Surgery to correct disorders of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) has been performed and documented since the mid-nineteenth century. Although earlier mentions may be found, Annandale’s brief 1888 Lancet article reports a remarkably modern surgical approach to the TMJ and procedure for disc repositioning and is often cited as the first description of TMJ disc surgery. In the decades to follow, pioneering surgeons published a variety of approaches to the TMJ, traversing the preauricular area vertically, horizontally, and by various L-shaped incisions. By the mid-twentieth century, most surgeons were trained in a standard vertical preauricular approach with an anteriorly directed hockey-stick curve at the superior margin. This skin incision is often modified by extending it posteriorly so that much of its length is hidden behind the tragus (endaural approach). A less commonly used approach is to make the incision behind the ear and, reflecting the ear anteriorly and sharply transecting the external auditory canal, access the TMJ from a well-hidden postauricular approach. This article does not describe indications for open TMJ surgery and discectomy or the relative role of this treatment among others, but focuses on the surgical technique used. Once the lateral capsule is reached, any of the open joint procedures described in this text may proceed, but this article describes a conservative discectomy without disc reconstruction. The following description uses a standard preauricular incision and dissection as performed by the author based on the collective experience and wisdom of many surgeons before him.

Patient preparation

Although case reports document open TMJ surgery under local anesthesia, most of these operations are performed under general anesthesia with the patient supine and head turned to expose the side to be operated. Worldwide, increased attention has recently been given to protocols enhancing patient safety, including checks to minimize the risk of wrong-side surgery. Because TMJ disease rarely shows obvious localizing external signs, the prudent surgeon makes full use of such routines to ensure that the correct joint is prepared for surgery. Postsurgical infections are exceedingly rare following TMJ surgery, and it is usually not necessary to clip hair in the surgical field unless it will be bothersome or enter the wound during surgery. Surgical antibiotic prophylaxis is generally used according to local guidelines and the surgeon’s discretion. Before prepping skin, an antibiotic ointment–impregnated cotton or gauze plug is gently inserted into the external auditory canal to minimize fluid entry during surgery, which could otherwise lead to postoperative irritation and pain of the canal or tympanic membrane. Contemporary surgical literature supports the use of chlorhexidine solutions to prep skin for incisions, but, because of its risk of eye injury, we use Betadine to prepare the external ear and preauricular area superiorly to several centimeters above the zygomatic arch, anteriorly to the lateral canthus of the eye, and inferiorly to the mandibular border. A smaller area is then surrounded with sterile drapes, leaving the ear exposed. A sterile adhesive barrier may be applied as well. However, like many widely practiced routines intended to prevent infection, this measure has little or no scientific evidence supporting routine use for TMJ procedures. Additional measures routinely endorsed for other orthopedic procedures, such as laminar flow operating rooms or spacesuits for operating room personnel, do not seem to further reduce the already-low infection rate for head and neck surgery.

Surgical anatomy

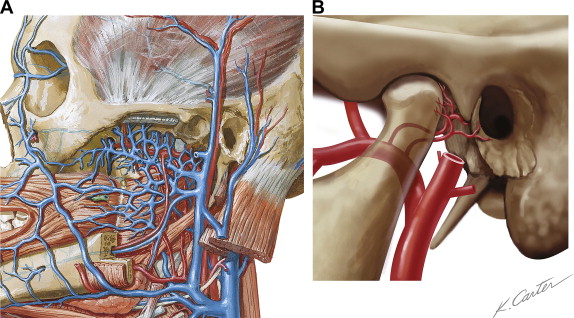

The preauricular approach to the TMJ passes through an area bounded posteriorly by the external ear and anterior wall of the external auditory canal, inferiorly by the main trunk of the facial nerve and the parotid gland, and anteriorly by the path of the temporal (frontal) branch of the facial nerve. The superior boundary of the space is more variable, and it is this direction in which dissection may be extended when additional access is needed. Within this space, the auriculotemporal nerve and superficial temporal artery and vein run inferiorly to superiorly, anterior to the ear and within the subcutaneous loose connective tissue superficial to the superficial temporal fascia ( Fig. 1 ). These vessels may usually be retracted anteriorly as dissection proceeds, although they often possess small posterior tributaries or branches that must be cauterized or ligated and divided.

