Introduction

Evidence comparing periodontal conditions in orthodontic patients who regularly use or do not use dental floss is scarce.

Methods

The subjects were 330 patients who had been under fixed orthodontic treatment for at least 6 months. They were examined by 1 calibrated examiner for plaque and gingival indexes, probing pocket depths, clinical attachment losses, and excessive resin around brackets. Socioeconomic background, time with orthodontic appliances, and use of dental floss were assessed in interviews. Unadjusted and multiple logistic regression analyses were used to assess the associations.

Results

The results demonstrated statistically significant higher means of plaque index, gingival index, pocket probing depth, and clinical attachment loss for nonusers of dental floss. Intragroup analyses showed higher means of these parameters in proximal sites and posterior teeth, compared with their counterparts’ buccal and lingual sites and anterior teeth, respectively. After multivariate analysis, male subjects ( P = 0.044) with a household income less than 5 national minimum wages ( P = 0.044), and nonusers of dental floss ( P = 0.000) showed higher probabilities of gingival bleeding (>30%) than did their counterparts.

Conclusions

Orthodontic patients who use dental floss regularly have somewhat better gingival conditions than those who do not use floss.

Clinical studies have indicated that orthodontic treatment can be associated with decreased periodontal health. However, the majority of the studies concluded that overall gingival alterations are transient, with little or no permanent damage to the periodontal supporting tissues. Clinical alterations during orthodontic treatment include gingival enlargement, covering significant portions of the teeth; this might further compromise plaque control and esthetics. Part of the explanation for this is the microbial shift, both quantitative and qualitative, after placement of fixed orthodontic appliances.

Proximal tooth surfaces consistently harbor greater amounts of plaque than nonproximal sites; this suggests that interdental cleaning is not adequate. The presence of orthodontic appliances contributes to dental plaque accumulation and retention, and also increases the skill and effort required to maintain good oral hygiene, especially on proximal surfaces. The use of dental floss for interproximal plaque control is difficult for most people because it requires time and dexterity; therefore, adequate removal of interproximal plaque is restricted to a small fraction of the population. This is no different for patients having fixed orthodontic therapy. Perhaps this is a reason that gingivitis and periodontitis are more prevalent and, frequently, more severe on proximal surfaces.

Toothbrushing alone does not adequately remove proximal plaque. Some clinical studies have shown that the correct use of dental floss leads to significant improvements in proximal gingival conditions. On the contrary, other studies did not obtain such results with the inclusion of flossing during a short supervised program of oral hygiene. This could indicate that, if brushing is performed adequately, some effect on proximal surfaces can be achieved. It is then possible that levels of plaque removal, obtained with only a conventional toothbrush, might be sufficient for the maintenance of proximal gingival health.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies comparing periodontal conditions in orthodontic patients who regularly use or do not use dental floss. In this study, we aimed to test the null hypothesis of no difference in the mean plaque and gingivitis values on the proximal surfaces in patients with fixed orthodontic appliances who are or are not regular dental floss users, against the working hypothesis that there would be less plaque and gingivitis on the proximal surfaces in dental floss users.

Material and methods

This cross-sectional survey examined subjects from 14 to 30 years of age who were under orthodontic treatment in an orthodontic graduate program in Santa Maria, Brazil. Ethical approval from the Franciscan University Center Ethical Committee was obtained before the study (protocol registration number 1246 of the National Ethics Committee). Subjects who agreed to participate signed an informed consent form. Patients diagnosed with oral pathologic conditions were advised to seek consultation and treatment.

To be eligible for the study, subjects were required to have been undergoing simultaneous full-arch maxillary and mandibular fixed orthodontic therapy for at least 6 months. Those with diseases and conditions that could pose health risks to the participant or interfere with the clinical examination, and those with physical or mental handicaps that would compromise manual dexterity, were not included.

The orthodontic dental clinic of the Advanced Postgraduate Unit of Ingá College, Santa Maria, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, was treating during the data collection period an estimated 700 patients. Of these, approximately 600 came for continuation of treatment and were assessed for eligibility criteria. This resulted in 400 eligible patients according to the eligibility criteria. Of these, 330 were evaluated, resulting in a nonresponse rate of less than 20%. In this investigation, the study sample comprised 330 patients aged 14 to 30 years, including 171 (51.8%) female and 159 (48.2%) male subjects; 263 (79.7%) were white, and 67 (20.3%) were of other ethnicities. The clinical examinations were performed between September 2009 and July 2010.

A calibrated examiner (F.B.Z.) performed all clinical examinations, with the aid of a dental assistant for recording. All permanent, fully erupted teeth, excluding the third molars, were examined by using a manual periodontal probe (Neumar, São Paulo, Brazil). Six sites (mesiobuccal, midbuccal, distobuccal, distolingual, midlingual, and mesiolingual) were assessed for each tooth.

The teeth in each quadrant were dried with a blast of air, and the plaque index and the gingival index were recorded. Probing pocket depth (distance from the free gingival margin to the bottom of the pocket or sulcus), clinical attachment loss (distance from the cementoenamel junction to the bottom of the pocket or sulcus), and bleeding on probing were also assessed. When the cementoenamel junction could not be located by the probe, it was assumed to be established at the bottom of the pocket. Measurements were made in millimeters and rounded to the lower whole millimeter.

The excess resin around the brackets was dichotomously assessed visually, by inspection with a probe around the bracket on the buccal surface of each bonded bracket. The buccal surface was divided into distal, mesial, and cervical aspects. Excess resin less than 1 mm from the gingival margin was considered to be positive.

After the clinical examination, all subjects were interviewed to gather demographic, socioeconomic, and oral health-related data by using a structured written questionnaire. The main clinical independent variable was the declared frequency of dental flossing, reported in the questionnaire. Regular interdental hygiene was defined as the regular use of dental floss, at least once a day. Nonusers of dental floss were defined as subjects who did not use interdental oral hygiene devices every day, or who did not perform interdental hygiene.

The examiner (F.B.Z.) was trained and calibrated in performing the clinical measurements before the examinations. For the assessment of measurement reproducibility, we used replicated periodontal measurements, performed with a 2-day interval. At the site level, reproducibility was assessed by weighted kappa (±1 mm) for probing pocket depth and clinical attachment loss, and the results were 0.73 and 0.68, respectively.

Statistical analysis

In this study, potential risk indicators were studied by comparing subjects with higher proximal bleeding and gingival conditions. The subjects were classified into 2 groups according to proximal bleeding (<30% and ≥30% of sites with marginal bleeding). Race was scored as white or other ethnicity. Socioeconomic status was scored by each subject’s education (≤11 years or >11 years). Information about family economy was scored (≤5 times the national minimum wage or >5 times the national minimum wage). The plaque index and the gingival index were dichotomized, respectively, as visible plaque (present or absent) and gingival bleeding (present or absent), with scores of 0 and 1 for each index considered “absent” and scores of 2 and 3 considered “present.” The percentages of sites per person with visible dental plaque, gingival bleeding, and bleeding on probing were calculated by dividing the number of sites for each variable by the total number of sites for each subject. The unit of analysis was the subject, the chosen level of statistical significance was 5%, and 95% CI values were calculated. Univariable analyses were used to compare the means of the plaque index, gingival index, pocket probing depth, clinical attachment loss, and percentage of sites with visible plaque and gingival bleeding in the dental floss and nondental floss users. Further comparisons were performed by using logistic regression analysis, adjusting for sex, age, family income, excess resin around brackets, and use of dental floss. Logistic regression analysis was used to model the relationship between persons with gingival bleeding more than 30% (generalized gingivitis) and various risk indicators. Preliminary analyses were performed by using univariable models. Next, a multivariable analysis was performed. Only exposures appearing in the univariable analyses associations with P ≤0.20 were included in the final model, with calculations of adjusted odds ratios for gingival bleeding more than 30% and 95% CI. Confounding and interaction effects were assessed. Goodness-of-fit of the final model was assessed by using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Data were statistically analyzed by using the statistics data editor (version 17.0; PASW, Chicago, Ill).

Results

All eligible subjects from the cross-sectional sample completed the questionnaires and clinical assessments. The subjects were predominantly white; almost 50% were older than 19 years. Most average incomes were less than 5 minimum monthly wages (approximately $290 each wage). A total of 159 (48.1%) had at least completed a high school education. A total of 145 (43.9%) of the subjects had been under orthodontic treatment for more than 1 year, and 81 (24.5%) subjects reported the use of dental floss every day. Most subjects (82.7%) had gingival bleeding at more than 30% of their proximal sites. All participants claimed to use a toothbrush regularly at least once a day. None used either toothpicks or interdental brushes.

Table I gives the means of the plaque index and the gingival index for the different sites, according to the subjects’ use of dental floss. Statistically significant differences in the means of the plaque and gingival indexes among both dental floss users and nonusers for the whole mouth, and the buccal and proximal surfaces, were observed. When the plaque and gingival indexes were analyzed separately for the anterior and posterior teeth, statistically significant higher means were found for the plaque index in nondental floss users. However, the gingival index presented statistically significant differences only for posterior teeth, with a higher gingival index mean in nondental floss users. Within-groups plaque index and gingival index showed higher means for proximal than buccal sites, and the posterior teeth showed higher plaque index and gingival index means, compared with the anterior teeth, for both dental floss users and nonusers ( Table II ).

| PlI | P ∗ | GI | P ∗ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole mouth | B/L | Pl | Whole mouth | B/L | Pl | |||

| NDFU | 1.17 (0.11) | 1.16 (0.19) | 1.18 (0.31) | <0.001 | 1.29 (0.19) | 0.89 (0.19) | 1.49 (0.10) | <0.001 |

| DFU | 0.95 (0.29) | 0.96 (0.24) | 0.97 (0.22) | 0.438 | 1.20 (0.20) | 0.82 (0.18) | 1.43 (0.60) | <0.001 |

| P † | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.14 | <0.001 | ||

∗ Intragroup comparisons (proximal sites vs buccal and lingual surfaces) with the Wilcoxon test.

† Intergroup comparisons (dental floss users vs nonusers) with the Mann-Whitney test.

| PlI (proximal sites) | P ∗ | GI (proximal sites) | P ∗ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior teeth | Posterior teeth | Anterior teeth | Posterior teeth | |||

| NDFU | 0.79 (0.18) | 1.44 (0.15) | 0.004 | 1.24 (0.13) | 1.69 (0.11) | 0.009 |

| DFU | 0.72 (0.21) | 1.15 (0.36) | <0.001 | 1.21 (0.50) | 1.58 (0.13) | <0.001 |

| P † | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.164 | <0.001 | ||

∗ Intragroup comparisons (anterior teeth vs buccal and posterior teeth) with the Wilcoxon test.

† Intergroup comparisons (dental floss users vs nonusers) with the Mann-Whitney test.

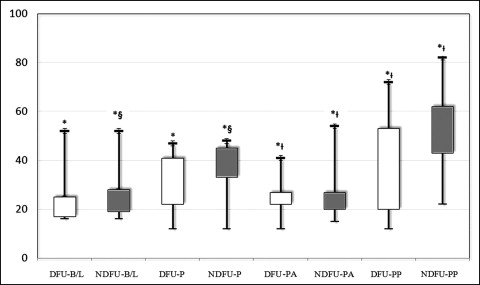

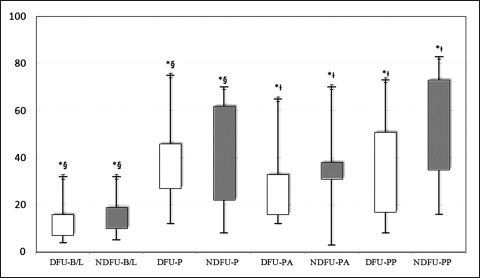

Figures 1 and 2 present the dichotomous versions of the plaque and gingival indexes, called visible plaque and gingival bleeding, respectively. In all analyzed sites, higher percentages of visible plaque and gingival bleeding were observed for nonusers of dental floss. When within-group differences among dental floss users and nonusers were analyzed, statistically higher percentages of visible plaque and gingival bleeding in the posterior teeth compared with their anterior counterparts were observed. For nonusers of dental floss, statistically higher percentages of visible plaque and gingival bleeding in the palatal than in the buccal surfaces were found. However, for dental floss users, despite the higher percentages of visible plaque and gingival bleeding in the palatal surfaces compared with the buccal surfaces, a statistically significant difference was observed only for gingival bleeding.

Data related to probing pocket depth and clinical attachment levels are shown in Table III . Statistically higher means for pocket probing depth and clinical attachment loss were observed in dental floss nonusers. In the within-groups comparisons, proximal sites showed statistically higher means of pocket probing depth and clinical attachment loss than did the buccal and lingual surfaces.

| Probing depth | P ∗ | Clinical attachment loss | P ∗ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buccal and lingual surfaces | Proximal sites | Buccal and lingual surfaces | Proximal sites | |||

| NDFU | 1.31 (0.10) | 2.09 (0.15) | <0.001 | 1.57 (0.29) | 1.63 (0.10) | <0.001 |

| DFU | 1.30 (0.11) | 2.03 (0.21) | <0.001 | 1.47 (0.10) | 1.58 (0.11) | 0.002 |

| P † | 0.009 | 0.006 | <0.001 | 0.001 | ||

∗ Intragroup comparisons (proximal sites vs buccal and lingual surfaces) with the Wilcoxon test.

† Intergroup comparisons (dental floss users vs nonusers) with the Mann-Whitney test.

Table IV gives the means, medians, standard deviations, and percentiles of subjects with generalized gingivitis, according to independent variables. Statistically significant differences were observed between the sexes, with male subjects having higher percentages of gingival bleeding, and for different ages, with higher medians for subjects 14 to 19 years old. Patients from families with incomes more than 5 national minimum wages had statistically higher medians of gingival bleeding. Moreover, subjects with excess resin around the brackets and nonusers of dental floss exhibited statistically higher medians of gingival bleeding than did their counterparts.

| Variable | n (%) | With proximal gingival bleeding >30% | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (±SD) | Median (Q25-Q75) | |||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 153 (56.0) | 50.31 (±11.07) | 46.42 (46.42-61.75) | <0.001 ∗ |

| Female | 120 (44.0) | 40.82 (±10.56) | 42.24 (38.85-56.30) | |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White | 222 (81.3) | 49.73 (±10.63) | 48.24 (43.71-50.89) | 0.276 ∗ |

| Other | 51 (18.7) | 51.69 (±11.67) | 50.89 (42.85-65.20) | |

| Age (y) | ||||

| 14-19 | 140 (51.3) | 51.62 (±11.80) | 50.89 (42.85-62.50) | 0.024 † |

| 20-24 | 96 (35.2) | 45.48 (±5.22) | 46.42 (45.21-46.84) | |

| 25-30 | 37 (13.6) | 50.50 (±10.99) | 46.24 (43.44-55.94) | |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Household income (wages) | ||||

| ≤5 | 230 (84.2) | 51.25 (±11.23) | 50.89 (46.42-62.50) | <0.001 ∗ |

| >5 | 43 (15.8) | 43.91 (±5.15) | 46.42 (42.85-48.24) | |

| Subject’s schooling (y) | ||||

| ≤11 | 144 (65.2) | 50.82 (±11.36) | 47.28 (44.31-63.50) | 0.129 ∗ |

| >11 | 129 (34.8) | 48.73 (±9.68) | 46.22 (42.88-63.77) | |

| Clinical status | ||||

| Excessive resin | ||||

| <18% | 243 (85.2) | 44.86 (±4.55) | 45.24 (41.75-49.12) | 0.005 ∗ |

| >18% | 30 (11.0) | 50.74 (±11.21) | 46.62 (42.95-61.70) | |

| Dental floss users (%) | ||||

| Yes | 53 (19.4) | 44.33 (±6.75) | 45.23 (40.24-53.42) | <0.001 ∗ |

| No | 220 (80.6) | 51.48 (±11.18) | 50.89 (44.62-66.50) | |

| TUFO (mo) | ||||

| 6-12 | 155 (56.8) | 50.98 (±11.54) | 47.28 (45.86-58.42) | 0.121 ∗ |

| >12 | 118 (43.2) | 48.93 (±9.75) | 43.68 (42.56-50.89) | |

Table V reports univariate and multivariate models for gingival bleeding greater than 30%, related to independent variables. In the crude model, male subjects ( P = 0.000), subjects with a household income less than 5 national minimum wages ( P = 0.014), those with schooling less than 11 years ( P = 0.000), those with excess resin around the brackets of more than 18% ( P = 0.002) of the teeth, and nonusers of dental floss ( P = 0.000) had higher probabilities of gingival bleeding (>30%) than did their counterparts. After adjustment, male subjects ( P = 0.044), subjects with a household income less than 5 national minimum wages ( P = 0.044), those excess resin around the brackets ( P = 0.037), and nonusers of dental floss ( P = 0.000) showed higher probabilities for the same outcome as their counterparts. However, schooling lost its significance after adjustment for the other variables that remained in the model.

| Variable | Total | n (%) without GG | n (%) with GG | Crude OR for PGB (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted ∗ OR for PGB (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Sex (n) | |||||||

| Male | 159 (51.8) | 39 (68.4) | 120 (44.0) | 2.76 (1.5-5.07) | 0.000 | 1.99 (1.11-3.92) | 0.044 |

| Female | 171 (48.2) | 18 (31.5) | 153 (56.0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Ethnicity (%) | |||||||

| White | 263 (79.7) | 41 (71.9) | 222 (81.3) | 1 | 0.109 | † | |

| Other | 67 (20.3) | 16 (28.1) | 51 (18.7) | 0.58 (0.30-1.13) | |||

| Age (y) | |||||||

| 14-19 | 162 (49.1) | 22 (38.5) | 140 (51.3) | 0.58 (0.25-1.33) | 0.222 | _ | |

| 20-24 | 121 (36.7) | 25 (43.8) | 96 (35.2) | 0.60 (0.32-1.13) | |||

| 24-30 | 47 (14.2) | 10 (17.5) | 37 (13.6) | 1 | |||

| Socioeconomic status | |||||||

| Household income (Wages) | |||||||

| ≤5 | 270 (81.8) | 40 (70.1) | 230 (84.2) | 2.27 (1.18-4.37) | 0.014 | 1.88 (1.23-3.76) | 0.044 |

| >5 | 60 (18.1) | 17 (29.9) | 43 (15.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Subject’s schooling (y) (years) | |||||||

| ≤11 years | 171 (60.3) | 27 (47.3) | 144 (52.7) | 3.21 (1.77-5.81) | 0.000 | † | |

| >11 years | 159 (39.7) | 30 (52.7) | 129 (47.3) | 1 | |||

| Clinical status | |||||||

| Excessive resin (%) | |||||||

| <18 | 285 (86.4) | 42 (43.7) | 243 (85.2) | 1 | 0.002 | 1 | 0.037 |

| >18 | 45 (13.6) | 15 (26.3) | 30 (11.0) | 2.89 (1.43-5.43) | 4.34 (1.25-22.01) | ||

| Dental floss use | |||||||

| Yes | 81 (24.5) | 28 (49.0) | 53 (19.4) | 1 | 0.000 | 1 | <0.001 |

| No | 249 (75.5) | 29 (51.0) | 220 (80.6) | 4.00 (2.20-7.30) | 4.33 (1.94-9.65) | ||

| TUFO (mo) | |||||||

| 6-12 | 185 (56.1) | 30 (52.7) | 155 (56.8) | 1 | 0.566 | _ | |

| >12 | 145 (46.9) | 27 (47.3) | 118 (43.2) | 0.84 (0.47-1111.1.49) | |||

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses