Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

Thomas Anandale is the first surgeon credited with the description of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) surgery in his 1887 article in Lancet . However, Humphrey described access to the TMJ in 1856 for condylectomy and Riedel for meniscectomy in 1883. Anandale’s approach to the TMJ was very different than approaches utilized by today’s surgeons. He used a curved three-quarter-inch incision directly over the lateral ligament of the joint. This was then carried down to the capsule to access the joint.

In 1897, Stimson’s Manual of Operative Surgery described the excision of the mandibular condyle through a T -shaped incision with the horizontal arm lying over the inferior aspect of the zygoma and a vertical arm extending inferiorly through skin. In 1914, Murphy described the surgical correction of ankylosis with arthroplasty utilizing an L -shaped incision with the base along the superior aspect of the zygoma and the vertical arm extending from the most posterior position. He went on to describe the use of temporal fat and temporalis fascia as an interpositional flap. In 1939, Professor Wakely of King’s College published his arthroplasty technique utilizing a pedicled temporalis flap tunneled under the zygoma.

By the mid–twentieth century, most surgeons were trained in a standard preauricular approach with an anterior hockey stick at the superior margin. This incision is often modified so that it extends posterior to the tragus in an endaural approach. The approach was further modified with a postauricular approach, which reflects the ear anteriorly, allowing access to the TMJ with a well-hidden incision. Other approaches to the TMJ have been described and include rhytidectomal, intraoral, and submandibular methods.

History of the Procedure

Thomas Anandale is the first surgeon credited with the description of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) surgery in his 1887 article in Lancet . However, Humphrey described access to the TMJ in 1856 for condylectomy and Riedel for meniscectomy in 1883. Anandale’s approach to the TMJ was very different than approaches utilized by today’s surgeons. He used a curved three-quarter-inch incision directly over the lateral ligament of the joint. This was then carried down to the capsule to access the joint.

In 1897, Stimson’s Manual of Operative Surgery described the excision of the mandibular condyle through a T -shaped incision with the horizontal arm lying over the inferior aspect of the zygoma and a vertical arm extending inferiorly through skin. In 1914, Murphy described the surgical correction of ankylosis with arthroplasty utilizing an L -shaped incision with the base along the superior aspect of the zygoma and the vertical arm extending from the most posterior position. He went on to describe the use of temporal fat and temporalis fascia as an interpositional flap. In 1939, Professor Wakely of King’s College published his arthroplasty technique utilizing a pedicled temporalis flap tunneled under the zygoma.

By the mid–twentieth century, most surgeons were trained in a standard preauricular approach with an anterior hockey stick at the superior margin. This incision is often modified so that it extends posterior to the tragus in an endaural approach. The approach was further modified with a postauricular approach, which reflects the ear anteriorly, allowing access to the TMJ with a well-hidden incision. Other approaches to the TMJ have been described and include rhytidectomal, intraoral, and submandibular methods.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

Surgery is indicated to restore damaged or diseased tissue and remove tissue that cannot be salvaged. It is also used to promote healing of tissues by replacing missing tissue with grafts. An understanding of joint pathology and the role surgery plays in various pathologic entities is required. In 1994, Dolwick and Dimitrioulis described absolute and relative indications for arthrotomy. Absolute indications include ankylosis, both fibrous and osseous, neoplasia, recurrent or chronic dislocation, and developmental disorders including condylar hyperplasia. The relative indications include internal derangement, osteoarthrosis, and trauma.

Dolwick further divided TMJ surgery indications into general and specific. Surgery is indicated in patients who are unresponsive to nonsurgical therapy. This is with the caveat that they are following treatment regimens and that their problems are truly joint-related and not a myofascial pain disorder. Upon physical examination, pain will be localized to the TMJ, especially on functional loading and movement. Mechanical interference may also be appreciated. More specific indications include disorders not responding to TMJ arthrocentesis, chronic severe limited mouth opening, degenerative joint disease with intolerable pain and dysfunction, and severe joint disease identified on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The more localized the pain is to the TMJ, the better the surgical prognosis.

Eminectomy is indicated for recurrent mandibular dislocation. Recurrent dislocation is uncommon. A study conducted by Boering found an incidence of 1.8% in a population of 400 symptomatic TMJ patients. Often recurrent dislocations are found in people with joint laxity, those with internal derangement of the TMJ, and those with neurologic disorders who experience seizure or extrapyramidal symptoms from neuroleptic therapy. Recurrent dislocation causes injury to the disk, capsule, and ligaments, leading to internal derangement.

Limitations and Contraindications

Patient selection is of vital importance, and the practitioner must be clear in both the description of the diagnosis and the procedure. It is paramount to select patients who are compliant with treatment regimens, have a good understanding of their disorder, and do not have unrealistic expectations.

Technique: Arthroplasty

Step 1:

Prepping and Draping the Patient

Open TMJ surgery is performed under general anesthesia. The patient is placed supine on the operating table with the head turned to expose the side to be operated. Postsurgical infections are rare following TMJ surgery, and it is usually unnecessary to clip hair in the surgical field unless it will enter the wound during surgery. Prior to prepping the skin, an antibiotic ointment–impregnated (Cortisporin otic solution, Floxin, etc.) cotton pellet, petroleum gauze, or an impregnated Merocel ear packing (i.e., “pope” size Merocel) is placed into the external auditory canal. This minimizes entry of fluid into the ear during surgery, which could lead to postoperative irritation and pain of the canal or tympanic membrane. The skin is then prepped and draped to include the external ear, in case of need for cartilage harvest, preauricular skin including the zygomatic arch to the lateral canthus, and inferiorly to the mandibular border. A sterile adhesive border is then applied with the ear exposed and sterile drapes are placed.

Step 2:

Incision

The endaural approach will be described herein and is a modification of the preauricular approach. This approach places the incision on the tragus versus in the pretragal crease. If further access is required, an extension of the incision, as described by Al-Kayat and Bramley, into the temporal area about 1 cm above the superior margin of the palpable zygomatic arch is available. Prior to incision, local anesthetic is placed into skin marked for incision, but care is taken not to inject into deep tissues to avoid blocking the facial nerve. Some surgeons desire the use of a nerve stimulator. In that case, care must be taken to avoid the facial nerve, and anesthesia must be prohibited from utilizing neuromuscular blockade.

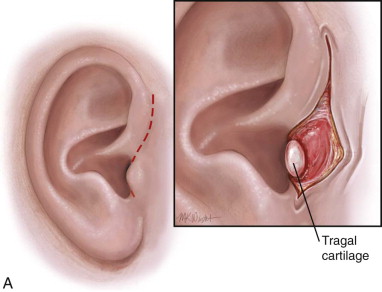

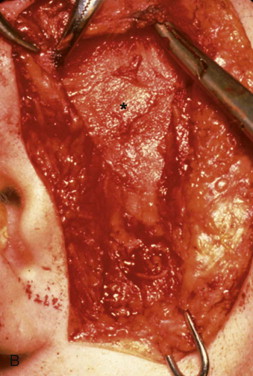

An incision is made from the uppermost point of the auricle inferior to the attachment of the ear lobule, with the middle portion of the incision hidden in the posterior tragus. Care is taken to avoid tragal cartilage with the possible complication of perichondritis, although some surgeons transect through the tragal cartilage. The incision is through the skin and subcutaneous tissue down to superficial temporalis fascia. A blunt instrument is then used to open a pocket anterior to the external auditory canal. The superficial temporal artery and vein are located deep to the subcutaneous tissue and may be encountered and ligated or retracted forward. Dissection is bluntly continued toward the superficial temporal fascia until the smooth, white, well-defined surface of the superficial surface of the temporalis fascia is encountered. When a small pocket has been developed, a Senn retractor is placed into the wound down to this layer. Another Senn is placed in the pretragal incision. The soft tissue in the depth of the wound has clearly defined landmarks that can then be sharply released using scissors ( Figure 129-1, A and B ).

Step 3:

Dissection to the Temporomandibular Joint Capsule

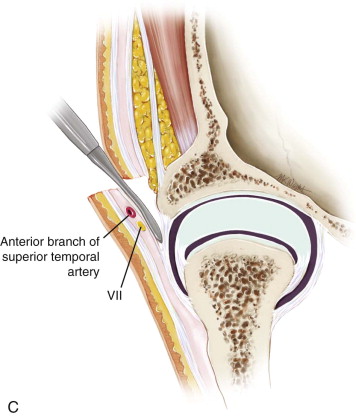

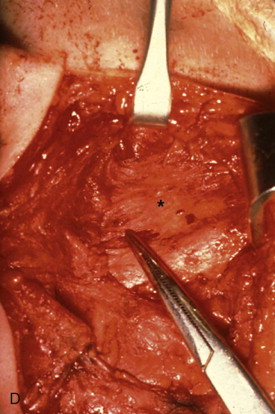

The superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia is now visible the entire length of the wound. A scalpel is used to incise this layer just anterior to the plane of dissection and parallel to the skin incision. A Molt periosteal elevator is then utilized to dissect over the periosteum anteriorly. Dissecting in this layer protects and allows retraction of branches of the facial nerve. This plane is superior to the lateral capsule of the TMJ and the posterior attachment of the parotideomasseteric fascia. This attachment is cut just anterior to the auditory canal and the fascia retracted anteriorly to expose the lateral capsule to view. Kitner retractors are very useful and cause minimal soft tissue injury during this process, and if performed in the correct layer, bleeding is minimized ( Figure 129-1, C and D ).

Step 4:

Exposing the Intra-articular Spaces

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses