History of the Procedure

Extensive details of the history of cosmetic blepharoplasty are provided by Gabriela Espinoza and John Holds in their excellent 2005 paper on the evolution of eyelid surgery. In the first century ad , Aulus Cornelius Celsus described the excision of upper eyelid skin for the treatment of “relaxed eyelid.” One thousand years ago, in Baghdad, Ali ibn Isa described a technique, recorded in the Greek writings of Claudius Galen ( ad 130-200) for removing excess upper lid skin by compressing the tissue to cause necrosis. Reports from surgeons in Europe in the early nineteenth century revealed substantial interest in upper and lower eyelid surgery. The techniques saw continued improvement throughout the twentieth century as surgeons acquired a better understanding of the relevant anatomy, and efforts to reduce complications progressed. The first significant contribution from the United States came in 1907, from Conrad Miller, in his book, Cosmetic Surgery: The Correction of Featural Imperfections . In 1951, Salvador Castañares described the anatomic details of the orbital fat pockets, making the surgical approaches more precise and problem-oriented. Interest and technical improvements in cosmetic blepharoplasty continue to progress, making it one of the most sought-after and effective facial cosmetic procedures available.

History of the Procedure

Extensive details of the history of cosmetic blepharoplasty are provided by Gabriela Espinoza and John Holds in their excellent 2005 paper on the evolution of eyelid surgery. In the first century ad , Aulus Cornelius Celsus described the excision of upper eyelid skin for the treatment of “relaxed eyelid.” One thousand years ago, in Baghdad, Ali ibn Isa described a technique, recorded in the Greek writings of Claudius Galen ( ad 130-200) for removing excess upper lid skin by compressing the tissue to cause necrosis. Reports from surgeons in Europe in the early nineteenth century revealed substantial interest in upper and lower eyelid surgery. The techniques saw continued improvement throughout the twentieth century as surgeons acquired a better understanding of the relevant anatomy, and efforts to reduce complications progressed. The first significant contribution from the United States came in 1907, from Conrad Miller, in his book, Cosmetic Surgery: The Correction of Featural Imperfections . In 1951, Salvador Castañares described the anatomic details of the orbital fat pockets, making the surgical approaches more precise and problem-oriented. Interest and technical improvements in cosmetic blepharoplasty continue to progress, making it one of the most sought-after and effective facial cosmetic procedures available.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

The term blepharoplasty covers a wide range of eyelid surgical procedures. This chapter focuses on the basic cosmetic blepharoplasty surgical procedures.

The eyes are probably the most important facial anatomic structures when it comes to communication of emotion, age, health, and attitude. In very subtle ways, they convey love, hate, fear, enthusiasm, sadness, happiness, and innumerable other emotions. They frequently tend to show signs of aging and ill health before these states are noticeable anywhere else. During conversation, we tend to focus on the other person’s eyes as a way to assess their emotional response to what we are saying. We tend to scrutinize the eyes of others, consciously or subconsciously, to learn more about them. We may see eyes that make the person look older than their stated age or less healthy than they claim. When we look in the mirror, we may be dismayed to come to similar conclusions about ourselves. The recognition that our eyes are not conveying the best message to others is the key stimulus for seeking a blepharoplasty.

The term blepharoplasty , as typically used today, describes cosmetic surgical procedures that improve the appearance of the upper or lower eyelids. The indications for upper lid blepharoplasty include dermatochalasis, asymmetry, fat herniation, muscle laxity, and an excessively high, low, asymmetric, or poorly defined lid crease.

The typical indications for lower lid blepharoplasty include dermatochalasis and herniated fat. Relatively uncommon indications include ectropion, entropion, and horizontal lid laxity or scarring causing an abnormal contour of the lid margin. The cosmetic surgeon should be able to recognize and evaluate these conditions, in addition to upper lid ptosis, brow ptosis, lateral canthal dystopia, and numerous other cosmetic eyelid problems that contribute to unesthetic lids. However, treatment for most of these other conditions is beyond the scope of this chapter.

The unesthetic eyelid conditions that prompt people to seek cosmetic blepharoplasty are almost always due to changes related to aging, genetic factors, or environmental factors, such as sun damage and smoking. Occasionally, blepharoplasty is indicated to treat complications of previous blepharoplasties or the results of traumatic injuries. Certainly, patients seeking blepharoplasty are almost always trying to achieve a more youthful and attractive appearance ( Figure 136-1 ).

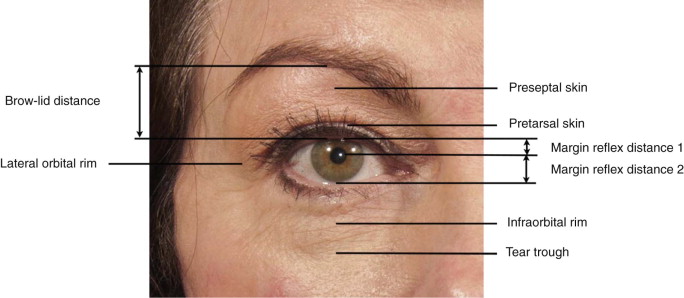

The preoperative assessment for blepharoplasty depends on a thorough appreciation of the normal anatomy and the degenerative changes associated with aging. The factors that contribute to unesthetic contours must be studied and applied to the evaluation. These factors include the bony anatomy and the anatomy of the periorbital soft tissues, in addition to the lids. Analysis of the eyelid contours can be facilitated by measuring the relationship between several anatomic structures. These measurements include the brow-lid margin distance, the palpebral fissure width, the margin reflex distance-1 (MRD 1 ), and the margin reflex distance-2 (MRD 2 ). The surgeon should also evaluate for dermatochalasis, prolapse of the lacrimal gland, horizontal lid laxity, fat herniation, orbicularis muscle hypertrophy, adequacy of inferior orbital rim and cheek projection and support, lower lid retraction, and structural asymmetry. All of the information gathered is used to formulate a treatment plan. The treatment plan should focus on the patient’s complaints and goals.

Limitations and Contraindications

There are limitations to what can be achieved with any blepharoplasty. Some conditions that may appear to be improvable with upper lid blepharoplasty may be only slightly improved, or even made worse, by the procedure. The most common limitation, from an esthetic standpoint, is brow ptosis, which may be present but not readily evident due to compensatory frontalis muscle hyperactivity. The surgeon should be careful to ensure that the frontalis muscles are relaxed when evaluating brow-lid esthetics. When very low brows are present, with a substantially reduced brow-lid margin distance, upper lid blepharoplasty with skin excision frequently results in additional lowering of the brows, minimal to no improvement in upper lid exposure, and an unimproved or worsened appearance. Excess skin on the upper lid may be partially or entirely due to the brow ptosis. If it is entirely due to the brow ptosis, an excellent result will be obtained with a browlift alone. If residual excess upper lid skin is present when the brow is raised to the ideal position, excision of some upper lid skin may be necessary, in addition to the brow lift, to obtain the best result.

Cosmetic limitations with lower lid blepharoplasty are primarily related to excessive horizontal lid laxity. The amount of skin that can be excised under this condition is limited by the degree of laxity. If too much skin is excised, lower lid ptosis or ectropion may develop. Additional surgery, such as lateral canthopexy, canthoplasty, or lateral retinacular suspension, may be necessary to achieve an optimal cosmetic result. Proptosis due to skeletal dysmorphia or thyroid dysfunction may dramatically limit or prevent the removal of any skin for fear of increasing the apparent proptosis by lowering the level of the lid margin. Horizontal lid tightening is frequently contraindicated in these situations.

Other relative contraindications include a history of keloid formation, contralateral blindness, a bleeding disorder, and medical problems such as poorly controlled hypertension or poorly controlled diabetes. As with other cosmetic surgical procedures, patients who want blepharoplasty in the expectation of secondary gains, such as improved interpersonal relationships or social status, may not be good candidates for this procedure.

Technique: Upper Lid Blepharoplasty

Step 1:

Skin Marking

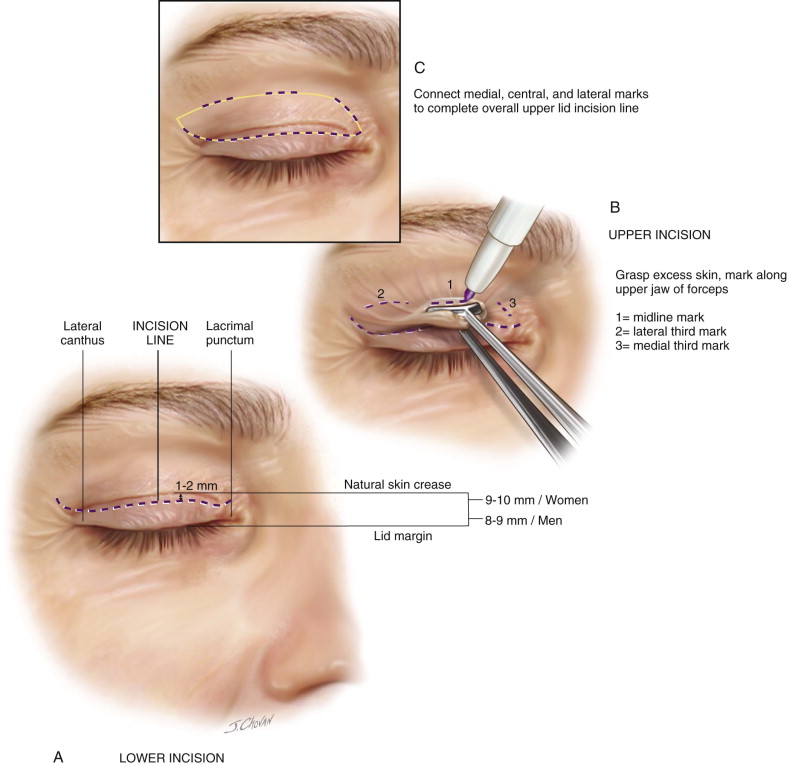

Marking the upper lid incisions with the patient in a supine position has the advantage of letting the brow migrate superiorly to a relaxed position. This is the position the patient will be in when sleeping, so marking in this position helps to maintain sufficient skin to prevent lagophthalmos and associated conjunctival exposure during sleep. The skin may also be marked with the patient in the upright position by holding the brow at the ideal or normal relaxed position during the marking ( Figure 136-2, A – C ).

Identify the natural lid crease about 9 to 10 mm above the lid margin in women and 8 to 9 mm in men. Use a skin marking pen to mark the planned lower incision line about 1 to 2 mm below this crease. The medial extent of the line should be limited to the lacrimal punctum. If skin lateral to the lateral canthus must be excised, curve this lower incision line superiorly along natural skin tension lines as it extends lateral to the canthus. Minimize this lateral extension, if possible, because the skin tends to scar more noticeably in this area. However, insufficient lateral extension may leave unesthetic excess lateral skin. The lateral end of the lower incision can be brought down to within about 4 mm of the lateral canthus.

Grasp the skin in the midline of the upper lid with a Bishop-Harmon forceps and lift away from the globe. Place the lower jaw of a Green fixation forceps on the lower incision line and grasp as much of the lifted skin as possible without everting the lashes or creating lagophthalmos. Mark the skin along the upper jaw of the forceps. Repeat this at the lateral and medial thirds without creating lagophthalmos. Draw a smoothly curved line across the lid through these marks. If necessary, extend the line 5 to 10 mm lateral to the lateral canthus to meet the end of the lower line. This line is the path of the upper incision.

Preoperative recognition of brow ptosis and globe prominence should be taken into account when marking the skin so that too much skin is not excised. There should be at least 22 mm of skin remaining between the lower margin of the brow and the upper lid margin in the midline to prevent lagophthalmos ( Figure 136-2, D – F ).

Step 2:

Injection of the Local Anesthetic

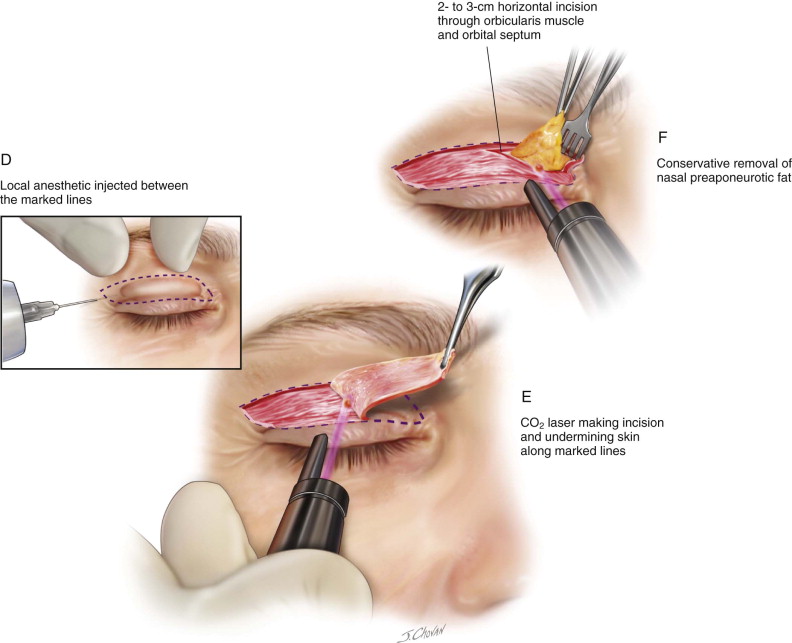

Apply ophthalmic lubricant to the eyes. Place lubricated metal eye shields if using a laser. Inject 1.5 cc Marcaine 0.5% with epinephrine 1 : 100,000 subcutaneously into each upper lid between the marked lines. Apply mild pressure to prevent bruising while waiting for vasoconstriction.

Step 3:

Incisions and Undermining of the Skin

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses