Chapter 4

Community Health Centers

OVERVIEW

The 2012 election is in the rearview mirror and the endless debate about the status of the Accountable Care Act (ACA) has ended. It is here to stay and will expand coverage to 32 million individuals in 2014, half through Medicaid expansion and half through health insurance exchanges with safety-net providers granted most-favored-nation status. States like California that are actively implementing insurance exchanges are trying to get more people covered, conducting value-based purchasing to encourage delivery reform and expanding the safety-net delivery system. There is no better time to be talking about the value of safety-net clinics (also known as Community Health Centers) because they are an ideal model for primary care reform in this country. The good news is the ACA has made money available for the development and expansion of community health centers; thus, looking at ways to optimize this model of care is definitely worthwhile.

Safety-net clinics, by definition, serve the underserved, underinsured, uninsured, migrant workers, and undocumented immigrants. Occasionally an individual community health center is able to attract individuals covered by insurance who choose to use that facility because of the comprehensive care, the coordination and collaboration among providers, ease of access, and attention to the whole person. As an example, Adelante Healthcare in Phoenix, at two of its locations, is able to draw patients from a nearby Sunbelt retirement community because of its outstanding clinical care, as well as the comfortable and attractive design of its facilities. This change in payer mix helps to subsidize uncompensated care and sliding fee discounts made for low-income individuals who are unable to pay full fee for their care.

There is a fundamental restructuring of primary care occurring in the United States and it is largely focused on the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH), which is a foundational piece of the Accountable Care Organization (ACO). The onslaught of patients who will have coverage through the ACA may not have access unless a fundamental shift in care management occurs. Valuable lessons can be learned from the approach to holistic care at two ends of the spectrum—safety-net community health centers and physicians who practice membership-based direct care, sometimes referred to as “concierge care,” the latter are discussed in Chapter 3. Both achieve a high level of continuity of care, create a medical home for patients, and offer prompt access and coordination of care for patients who have chronic or complex medical conditions. The ACA will ramp up the need for primary care and the deployment of many more community health centers and ambulatory care facilities, but the physical design and clinical workflow will be distinctly different from existing models. Clearly the focus is on wellness, management of chronic conditions, team-based care delivery, an optimized and personalized patient experience, and measurement of performance in health outcomes. Experiments are going on around the nation as physicians try to respond to the new normal of reduced reimbursement, the steady increase and complexity of chronic disease management, the focus on prevention, and the tsunami of newly insured patients heading their way. It’s an exciting time to be working in healthcare as it is reshaped and reformed in ways that will hopefully achieve the Triple Aim of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement:

- Improving the patient experience

- Improving the health of populations

- Reducing the per capita cost

Community health centers are an efficient and practical model for the delivery of health and wellness. The coordination of care and collaboration among a team of clinicians (see Figures 3-15, 3-16, 3-17, and 4-21) enable patients to receive a multidisciplinary assessment with a focus on prevention and wellness. The goal is to provide as much care as necessary at each visit. Behavioral health is often included in these settings because approximately 70 percent of patients require it. If they are referred out, they often do not return. Dental care is also frequently found. It may not be widely known but a large number of patients report to emergency departments for a dental abscess or other problems arising from lack of dental care until an extreme condition arises. An ED cannot help these individuals, they can only treat the pain which is a very temporary fix. Poor dental care leads to serious periodontal disease that can cause severe heart damage and other health problems.

It is interesting that the redesign of primary care in the United States is looking a lot like that of community health centers. Refer to Chapter 1 for a discussion of the report The Building Blocks of High-Performing Primary Care: Lessons from the Field, published by the California HealthCare Foundation, which is a very detailed and specific guide to improving primary care based on a study of seven high-performance primary care centers, five of which were community health centers. The entire report can be downloaded from www.chcf.org (see the “Resources” sidebar later in this chapter).

Features of community health centers that make them unique are:

- Comprehensive care at one location

- Patient navigator for referrals to subspecialists and community resources

- Same-day access; do as much as possible in one visit

- Continuity of care; proactive management and follow-up

- Team collaboration with each professional working to the limit of their license

- Focus on wellness and prevention (nutrition counseling, cooking classes, exercise programs, chronic disease group visits)

Characteristics of “Safety-Net” Community Health Centers

Community health centers are an efficient model of care because they treat the whole person and focus on continuity among a multidisciplinary group of providers that may include physicians, physician assistants, nurses, nurse practitioners, behavioral health specialists, nutritionists, dentists, pharmacists, social workers, and navigators who coordinate specialist care and connect patients to community outreach programs. This is very different from the episodic care that characterizes most primary care visits today. This care model has a proactive focus in terms of following up with patients and, once they arrive for an appointment, making sure the patient is up to date on vaccinations, required diagnostic tests, prescriptions, annual gynecological exams, and even dental exams and hygiene. It is characterized by collaborative team care that leads to more informed decision making, and this has space plan implications to be discussed later. There is a focus on accommodation of family in exam rooms and in consultation spaces and the need to make children feel welcome with appropriate artwork and play activities in waiting areas. There is a high priority to influence patients by educating them about good nutrition, cessation of smoking, and making lifestyle changes that will create better health. There may be cooking classes or demonstrations, an onsite vegetable garden to teach children how vegetables are grown, or a weekly farmers market to bring fresh produce to neighborhoods that are poorly served by supermarkets. The overall goal is to provide patients with a very personalized healthcare experience, one in which they are an active participant in decision making.

Community health centers may be small (5,000 square feet) or large enough to accommodate the full range of services: family medicine, pediatrics, OB/GYN, dental care, internal medicine, dermatology, ENT, podiatry, pharmacy, audiology, speech therapy, café, nutrition, lab, radiology, and community meeting rooms. By virtue of having little money to devote to facility construction and design, safety-net clinics have often been cobbled together with donated materials and whatever was available at the lowest cost. In recent years; however, a number of imaginatively designed facilities have opened that use color, lighting, and attractive exterior design to enhance the patient experience and many of these are even LEED® certified. Design practitioners are also applying evidence-based principles to the design of these facilities.

Patient-Centered Medical Homes

A fundamental aspect of primary care reform is the creation of patient-centered medical homes. The concept actually parallels in a more formal way the characteristics of safety-net health centers in terms of delivery of care. To be designated a PCMH according to Transformed CEO, Terry McGeeney, “primary care practices are expected to provide comprehensive primary care including care management, care coordination, enhanced access, patient engagement, and proactive patient planning and are expected to be NCQA (National Committee for Quality Assurance Level 3 or an equivalent (i.e., complete medical homes) and meaningful use certified.” (This statement was downloaded from transformed.com/ceoreports/comprehensive_primary_care_initiative.cfm. accessed October 2, 2013.)

In 2007 leading primary care associations endorsed the Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home as a goal for the organization and delivery of care throughout the healthcare system. It requires a high level of information technology, provider payment reform that rewards outcomes, and team-based education and training of the health professions workforce (pcpcc.net/what-we-do). In 2008 the Commonwealth Fund launched the five-year Safety-Net Medical Home Initiative to help 65 community health centers transform into patient-centered medical homes. In 2010 the ACA included substantial support for medical home initiatives, including the CMS Advanced Primary Care Practice Demonstration, bringing together for the first time public and private health plans to examine the effectiveness of medical homes. As of January 2012, 41 states had adopted medical home programs; however, they structure their definitions and priorities differently. In some states, payments to providers may vary depending on the number of chronic conditions a patient has and if there is a language barrier or mental illness. In other states, payments are based on a maximum per member per month that varies with the payer type (Medicare Advantage Plans, Medicaid, commercial payers) and may vary based on medical home effectiveness. A state may pay primary care providers for remote consultations with hospital-based specialists to improve care for complex patients or they may receive funding for establishing a registry for tracking important patient data to develop a system for sharing clinical information perhaps with a key hospital.

Some community health centers are considered Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC), which is a reimbursement designation from the Bureau of Primary Health Care and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. These health centers serve a variety of medically underserved populations with some receiving special funding to provide services to migrant and seasonal agricultural workers or residents of public housing, or to offer healthcare for the homeless programs.

There are various accreditation agencies for PCMH each with a set of standards and specific criteria. The Joint Commission, in 2011, launched the Primary Care Medical Home Certification option for its accredited ambulatory care organizations. In addition, the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC) offers accreditation for medical homes. There is the National Center for Medical Home Implementation Accreditation and the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) PCMH Recognition designation, which has three levels of achievement.

Financial Benefits of Medical Homes

Leading insurance payers, such as WellPoint and United Healthcare, expect that PCMHs have the potential to save twice as much as they cost with estimates of 70 percent reduction in ED visits and 40 percent lower hospital readmissions. See the tables in the noted source for outcome measures for several of the 41 states engaged in PCMH demonstration projects.1 In addition, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (www.ahrq.gov/research/primarix.htm) awarded, in 2010, 14 two-year “transforming primary care” grants to selected organizations to study the transformation of primary care practices to PCMHs. A description of each project’s diverse objectives can be found on the AHRQ Web site (www.ahrq.gov/research/transpcaw.htm).

An Evidence-Based Approach to Safety-Net Clinic Design

The Center for Health Design, in recognizing the importance and role of safety-net clinics in 2011, funded by a grant from the California HealthCare Foundation, published five white papers on various aspects of clinic design available for download on the CHD website (healthdesign.org):

- Promising Practices in Safety-Net Clinic Design (Overview)

- Designing Safety-Net Clinics for Flexibility

- Designing Safety-Net Clinics for Cultural Sensitivity

- Improving the Patient Experience

- Designing Safety-Net Clinics for Innovative Care Delivery Models

This was followed by development of a Clinic Design module on their website that, among other things, features exemplary facilities, videos, and PowerPoint slides from several regional learning collaboratives. One of the most helpful areas of the clinic design module is the interactive Design & Construction Process Toolkit, which enables one to review various recommendations at each stage of the design process, while the Cost-Benefit Analysis Tool allows one to determine the probable cost of a number of variables such as the number and size of exam rooms, cost of staffing, increases or decreases in clinic size, the cost-benefit of green design features, and more. One can enter the size of a waiting room space and find out how many seats it will accommodate or model different options of parking lot lighting to evaluate the cost of different types of lamps. This tool is found on the Clinic Design site under “MySNC.”

The question is: Does design of the built environment have the same importance in a community health center as we know it to have in other settings that mostly serve patients who have insurance? According to healthcare futurist Ian Morrison, facilities can be a service competitiveness differentiator if you have to “earn” the newly covered individuals. The quality of the environment sends a powerful message to patients and staff about how they are valued and respected. Patients receiving care in a comfortable and attractive environment that respects their privacy and dignity are apt to be more receptive to suggestions for improving their health and perhaps even be more compliant with medications and follow-up appointments. They may actually look forward to return visits and view the health center as a place to receive education, to join groups for management of chronic conditions, and as a link to community resources. And we know that good design supports quality and patient safety; it makes it easier to do things right.

Overall Considerations

- Aim for 90 percent of spaces having natural light through windows, clerestories, Sonotubes, and skylights (Figures 4-1 and 4-2).

Figure 4-1. Corridor in community health center displays photographic art taken by children in the community. Grace Hill Neighborhood Health Center—Water Tower, St. Louis, Missouri.

(Architecture and Interior Design by Arcturis; Photographer: Sam Fentress)

Figure 4-2. Team collaboration area of community health center. Hennepin County Medical Center’s Whittier Clinic, Minneapolis.

(Courtesy of HGA Architects and Engineers) - Study the demographics of the population served to understand customs, cultural preferences, levels of literacy, and to be able to develop a color palette and design concept that resonates for that community (see Color Plate 7, Figures 4-3 and 4-4).

Figure 4-3. Vibrant lobby of community health center, West County Health Center, Richmond, California.

(Architecture and Interior Design by Hawley Peterson Snyder; Photographs by David Wakely)

Figure 4-4. Exterior of La Maestra Community Health Center is an expression of the multicultural community it serves.

(Photo courtesy of Richard Yen & Associates, Architects and Planners) - Avoid jogs in circulation paths that make it difficult to see department entries. If space planning is well executed, wayfinding requires little signage (Figure 4-5 and Color Plate 8, Figures 4-6, 4-7, and 4-10).

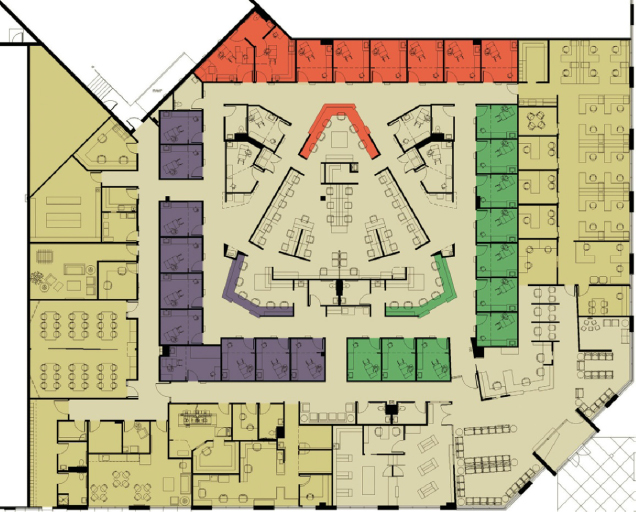

Figure 4-6. Space plan community health center incorporating intuitive wayfinding. Note team collaboration center in core, 21,975 square feet, University of Minnesota Physicians Smiley’s Clinic, Minneapolis.

(Courtesy of HGA Architects and Engineers; Photographer: Saari Forrai Photography)

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses