We report on the successful treatment of a 32-year-old woman with condylar hyperplasia and severe mandibular crowding. In addition, her maxilla was canted to the right, her mandibular midline and chin point deviated to the left, and her maxillary canines were missing. The treatment plan included (1) aligning and leveling the teeth in both arches, (2) correcting overbite and overjet, (3) performing LeFort I osteotomy and bilateral split osteotomies, and (4) correcting the malocclusion postsurgically. The orthodontic treatment was performed with custom lingual braces and clear brackets, and virtual surgical planning techniques were used to plan the orthognathic surgery. The condylar hyperplasia and the mandibular crowding were corrected. At the end of treatment, the patient’s face appeared symmetrical. The results suggest that esthetic and functional results can be achieved with the cooperation of 2 specialties and the use of state-of-the-art technology.

Highlights

- •

A woman had progressive condylar hyperplasia from age 3 years.

- •

Three-dimensional diagnosis and treatment plan were conducted.

- •

A self-ligating lingual brace system were used.

- •

Three-dimensional surgery was performed and splints placed to correct facial asymmetry.

Condylar hyperplasia (CH) is characterized by overgrowth of the condylar head and neck and the ramus unilaterally. The overgrowth results in deviation of the chin to the contralateral side, with subsequent results in the occlusion and facial symmetry. The etiology of this rare condition is not clearly defined yet, and there are only assumptions of the factors causing CH. Diagnosis of CH is often based on clinical findings, radiographic results, photographs, and cast analysis. To plan effective treatment, it is essential to determine the type of CH and whether the condition is progressive. Definitive treatment includes orthognathic surgery for the correction of the skeletal deformity and orthodontics for establishing a proper occlusion.

In this case report, we describe the innovative, comprehensive treatment of an adult patient with unilateral CH and severe mandibular crowding. See Supplemental Materials for a short video presentation about this study.

Diagnosis and etiology

In November 2011, a 32-year-old woman came to the Department of Orthodontics at the University of Birmingham in Alabama with the chief complaint of facial asymmetry. She had grown normally until the age of 3, when she suffered a fracture of the condyle. The fracture was treated conservatively, and she developed a noticeable facial growth disturbance as she matured. She also had difficulty in chewing and experienced frequent muscle spasms.

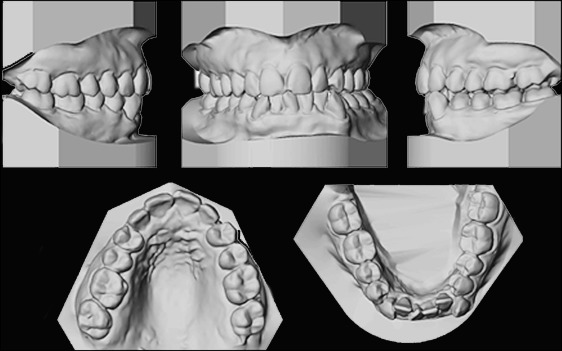

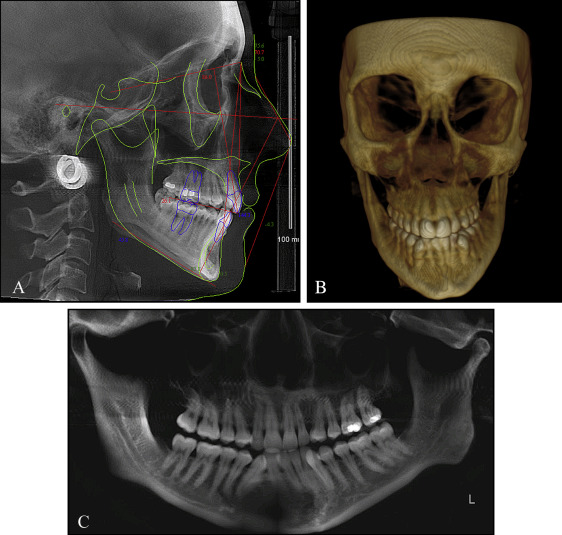

When facial asymmetry is suspected, the first step is to conduct thorough extraoral and intraoral examinations. At the records appointment, impressions of the maxillary and mandibular jaws were taken, and a facebow was used. A tongue depressor was also used to help evaluate the situation. The clinical findings were highly indicative of structural involvement of the right temporomandibular joint, so cephalometric and panoramic radiographs were acquired. Furthermore, a cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan, a 3dMD (Atlanta, Georgia) image, and intraoral and extraoral pictures were taken on that day to complete the records ( Figs 1-3 ).

Extraorally, the patient’s facial profile was convex, and the nose and the lips were normal. The diagnosis included right condylar hyperplasia, maxillary canting with the right side down (because the maxilla followed the mandible), and chin point deviation of 5 mm to the left. The lower third of the face appeared to be increased. Intraorally, the patient had severe mandibular crowding, the mandibular midline was shifted 4 mm to the left (the maxillary midline was normal), and the maxillary canines were missing. The right side was a Class II (one half) malocclusion, and the left side was a full Class II malocclusion. Overjet was 3.5 mm, and overbite was –0.8 mm.

Treatment plan

The patient was diagnosed with CH, right maxillary canting, deviation of the mandibular midline to the left, chin point deviation to the left, missing maxillary canines, severe mandibular crowding, and a Class II malocclusion. Based on the diagnostic records and consultation with the patient, the following plan was developed: (1) align and level the teeth in both arches, (2) correct overbite and overjet, (3) close spaces, (4) perform bimaxillary surgery, and (5) treat the malocclusion after the surgery.

Treatment plan

The patient was diagnosed with CH, right maxillary canting, deviation of the mandibular midline to the left, chin point deviation to the left, missing maxillary canines, severe mandibular crowding, and a Class II malocclusion. Based on the diagnostic records and consultation with the patient, the following plan was developed: (1) align and level the teeth in both arches, (2) correct overbite and overjet, (3) close spaces, (4) perform bimaxillary surgery, and (5) treat the malocclusion after the surgery.

Treatment progress

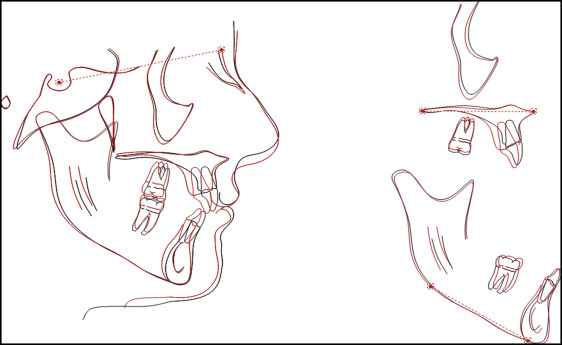

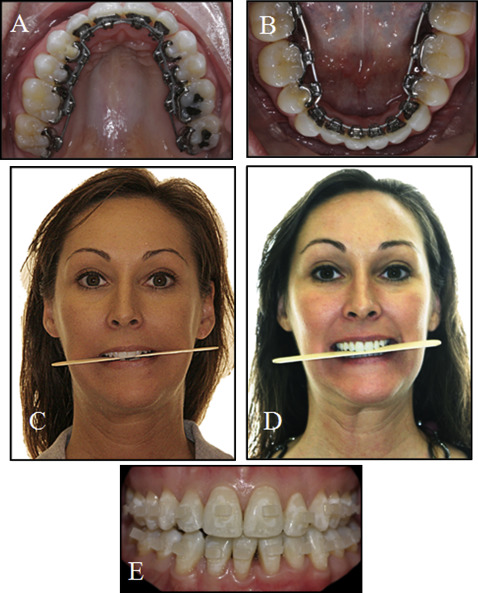

The first step of the treatment plan included the extraction of the mandibular first premolars to create the space needed for the upcoming movements. After the extractions, a self-ligating lingual appliance (Harmony System, Paris, France) was used; it satisfied the patient’s desire for an esthetic approach. Indirect bonding in the mandible proved to be challenging because of the crowding. After 1 month, buttons were placed on the mandibular canines and second premolars to achieve the retraction of the canines. After that, the rest of the mandibular teeth were bonded, and routine orthodontic treatment was performed. A power chain was used to derotate the mandibular right central incisor ( Fig 4 ). About 22 months after the initial bonding, 2-jaw surgery was scheduled. Impressions of both arches were taken, and 3dMD images and CBCT scans were acquired. All the information was forwarded to Medical Modeling (Golden, Colo). A cephalometric radiograph was acquired, and it was superimposed on the initial cephalometric radiograph ( Fig 5 ). Before surgery, clear attachments and buttons were placed on the mandibular and maxillary teeth for the postoperative orthodontic treatment ( Fig 6 ). Twenty-five months after the initiation of the orthodontic treatment, the patient was ready for the surgical operation.

The surgical treatment plan included a LeFort I osteotomy and bilateral sagittal split osteotomies using virtual surgical planning by Medical Modeling. For determining the kind of movements to perform in the maxilla, a key point had to be selected. The plan was not to age the patient by intruding the posterior segment. Also, the position of the maxillary left central incisor was ideal. So it was decided to perform maxillary movements in the 3 planes of space to correct the maxillary position, based on the maxillary molars. The final position of the mandibular dentition would be based on the position of the maxilla. Furthermore, it was decided not to change the maxillary midline. On the other hand, A-point was moved 2.04 mm to the left, B-point was moved 5.00 mm to the right, and pogonion was moved 7.04 mm to the right. The virtual planning workflow enabled visualizing the final result. Intermediate and final positions of the maxilla and the mandible were presented in detail, and a soft tissue simulation was acquired as well ( Fig 7 ). A LeFort I osteotomy was performed with reduction of the right posterior maxilla to allow a 2-mm impaction of the right side. An intermediate surgical splint fabricated by Medical Modeling was used to position the maxilla for fixation. Two 1.5-mm, L-shaped titanium plates (KLS Martin, Jacksonville, Fla) were used bilaterally at the zygomatic buttress and piriform aperture. Next, bilateral sagittal split osteotomies were completed with rotation of the mandible to the right for correction of the mandibular asymmetry. The final surgical splint was used to ensure a proper maxillomandibular relationship before placing fixation for the mandibular osteotomies. One 2.00-mm monocortical titanium plate (KLS Martin) was used bilaterally. The final occlusion was verified and found to be satisfactory and repeatable with the splint removed ( Fig 8 ). Light guiding elastics were placed, and the patient was extubated without complication. She was admitted to the floor for postoperative observation and subsequently discharged on postoperative day 1 after an uneventful hospital course. She was given several medicines that are routine after orthognathic surgery. She received Percocet (Tylenol [Johnson and Johnson, New Brunswick, New Jersey] plus oxycodone; Stat Rx, USA LLC) and straight oxycodone for pain, and amoxicillin for the antibiotic. For decongestants, she received Afrin nasal spray, saline solution nasal spray, pseudoephedrine, and guaifenesin. She received Phenergan for nausea and vomiting. All of these medications are standard after this type of surgery.