Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

The current state of the art in reconstruction focuses on the use of recombinant hormones, stem cells, and scaffolds, with the goal of tissue regeneration. Although these technologies and techniques are surely the way of the future, bone grafting continues to play a primary role in the field of oral and craniomaxillofacial surgery.

The character of bone grafts harvested from different donor sites or derived from different germ cell layers and the behavior of these grafts when placed in different recipient sites have been a topic of much debate. Researchers and surgeons such as Wolff, Moss, Enlow, Whitaker, Axhausen, Boyne, Longaker, and Marx have all helped elucidate the details of bone graft healing; the importance of the interaction between bone and recipient soft tissue throughout the bone grafting process also has been highlighted.

The “ideal” bone graft is difficult to identify due to the number of clinical scenarios that may require various combinations of onlay, inlay, block, and particulate grafts. A donor site that is readily available with ample volume, easily harvested without significant morbidity, and able to satisfy many different indications is as close to “ideal” as can be achieved. The calvarial bone graft, applied through different techniques, can fulfill most bone grafting requirements in the craniomaxillofacial skeleton.

In 1890, both Mueller and Koenig published on the use of the calvaria as a pedicled osteocutaneous flap for cranial defect reconstruction. This technique was popular until 1903, when von Hacker simplified the technique by taking the outer table pedicled on only pericranium. The use of cranial bone as a free graft subsequently was described by Keen, Sohr, and Axhausen. This began a shift from allogeneic to autogenous cranial reconstruction, as described by Cushing in 1908. Further experience was gained from treatment of the many ballistic injuries that occurred during World War I and World War II. These injuries were increasingly reconstructed using calvarial grafts, as reported by Delageniere and Virenque, respectively. Calvarial grafts were applied to craniofacial reconstruction and widely championed by Paul Tessier through the 1960s and 1970s. Since his landmark publication in 1982, the cranial bone graft has become a staple in the armamentarium of maxillofacial surgeons around the world.

History of the Procedure

The current state of the art in reconstruction focuses on the use of recombinant hormones, stem cells, and scaffolds, with the goal of tissue regeneration. Although these technologies and techniques are surely the way of the future, bone grafting continues to play a primary role in the field of oral and craniomaxillofacial surgery.

The character of bone grafts harvested from different donor sites or derived from different germ cell layers and the behavior of these grafts when placed in different recipient sites have been a topic of much debate. Researchers and surgeons such as Wolff, Moss, Enlow, Whitaker, Axhausen, Boyne, Longaker, and Marx have all helped elucidate the details of bone graft healing; the importance of the interaction between bone and recipient soft tissue throughout the bone grafting process also has been highlighted.

The “ideal” bone graft is difficult to identify due to the number of clinical scenarios that may require various combinations of onlay, inlay, block, and particulate grafts. A donor site that is readily available with ample volume, easily harvested without significant morbidity, and able to satisfy many different indications is as close to “ideal” as can be achieved. The calvarial bone graft, applied through different techniques, can fulfill most bone grafting requirements in the craniomaxillofacial skeleton.

In 1890, both Mueller and Koenig published on the use of the calvaria as a pedicled osteocutaneous flap for cranial defect reconstruction. This technique was popular until 1903, when von Hacker simplified the technique by taking the outer table pedicled on only pericranium. The use of cranial bone as a free graft subsequently was described by Keen, Sohr, and Axhausen. This began a shift from allogeneic to autogenous cranial reconstruction, as described by Cushing in 1908. Further experience was gained from treatment of the many ballistic injuries that occurred during World War I and World War II. These injuries were increasingly reconstructed using calvarial grafts, as reported by Delageniere and Virenque, respectively. Calvarial grafts were applied to craniofacial reconstruction and widely championed by Paul Tessier through the 1960s and 1970s. Since his landmark publication in 1982, the cranial bone graft has become a staple in the armamentarium of maxillofacial surgeons around the world.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

The cranium provides a versatile stock of bone that can be used for autogenous grafting, and it has a number of advantages over other common harvest sites, such as the ilium, rib, or tibia. Numerous characteristics make the cranium an ideal source for meeting a number of different oral and craniomaxillofacial needs. The skull is readily included in the primary surgical field, and access is quickly and easily achieved through the scalp. With proper positioning and technique, the risk of visible scarring is negligible. A large volume and surface area of bone, with variable contour, is then available. The high proportion of cortical bone makes the outer cortex an ideal bone graft for onlay purposes. Through wide exposure, significant diploë can also be harvested and combined with morselized cortical bone for particulate grafting. Full-thickness harvest with immediate site reconstruction provides a source of thick bone for significant augmentation or reconstruction. There is limited postoperative donor site morbidity from all of these techniques. The following sections discuss specific indications for the cranial bone graft.

Cranial Vault Reconstruction

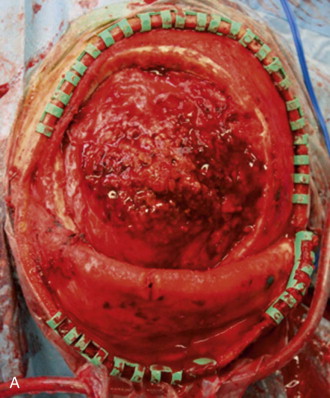

Patients who have undergone craniectomy for decompression, tumor ( Figure 125-1 ), trauma, congenital deformity, or infection may present with full-thickness defects that require reconstruction. Although multiple alloplastic materials are available, they are a second choice, in the authors’ opinion, due to their cost of fabrication and increased risk of complete loss as a result of infection.

Special consideration must be given to the pediatric patient who has a congenital or an acquired full-thickness cranial defect. The calvaria has potent regenerative abilities in the pediatric patient (those under 2 years of age), mainly owing to the osteogenic properties of the dura and to a lesser extent the pericranium. However, as the patient ages, the “critical defect” size is reduced, and the cranium is more prone to incomplete regeneration after surgical insult.

Depending on the age of the patient and the size of the defect, reconstruction can be completed with resorbable mesh and cortical shavings, in situ split-thickness harvest and transposition, and full-thickness harvest with splitting and reconstruction of both the donor site and affected area.

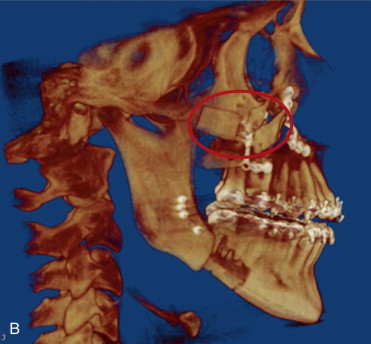

Stabilizing Craniomaxillofacial Osteotomies

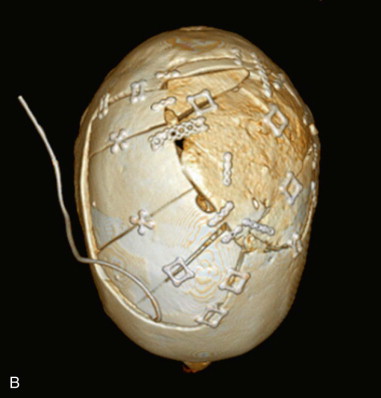

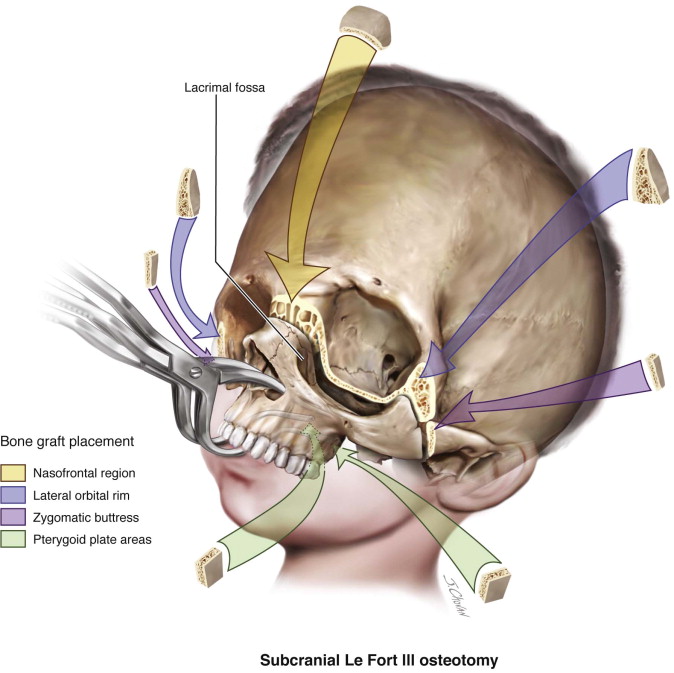

Wassmund, Axhausen, Schuchardt, Gillies, Trauner, Schmid, and others all have reported cases of mobilization and advancement of the mandible and midface for pathologic, congenital, and post-traumatic deformities. However, Obwegeser and Tessier refined and popularized many of the craniomaxillofacial procedures that are used contemporarily. Stabilization of osteotomy sites with bone grafts is a common theme and is recommended for significant advancements to aid in both healing and minimization of postoperative relapse ( Figure 125-2 ). Grafts are commonly placed in an interpositional fashion at the zygomaticofrontal, nasofrontal, pterygomaxillary, and nasomaxillary buttresses. Their use is also advised for significant advancement of the mandible with inverted L procedures and sliding step genioplasties.

Onlay Bone Augmentation

Conventional orthognathic surgical procedures (i.e., bilateral sagittal split osteotomy [BSSO] and Le Fort I osteotomy) are primarily used to correct dentofacial relationships. However, patients with abnormal facial proportions often benefit from further hard tissue augmentation in addition to corrective surgery. Split-thickness calvarial onlay bone grafts can significantly improve the esthetic outcome when appropriately applied ( Figure 125-3 ).

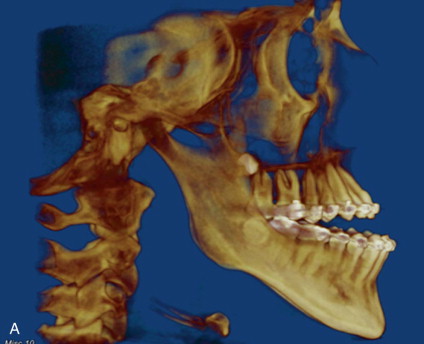

Cleft Bone Grafting

Patients born with a cleft lip and/or cleft palate often have bony clefts involving the maxilla, alveolar ridge, and nasal floor. Although the anterior iliac crest is the gold standard for secondary bone grafting, the calvaria is a convenient and effective source of bone for narrow cleft reconstruction ( Figure 125-4 ) or for reaugmentation for prosthetic or orthodontic indications. Patients with a cleft also commonly undergo orthognathic surgery secondary to midface deficiency and may benefit from grafting for osteotomy stabilization in addition to onlay augmentation.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses