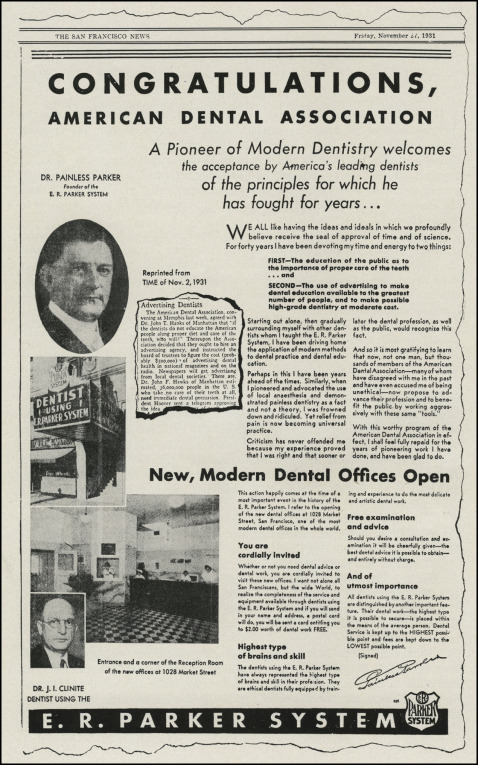

In my trek through history over this past year, some pages of the AJO-DO produced surprises that were intriguing to ponder. One of these was an advertisement that appeared in 1932 involving the “E. R. Parker System” ( Fig 1 ). Here is little bit of his story.

Edgar Rudolph Randolph Parker was born in Canada in 1872. As a young lad, he sought to earn a little money as a peddler by traveling the back roads in a horse-drawn wagon selling items that people might need or want. Later, he enrolled in a seminary and a college but was unsuccessful in both endeavors. He then became a sailor; this was a natural choice, since his father and numerous relatives had been sailors and shipbuilders. Alas, his sailing days were not pleasant: he wound up in jail in South America, was hurt in an accident, caught dengue fever, and was seriously injured in an assault. He returned home to contemplate what to do next with his life and, after consulting with his parents, chose a career in dentistry.

He was admitted into a dental program at the New York College of Dentistry, but he was promptly expelled because the faculty learned that he was making money on the side by going door to door pulling teeth. Parker was later accepted into the Philadelphia Dental College (now Temple University) and graduated in 1892.

Diploma in hand, this very young dentist set up his office in his hometown of St Martins in New Brunswick, Canada. To attract a clientele, he did all the “right things.” He joined and became active in a church and various civic organizations, hoping that he would become better known and patients would come to his practice. Unfortunately, during the first 4 months of practice, he only had one patient (a tourist), who netted him 75 cents.

During those times, dental offices were small one-person operations, and practicing dentistry was difficult. The public had little interest in caring for their teeth, and going to the dentist was unusual except for the extraction of an aching tooth. Dental products were not widely available or used; toothbrushes of the time were made of animal bristles and hair (hogs, horses, badgers). The expectation of the public was that everyone would lose all their teeth by age 40 or before.

Parker believed that ignorance, lack of money, and pain were the main deterrents to proper dental care, with pain as the strongest. He was also disheartened by the attitude of organized dentistry and the prevailing ethical standards that prohibited solicitation of patients. So, Parker rebelled and decided that if the patients would not come to him, he would go to them. In doing so, he launched a system that would bring him fame, fortune, and fierce condemnation from all of dentistry.

He rented a brightly painted horse-drawn wagon onto which he placed a dental chair and set off with his cornet across the area to give a one-man concert and a lengthy lecture on tooth decay, oral hygiene, and the value of dentistry. This was followed by a series of extractions involving people from the audience who were led to believe that the process would be painless.

He accomplished this by persuasion and distraction, and through the abundant use of whiskey and a homemade anesthetic brew whose basis was cocaine (“hydrocaine”); he applied this directly into the cavity. An extraction cost 50 cents; those brave enough to have a tooth extracted were promised $5 in return if they experienced pain. He was a natural salesman.

After becoming successful in this endeavor, he took his show on the road to cities and rural areas across Canada, Alaska, and northern portions of the United States. He eventually set up shop in Brooklyn (1897) and announced “Painless Parker was in business.” He established a grand office in 1900 with outside signage that was large, gaudy, and grandiose in its claims; to be fair, such advertising was not unusual in the dental parlors of New York at the time, many of which also promised extractions that were painless, but were not (novocaine was not invented until 1906). He was also a street dentist and preached like an evangelist about the benefits of dentistry to all who would listen.

Even though established in New York, he did not give up his road show. In fact, the “Parker Dental Circus” became grander with a 15-piece band, buglers, tattooed ladies, contortionists, “the human skeleton,” and dazzling dancing girls. After a lecture, the extractions would begin. The first “patient” extraction was usually a sham in that the patient was a member of the Parker troupe, a tooth was palmed, and the extraction was “performed” and announced with the tooth held high in the forceps, with the patient testifying there was no pain at all…and the crowd cheered. Subsequently, for other patients, the band was very important to his success, for at the moment of extraction a signal was given and the band played loudly, drowning out the patient’s moans. At one stop, he extracted 357 teeth; he claimed this was a personal record for one day. Of course, there were also handbills, posters, and advertisements in the newspapers. He continued this activity well into the 1930s.

Upon the death of a business partner and wanting to expand, Parker moved to Los Angeles in 1912 and later to San Francisco. As he moved around, he set up more offices, all of which had glorious signage. He also developed and sold Painless Parker dental products (mouthwash, toothpaste, and so on). He used airplanes to tow advertising banners. He made educational films about oral hygiene. He had a nationally syndicated call-in radio show about dentistry. He saw to the dental needs of zoo animals (he called this “hippodontia”). He also became a celebrity dentist, treating many glamorous movie stars of the time. In fact, movies were made loosely based on his life (Bob Hope played “Painless” Potter, a hapless dentist, in a Western called “The Paleface”). Wherever there was a situation offering visibility and free advertising, he seemed to make the most of the opportunity.

His style, theatrics, and others manners of behavior, of course, did not go unnoticed by the dental establishment, and he was constantly in legal trouble. Parker referred to his adversaries as “the ethicals” who were engaged in “the noble tooth-plumbing profession.” He seemed to relish these battles because each legal squabble produced a great deal of public notice. Of particular significance to the dental establishment was his use of advertising. Even his stage name, “Painless Parker,” was in play; when charges of false advertising were made in 1915, Parker had his first name legally changed from Edgar to Painless, and this ended the problem.

Parker’s business thrived even in the midst of continuing legal controversy, and he continued to open more dental offices, particularly in the West. His clinics were large and modern with multiple chairs (ie, more chairs than doctors). He hired dental assistants and hygienists to work his chain of clinics. He also hired many dentists to work in his offices. When he had difficulty locating dentists to work for him, he was known to help rehabilitate an alcoholic dentist and put him back to work. When he died in 1952, he had 28 offices that employed 78 dentists; he made and lost fortunes, but he died a multimillionaire from his dental businesses and large land holdings in California.

News of his death was reported in Life magazine in 1952; if Parker was not the best dentist in the world, he was certainly the most famous. He lived a life of contrasts: he was famous and infamous, a celebrity and a scoundrel, a quack and an innovator, a shameless self-promoter and a patient advocate, and a provocateur and a victim; he was admired and respected, and hated, for what he did and how he did it.

Was he an unprofessional dentist or a practitioner ahead of his time? He championed oral hygiene, preventive care, and going to the dentist. In today’s terms, he supported access to care. He was one of the first to use local anesthesia, even though it was generally considered inappropriate at the time (ether and “laughing gas” were more popular and accepted).

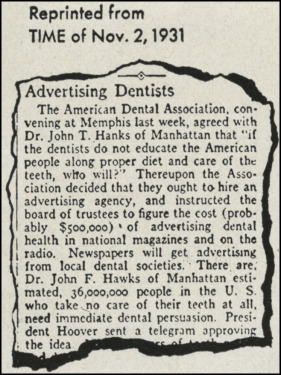

He was an astute businessman and believed in the benefits of marketing. He advertised, which, as it turns out, is common practice today. Even the American Dental Association (ADA), in 1931, concluded that the public needs to be educated through advertising (much to Parker’s delight; see the fine print in Fig 2 ), and it allocated approximately $500,000 to do so (a huge sum at the time).