A ∗ | −1.20 (0.29) | −1.76 | −0.63 | <0.001 |

| Treat B † | −0.06 (0.29) | −0.63 | 0.52 | 0.852 | |

| Treat C ∗ | −1.12 (0.29) | −1.69 | −0.56 | <0.001 | |

| Treat A-time ‡ | −0.42 (0.05) | −0.51 | −0.34 | <0.001 | |

| Treat B-time † | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.709 | |

| Treat C-time ‡ | −0.43 (0.05) | −0.52 | −0.34 | <0.001 | |

| Time § | 0.37 (0.03) | 0.31 | 0.44 | <0.001 | |

| Sex † | 0.07 (0.20) | −0.31 | 0.46 | 0.713 | |

| Age ‖ | 0.48 (0.18) | 0.13 | 0.84 | <0.001 | |

| Intercept ¶ | 3.10 (0.24) | 2.63 | 3.56 | <0.001 | |

| GI | Treat A ∗ | −0.13 (0.04) | −0.21 | −0.04 | <0.001 |

| Treat B † | 0.01 (0.04) | −0.07 | 0.10 | 0.769 | |

| Treat C ∗ | −0.19 (0.04) | −0.28 | −0.10 | <0.001 | |

| Treat A-time ‡ | −0.04 (0.01) | −0.05 | −0.02 | <0.001 | |

| Treat B-time † | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.366 | |

| Treat C-time ‡ | −0.03 (0.01) | −0.04 | −0.01 | <0.001 | |

| Time † | 0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.486 | |

| Sex § | −0.06 (0.03) | −0.11 | −0.01 | 0.040 | |

| Age ‖ | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.018 | |

| Intercept ¶ | 0.35 (0.04) | 0.28 | 0.42 | <0.001 |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses