The search for the ideal method of treatment for mandibular fractures has continued for thousands of years. These injuries have unique and problematic features for adequate reliable wound healing. Oral and maxillofacial surgeons must learn and master several techniques for mandibular fracture treatment. The age-old successful management of these injuries using closed reduction techniques always should be considered when mandibular trauma presents. The closed reduction remains a mainstay of mandibular fracture treatment. An adequate knowledge of anatomy, multiple closed reduction techniques, and the physiology of fracture healing must be adequately understood and technically mastered by the oral and maxillofacial surgical team for the present and future of mandibular fracture management.

Definition

Closed reduction of mandibular fractures can be defined as the treatment of fractured segments without visualization through skin or mucous membranes. There are many differing methods to achieve closed reduction; however, all of these techniques share the common application of materials that ideally prevent movement of bony segments during the healing phase. The most critical and necessary factors in management of any fracture are reduction and stabilization of the fracture, which should be accomplished by the simplest means possible to achieve optimal results. Considering these statements, “closed reduction” continues to be used extensively in the successful management and treatment of all types of mandibular fractures.

When treating mandibular fractures, surgeons must attempt to return patients to as close to a state of normal function and appearance as possible. Considering the anatomic and functional relationship of the maxilla and mandible, the thin soft-tissue covering of the bony structures, the dentition and its bacterial exposure, and the essential need for the oral cavity with regard to caloric intake and survival necessity, fracture management of this area of the body remains unique among all other bones of the body.

History

Any academic discussion of mandibular fracture treatment should include an historical review. When we consider that open reduction techniques are relatively new (only used within the past few decades), we should consider that management of mandibular fractures using closed reduction techniques has occurred for centuries. Mandibular fractures have been traced back by paleontologists to the age of Neanderthals; however, the ancient Egyptians (circa 1700 bc ) were the first to detail the diagnosis and prognosis of the mandibular fracture. At that time, fracture management was considered impossible. Hippocrates, the “father of medicine” (circa 430–370 bc ), wrote on the subject of mandibular fractures in the Corpus Hippocraticum, a collection of approximately 70 writings detailing his teachings. Hippocrates’ writings included extensive descriptions of the need for stabilization of fractures to lead to consolidation. He is said to be the first to advocate the use of gold wire—or linen thread if wire was unavailable—to maintain proper position of the fractured segments. Fracture management at that time most often involved bandaging techniques, which Hippocrates noted were suboptimal without adequate reduction of fractured segments.

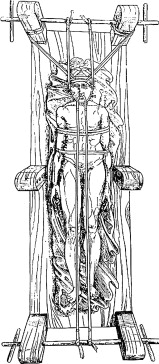

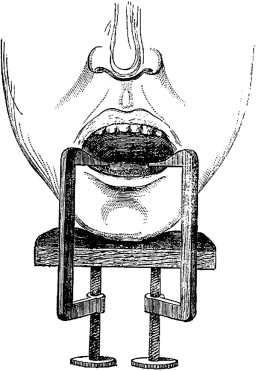

Throughout the past centuries, many surgeons, such as John Bernhardt Erich, Harold Gillies, Thomas Gilmer, Stout, Robert Henry Ivy, Varaztad Kazanjian, T.B. Gunning, Norman W. Kingsley, and many others attempted, to successfully treat fractures with wiring, splints, and intraoral and extraoral appliances ( Figs. 1, 2 ). Each person contributed innovative and cutting edge methods of treating mandibular fractures for his or her era. The use of intermaxillary fixation (IMF), which became popular in the mid-1800s, led to the development of our current methods of treating mandibular fractures. The ideal of returning the patient to the proper occlusal relationship was—and still remains—the basis for all mandibular fracture treatment in the dentate patient.

History

Any academic discussion of mandibular fracture treatment should include an historical review. When we consider that open reduction techniques are relatively new (only used within the past few decades), we should consider that management of mandibular fractures using closed reduction techniques has occurred for centuries. Mandibular fractures have been traced back by paleontologists to the age of Neanderthals; however, the ancient Egyptians (circa 1700 bc ) were the first to detail the diagnosis and prognosis of the mandibular fracture. At that time, fracture management was considered impossible. Hippocrates, the “father of medicine” (circa 430–370 bc ), wrote on the subject of mandibular fractures in the Corpus Hippocraticum, a collection of approximately 70 writings detailing his teachings. Hippocrates’ writings included extensive descriptions of the need for stabilization of fractures to lead to consolidation. He is said to be the first to advocate the use of gold wire—or linen thread if wire was unavailable—to maintain proper position of the fractured segments. Fracture management at that time most often involved bandaging techniques, which Hippocrates noted were suboptimal without adequate reduction of fractured segments.

Throughout the past centuries, many surgeons, such as John Bernhardt Erich, Harold Gillies, Thomas Gilmer, Stout, Robert Henry Ivy, Varaztad Kazanjian, T.B. Gunning, Norman W. Kingsley, and many others attempted, to successfully treat fractures with wiring, splints, and intraoral and extraoral appliances ( Figs. 1, 2 ). Each person contributed innovative and cutting edge methods of treating mandibular fractures for his or her era. The use of intermaxillary fixation (IMF), which became popular in the mid-1800s, led to the development of our current methods of treating mandibular fractures. The ideal of returning the patient to the proper occlusal relationship was—and still remains—the basis for all mandibular fracture treatment in the dentate patient.

Classification as favorable versus unfavorable

The classification of mandibular fractures into a favorable versus unfavorable category is a product of muscular force and potential displacement of the segments. The muscle groups that may impact the favorability of a fracture include the retractors, protrusors, elevators, and depressor-retractors groups ( Fig. 3 ). Each muscle group exerts specific and significant force patterns that can displace segments and make closed reduction techniques obsolete if the segments cannot be reduced and stabilized against the forces of the muscular pull.

Although the mandible can fracture essentially in any area, each with unique anatomy and potential muscular action displacing segments shown in Fig. 3 , a discussion of angle fractures helps to review the concept of favorable versus unfavorable and the associated terminology. The unique anatomy in the area of the ramus/angle includes the insertion of the muscles of mastication, the temporalis, masseter, lateral, and medial pterygoid muscles, and the mylohyoid. The muscles continue to exert forces on the fractured segments to which they attach. In situations in which muscle action displaces the segments, the fracture is considered “unfavorable.” If muscle action tends to the pull the segments together, it is considered “favorable.” Because of the differential muscle action, further consideration must be given to horizontal or vertical favorability. In general, the pterygomasseteric sling displaces the segments in an angle fracture medially and superiorly in an unfavorable fracture pattern ( Fig. 4 A–D). Closed reductions in the case of the unfavorable angle fracture may be complicated because the fixation method may not be rigid enough to counteract the medial and superior pull of the muscle sling, leading to proximal segment displacement, malunions, and nonunions. When angle fractures are classified as and considered to be favorable, muscle action actually helps to bring the segments into contact, and these fractures are more amenable to closed reduction techniques.

Techniques for closed reduction

Erich arch bars are the most commonly used devices in closed reduction techniques; closed reduction is often considered synonymous with arch bar application. Arch bars provide a means of securing a stable, preinjury occlusion and allow for different force vectors to be applied if necessary to reduce the fracture and achieve the most stable position for healing.

Arch bar application is relatively fast and easy. It can be performed with local anesthesia, which makes it possible to use in the emergency department, clinic, or office setting. The procedure should begin with a measurement of the length of the arch bar for the mandibular and maxillary arches. Arch length ideally should be from first molar to first molar but may deviate based on fracture location, stability, reduction, and posterior occlusion. Once ideal arch bar length has been determined and the arch bars cut to length, they are secured with stainless steel wires to the maxillary and mandibular facial/buccal cervical levels of the teeth. Stainless steel wires are traditionally 24 or 26 gauge wire and are often prestretched. Maxillary and mandibular lug position on the arch bars should be checked before passing and securing wires. The occasional inverted arch bar can significantly lengthen the procedure when it requires removal and replacement in the correct position. The wire space between the lug and the base of the arch bar should be open toward the apices of the teeth ( Fig. 5 ).