A man, aged 28 years 9 months, came for an orthodontic consultation for a skeletal Class III malocclusion (ANB angle, −3°) with a modest asymmetric Class II and Class III molar relationship, complicated by an anterior crossbite, a deepbite, and 12 mm of asymmetric maxillary crowding. Despite the severity of the malocclusion (Discrepancy Index, 37), the patient desired noninvasive camouflage treatment. The 3-Ring diagnosis showed that treatment without extractions or orthognathic surgery was a viable approach. Arch length analysis indicated that differential interproximal enamel reduction could resolve the crowding and midline discrepancy, but a miniscrew in the infrazygomatic crest was needed to retract the right buccal segment. The patient accepted the complex, staged treatment plan with the understanding that it would require about 3.5 years. Fixed appliance treatment with passive self-ligating brackets, early light short elastics, bite turbos, interproximal enamel reduction, and infrazygomatic crest retraction opened the vertical dimension of the occlusion, improved the ANB angle by 2°, and achieved excellent alignment, as evidenced by a Cast Radiograph Evaluation score of 28 and a Pink and White dental esthetic score of 3.

Highlights

- •

Differential diagnosis was made with Discrepancy Index, 3-Ring, and Extraction Decision Table.

- •

Conservative treatment was feasible.

- •

Passive self-ligating brackets produced optimal results without excessive arch expansion or incisal flaring.

- •

Crossbite and deepbite were corrected with bite turbos and early light Class III elastics.

An Angle classification for malocclusion focuses on the occlusal relationship of the first molars, so it can be misleading for many malocclusions. Likewise, anterior crossbites may be deceptive, particularly when associated with a prognathic skeletal pattern and a concave face. This unusual case appears to be a modest problem based on the molar discrepancy, but it is a severe malocclusion based on the American Board of Orthodontics Discrepancy Index score of 37, as shown in Supplementary Worksheet 1 . Furthermore, the face, anterior crossbite, and ANB angle of −3° are consistent with a skeletal Class III malocclusion. Despite the severity of the problem, the patient insisted on the most conservative treatment possible, so a careful differential diagnosis was critical to determine whether a relatively noninvasive approach was indicated or even possible.

Anterior crossbites with a Class III skeletal pattern have a layer of complexity that is not readily diagnosed unless a systematic test is used such as Lin’s 3-Ring diagnosis method. A careful application of the Discrepancy Index and the 3-Ring method demonstrated that conservative treatment was feasible. However, optimal sagittal alignment of the dentition required a stainless steel miniscrew (OrthoBoneScrew; Newton’s A, Hsinchu, Taiwan) in the right infrazygomatic crest to retract the right buccal segment.

Diagnosis and etiology

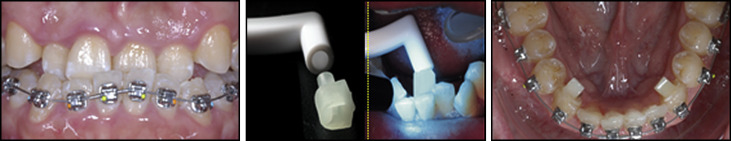

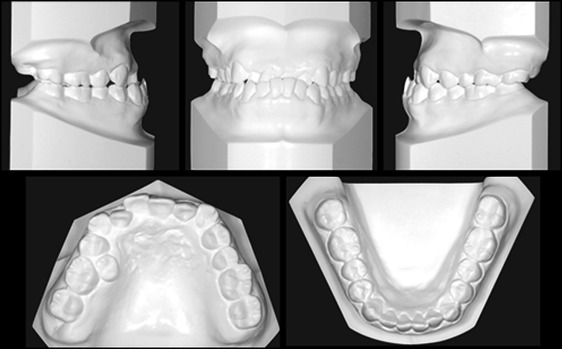

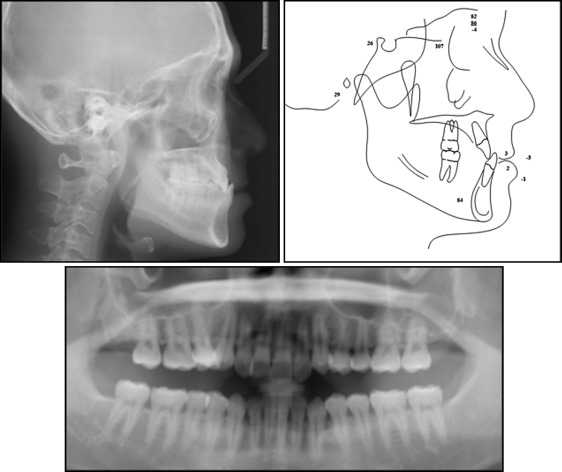

A man, aged 28 years 9 months, came for an orthodontic consultation with the following chief concerns: thin upper lip, irregular dentition, and poor smile esthetics ( Fig 1 ). There was no contributing medical or dental history. The clinical examination showed a retrusive upper lip, a deep anterior crossbite of all maxillary incisors, a posterior lingual crossbite of the maxillary right second premolar, and irregular dental attrition of the maxillary right central incisor. Overbite was 7 mm, and overjet was −3 mm. There were 12 mm of asymmetric crowding in the maxillary arch, and asymmetric Class II (right) and Class III (left) buccal segments associated with a midline deviation of the maxilla that was 3 mm to the right ( Fig 2 ). The radiographic and cephalometric surveys before treatment are shown ( Fig 3 ). The cephalometric measurements are summarized in Table I . A severely worn facet on the maxillary right central incisor required coordinated orthodontic alignment and restorative care ( Fig 4 ).

| Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal | |||

| SNA (°) | 81 | 81 | 0 |

| SNB (°) | 84 | 82 | 2 |

| ANB (°) | −3 | −1 | 2 |

| SN-MP (°) | 28 | 29 | 1 |

| FMA (°) | 23 | 24 | 1 |

| Dental | |||

| U1 to NA (mm) | 3 | 7 | 4 |

| U1 to SN (°) | 102 | 114.5 | 12.5 |

| L1 to NB (mm) | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| L1 TO MP (°) | 88 | 91.5 | 3.5 |

| Facial | |||

| E-line to UL (mm) | −5 | −4 | 1 |

| E-line to LL (mm) | −0.5 | −2 | 1.5 |

Treatment objectives

In the maxilla (all 3 planes), the objective was to maintain the anteroposterior, vertical, and transverse relationships.

In the mandible (all 3 planes), the objectives were to maintain the anteroposterior and transverse relationships and to rotate the vertical segment clockwise to improve the ANB angle.

For the maxillary dentition, the objectives were to (1) protract the incisors and retract the molars anteroposteriorly, (2) slightly increase the vertical, and (3) slightly increase the intermolar width.

For the mandibular dentition, the objectives were to (1) retract anteroposteriorly; (2) intrude the incisors vertically, and (3) maintain intermolar and intercanine widths.

For the facial esthetics, the objectives were to (1) increase the upper lip protrusion and (2) increase the vertical dimension of the occlusion to achieve an orthognathic profile.

Treatment objectives

In the maxilla (all 3 planes), the objective was to maintain the anteroposterior, vertical, and transverse relationships.

In the mandible (all 3 planes), the objectives were to maintain the anteroposterior and transverse relationships and to rotate the vertical segment clockwise to improve the ANB angle.

For the maxillary dentition, the objectives were to (1) protract the incisors and retract the molars anteroposteriorly, (2) slightly increase the vertical, and (3) slightly increase the intermolar width.

For the mandibular dentition, the objectives were to (1) retract anteroposteriorly; (2) intrude the incisors vertically, and (3) maintain intermolar and intercanine widths.

For the facial esthetics, the objectives were to (1) increase the upper lip protrusion and (2) increase the vertical dimension of the occlusion to achieve an orthognathic profile.

Treatment alternatives

After a careful evaluation of the patient’s problems, we proposed 3 tentative treatment plans. Treatment plan A was extraction of the maxillary second premolars and the mandibular first premolars. Treatment plan B was insertion of 2 miniscrews in the buccal shelf of the mandible to retract the entire arch. Treatment plan C was nonextraction camouflage treatment using Class III elastics to retract the mandibular labial segment and protract the maxillary labial segment. The patient chose the most conservative option: treatment plan C. However, this relatively noninvasive approach required extensive interproximal reduction of the anterior maxillary arch and an orthodontic bone screw in the infrazygomatic crest to retract the right buccal segment. The patient was informed that this conservative approach would require 3 to 4 years of treatment, primarily because of the sequence of procedures necessary to resolve 12 mm of asymmetric crowding in the maxillary arch, without extracting any teeth. He accepted this treatment limitation.

The final plan included the following: (1) no extractions or orthognathic surgery; (2) Damon Q brackets (Ormco, Glendora, Calif): standard torque passive self-ligating brackets bonded upside-down on the maxillary canines, lateral incisors, and central incisors to resist the flaring effect of Class III elastics; (3) open-coil springs between the maxillary right first molar and first premolar, and between the maxillary right canine and central incisor for opening space to relieve crowding; (4) bite turbos on the mandibular canines initially and then on the mandibular central incisors as the bite opened; (5) Class III early light short elastics to assist with anterior crossbite correction and to open the vertical dimension of the occlusion; (6) an OrthoBoneScrew in the right infrazygomatic crest to retract the right buccal segment; and (7) restoration of the maxillary right central incisor with a porcelain veneer or composite resin.

Treatment progress

The 0.022-in slot Damon Q standard torque brackets were bonded on the mandibular arch. Bite turbos were bonded on the lingual surfaces of mandibular canines to open the bite and facilitate anterior crossbite correction ( Fig 5 ). One month later, the maxillary arch was bonded with standard torque brackets, but those on the 6 maxillary anterior teeth (canine to canine) were bonded upside-down to deliver negative torque ( Table II ). Initially, there was inadequate space to bond the maxillary right second premolar and the lateral incisor, so open-coil springs were placed on the archwire, and those teeth were bonded with upside-down, standard torque brackets as soon as adequate space was available. The lengths of the active nickel-titanium springs were extended approximately 2 mm to activate space opening. The maxillary right central incisor was severely worn, with dentin exposure. The amount of lost tooth structure was estimated to be about 2 mm in the axial dimension, so the bracket position for the maxillary left central incisor was 6 mm from the incisor edge, and the corresponding distance for the maxillary right central incisor was only 4 mm ( Fig 6 ). The goal was to achieve optimal gingival alignment and then restore the maxillary right central incisor tooth structure as needed. The initial archwires were 0.014-in copper-nickel-titanium. Class III early light short elastics (Quail, 3/16-in, 2 oz; Ormco) were placed from the mandibular first premolars to the maxillary first molars, and bite turbos were bonded on the lingual surfaces of the mandibular central incisors ( Fig 7 ). The stepwise opening of the bite with bite turbos was for patient comfort. The patient was instructed to wear the 2-oz early light short elastics full time and to replace them with new ones at least 4 times per day, preferably after meals or snacks. By the fifth month of treatment, the anterior crossbite was corrected ( Fig 8 ), the bite turbos were removed, and the mandibular archwire was changed to 0.014 × 0.025-in copper-nickel-titanium. In the seventh month, the maxillary archwire was changed to 0.014 × 0.025-in copper-nickel-titanium. Drop-in hooks (Ormco) were fitted into the vertical slots of the maxillary canine brackets to secure the Class II elastics (Fox, 1/4-in, 3.5 oz; Ormco), which accomplished anteroposterior correction while promoting development of the smile arc. The change from Class III to Class II elastics at 7 months ( Fig 7 ) was necessary because of the opening of the bite and the 2° improvement in the ANB angle.