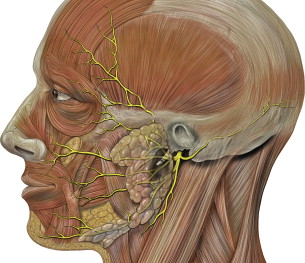

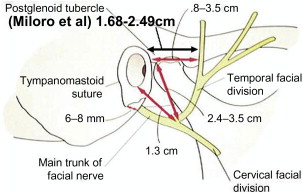

The course of the facial nerve and its branches ( Fig. 2 ) must be known to avoid violating the boundaries of safe surgery and creating a potentially paralyzing injury. In their landmark 1979 article, Al-Kayat and Bramley measured the location of the facial nerve’s main trunk and found that it runs no nearer than 1.5 cm below the inferior margin of the bony external auditory meatus and that the most posterior temporal branch of the nerve crosses the zygomatic arch anterior to the bony external auditory meatus at a minimum distance of 0.8 cm and mean of 2.0 cm. Similar cadaver studies by Woltmann found a minimum distance of 0.7 cm and a mean of 1.5 cm, whereas an elegant high-resolution MRI study of live subjects by Miloro and others measured a minimum distance of 1.7 cm and mean of 2.1 cm ( Fig. 3 ). Agarwal and others made a significant addition to the knowledge of the facial nerve’s path in 3 dimensions by showing in an anatomic study that the temporal branch lies in the loose areolar connective tissue layer between the superficial and deep temporal fascia as it crosses the zygomatic arch; it enters the superficial temporal fascia from its undersurface in a consistent region 1.5 to 3.0 cm above the zygomatic arch and 0.9 to 1.4 cm posterior to the lateral orbital rim ( Fig. 4 ).

Surgical anatomy

The preauricular approach to the TMJ passes through an area bounded posteriorly by the external ear and anterior wall of the external auditory canal, inferiorly by the main trunk of the facial nerve and the parotid gland, and anteriorly by the path of the temporal (frontal) branch of the facial nerve. The superior boundary of the space is more variable, and it is this direction in which dissection may be extended when additional access is needed. Within this space, the auriculotemporal nerve and superficial temporal artery and vein run inferiorly to superiorly, anterior to the ear and within the subcutaneous loose connective tissue superficial to the superficial temporal fascia ( Fig. 1 ). These vessels may usually be retracted anteriorly as dissection proceeds, although they often possess small posterior tributaries or branches that must be cauterized or ligated and divided.

The course of the facial nerve and its branches ( Fig. 2 ) must be known to avoid violating the boundaries of safe surgery and creating a potentially paralyzing injury. In their landmark 1979 article, Al-Kayat and Bramley measured the location of the facial nerve’s main trunk and found that it runs no nearer than 1.5 cm below the inferior margin of the bony external auditory meatus and that the most posterior temporal branch of the nerve crosses the zygomatic arch anterior to the bony external auditory meatus at a minimum distance of 0.8 cm and mean of 2.0 cm. Similar cadaver studies by Woltmann found a minimum distance of 0.7 cm and a mean of 1.5 cm, whereas an elegant high-resolution MRI study of live subjects by Miloro and others measured a minimum distance of 1.7 cm and mean of 2.1 cm ( Fig. 3 ). Agarwal and others made a significant addition to the knowledge of the facial nerve’s path in 3 dimensions by showing in an anatomic study that the temporal branch lies in the loose areolar connective tissue layer between the superficial and deep temporal fascia as it crosses the zygomatic arch; it enters the superficial temporal fascia from its undersurface in a consistent region 1.5 to 3.0 cm above the zygomatic arch and 0.9 to 1.4 cm posterior to the lateral orbital rim ( Fig. 4 ).