“The only thing new in the world is the history that you do not know.”

An advertisement in Dental Cosmos in 1900 boldly announced: “For the fitting of teachers and specialists in orthodontia. Two short sessions are held each year, beginning November 1 and May 1. Postgraduates in dentistry and only those thoroughly ethical received. Class limited to fifteen members. For information, address Edward H. Angle, MD, DDS, 1107 N. Grand Avenue, St. Louis, Missouri [italics added].”

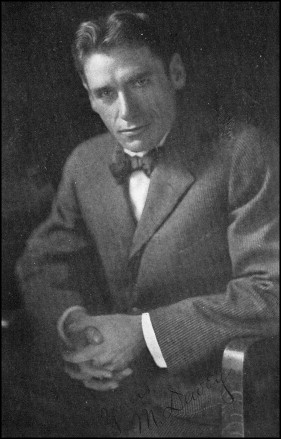

One year later, in St Louis, Angle led a group of dedicated specialists to form the Society of Orthodontists several doors away from the Missouri Medical College. Two years of intense planning and organization culminated in this meeting; as a result, the specialty of orthodontics was born. That same year, Dr Benno E. Lischer ( Fig 1 ), who eventually served as the Society’s president and dean of the Washington University School of Dentistry, dined with his friend and next-door neighbor at the Union Dairy Cafe on the corner of Washington and Jefferson Streets in St Louis. His chum was a young physician named Charles V. Mosby, whose practice was located in Lischer’s building. Their frequent topic of discussion was the possibility of establishing a journal dedicated solely to orthodontia. Mosby was then a general practice physician who was developing an enterprising interest in the publication of medico-dental specialty journals. Although the American Journal of Dental Science was established in 1840 in an effort to enhance dentistry’s professional image in an era of professional mistrust, orthodontics needed a journal that was committed to its specific interests. Fourteen years later, with Dr Martin Dewey ( Fig 2 ) as its first editor, the C. V. Mosby Company began publication of the International Journal of Orthodontia to meet that objective. This was the initial title of the publication we now call the American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics . Lischer subsequently remained intimately involved via his regular contributions in the International Portrait Series as one of the journal’s features. He continued to publish for years thereafter in a task he accepted graciously, since he believed that “orthodontic authors in those days were few in number.”

Ethics as applied to medico-dental practice and associated research is called bioethics. From the Journal ‘s inception, contributing authors have explored recurrent themes pertaining to bioethics. This early interest is a tribute to the keen foresight and enduring pride in professionalism that has persisted throughout the evolution of orthodontics. An early essay stressed that orthodontists’ first obligation is to benefit our patients, in a responsibility that supersedes those involved in an art business or trade. The patient’s interests remain premier. The commitment has subsequently been described as a covenant rather than a contractual agreement, signifying that the doctor-patient relationship surpasses that of solely payment for a specific service. This distinguishes the patient-doctor relationship from that of a trade.

Applicable ethical and bioethical topics have varied since the establishment of the Journal , but several have recurrently emerged. These have included issues related to transfer patients, unjustified criticism of colleagues, fee splitting, the need for ethical codes, professionalism, and more. The recurrence of these issues even a century after the Journal ‘s first publication is testimony of their pertinence.

Patient transfer

Transfer of orthodontic care from one practitioner to another has consistently elucidated an array of ethical topics. Ranging from discussions of patient autonomy (self-rule) to veracity (truth telling) and to justice (providing the patient with that which he deserves), the issue of patient transfer retains a contemporary application.

Although medico-dental treatment delivery followed a paternalistic approach until the late 20th century, a patient’s decision to transfer from one orthodontic provider to another evoked an early emphasis on patient autonomy. In a 1918 editorial printed in the International Journal of Orthodontia , Editor Martin Dewey identified 2 common reasons for elective patient transfer: personal incompatibility between the orthodontist and the patient, and the patient’s dissatisfaction with the treatment plan. As the Journal ‘s first editor, Dewey identified a common reason for dissatisfaction with the treatment plan as the patient’s preference for removable rather than fixed appliance therapy. This is a contemporary issue. It was not uncommon for orthodontists of the pre-Depression era to deny the patient’s right to transfer based on the initial orthodontist’s financial interests. The concern was that the initiating orthodontist might remain unremunerated for his expense and effort in delivering the fixed appliance.

Transfers involving patient relocation were also potentially problematic. Although it was then common courtesy for the second orthodontist to accept the fee schedule established by the initiating orthodontist, Dr Dewey objected to this practice. He recommended that the fees and choice of the appliance should be the prerogative of the second orthodontist. This opinion was later disputed by other authors who claimed that the second orthodontist should accept the fees of the initial orthodontist as an act of courtesy to both the patient and the initial provider.

In 1921, Young admonished clinicians to refrain from commenting on the extent or quality of a transfer patient’s treatment progress unless the original orthodontist accompanied the patient at the transfer visit. “The question … is [to identify] the proper policy to follow when a patient is under treatment by another orthodontist or dentist … desiring another opinion,” he wrote. “It is not advisable that the word of the patient, no matter how reliable he may be, should be taken against that of the practitioner, for it is not infrequent when misunderstandings arise between the patient and the professional man, that the patient gets the wrong impression or wrong point of view.” So true! He recommended that the second orthodontist should seek the initial orthodontist’s written approval before a transfer is consummated, again citing the initial orthodontist’s financial concerns as the motivation for this recommendation. He emphasized the responsibility of the initial orthodontist to locate a second orthodontist for the departing patient. Support of this opinion by luminaries such as Drs John V. Mershon, Oliver W. White, Charles A. Hawley, Guy G. Hume, and Lloyd S. Lurie was echoed.

The essay of Editor H. C. Pollock ( Fig 3 ) entitled “Orthodontic tolerance” is well-written support of the application of the Golden Rule in the transfer process. “One thing is certain,” Pollock wrote. “The orthodontist to whom the case is referred must lean backward and employ a wholesome creed of the Golden Rule, not only because it is the right thing to do, but also for the very practical reason that he himself may be the next to have his patient fall into another’s hands, where he will hope for tolerance with eyes uplifted … in the hope that his patient is in the hands of one with tolerance in his soul.” He wrote further that “intolerance by breaking public confidence can destroy the entire system upon which the specialty has been built.”

Pollock returned with another jewel 5 years later. Labeling transfers as the “orthodontist’s weakest link,” he viewed patient transfer as a potential vehicle for enhancing the specialty’s image. He envisioned the transfer process as a method of demonstrating the specialty’s communicability among its members. Likening patient transfer to that of a person giving directions to another with the intention of ensuring a safe arrival, the orthodontist should intend to facilitate the patient’s “safe arrival” (ie, the completion of treatment). Although treatment techniques differ among providers, he believed that a minimal change in the initial treatment course was best. He called for the specialty’s establishment of a conventional method of transfer.

The requirement of veracity (truth) in estimating remaining treatment time was a recurrent theme, as was the second orthodontist’s need to explain his reasons for replacing the initial fixed appliance with his own. The fee should be based on an “honest evaluation of the time spent and the appliance placed in relation to total fee quoted.” This applies to contemporary patient transfers as well. Total fee disclosure at the outset of treatment was then not universal but highly recommended. Unjustifiable criticism of the initiating orthodontist and commencement of treatment without production of adequate transfer records were discouraged.

Rathbone and Reynolds proposed an interesting classification system that included various types of transfer patients including student, permanent, and temporary transfers (eg, the summer tourist). Their recommendations pertaining to patient transfer were as follows.

The mobility of the American people for vocational and educational purposes has greatly increased the number of orthodontic transfer cases. … The management of transfer cases provides the greatest challenge to our professional behavior, and the public’s image of orthodontics rests upon our ability to meet this challenge. … Inherent in all transfer cases is the basic problem of who assumes responsibility; that the referring orthodontist is always correct in the eyes of the parents; that appliance design and treatment procedures will vary from operator to operator; that treatment will take longer and require more service; and that fee schedules are not uniform. … Transfer cases offer the orthodontist the greatest opportunity to prove the existence of professional ethics and to demonstrate professional courtesy. … In conclusion, there is no one answer to the many problems that confront the orthodontist in the management of transfer cases. … In the final analysis, the only real answer lies in the individual integrity of the orthodontists involved and the moral obligation which their consciences dictate.

Fee splitting

Contributors to the Journal have consistently viewed fee splitting, or commissions paid to a referral source, as unethical behavior. Early articles cited fee splitting as emanating from 2 origins. In 1923, Dr Dewey advised against referring patients to those commercial radiographic laboratories that paid the highest commissions to referring orthodontists. These were laboratories that produced diagnostic films as prescribed by orthodontists. He advised against the use of dental radiology laboratories in which the operators were not licensed physicians or dentists. He asserted that a professional referral—for either patient care or laboratory services—should depend on the person or entity that provides the service rather than a financial impetus. The “trouble lies with the dentist who accepts rebates,” he declared. In a strongly worded essay that denounced fee splitting, as well as dentists who accept commercial samples as incentives to prescribe products, Dr Clarence Simpson was emphatic. He stated: “The x-ray laboratories will continue to ‘graft’ from the ignorant public, so long as the ‘piker’ dentists support them to produce low-priced, high mortality dentistry, and a code of ethics will never make professional men of the dentists who collect and carry a bag of free samples at every convention.” In that same article, Dr J. E. Jelenik authored a colorful narrative, calling for a strict ethical code that “should straighten some crooks and toughen the paths of slippery boys who try to cheat without losing their society affiliations.” He called garish signage and advertising “self elevation … equaling greed and selfishness.” He continued: “Patients that come to you through any other manner than that of personal acquaintance or by recommendation of other patients of yours are seldom desirable.”

Dr Dewey warned that extending professional fee courtesies to dentists and physicians as a “bid for patronage” might infringe on the American Dental Association’s ethical code. In the orthodontist’s quest for new patients, Alstadt stated that “it is obvious that certain procedures such as kickbacks, tipping elevator girls, allowing unauthorized personnel to administer to patients and indiscriminate dental notices seeking patients are unethical.” Encouraging an ethical posture, he continued optimistically: “There have been but few instances where financial returns have not kept pace with ethical practices. … A gradual increase in clientele must follow, with augmented prestige in the community and in the profession” leading to respect and support within the community in which the professional practices. He advocated an ethical approach to marketing as the winning strategy for practice growth.

Fee splitting

Contributors to the Journal have consistently viewed fee splitting, or commissions paid to a referral source, as unethical behavior. Early articles cited fee splitting as emanating from 2 origins. In 1923, Dr Dewey advised against referring patients to those commercial radiographic laboratories that paid the highest commissions to referring orthodontists. These were laboratories that produced diagnostic films as prescribed by orthodontists. He advised against the use of dental radiology laboratories in which the operators were not licensed physicians or dentists. He asserted that a professional referral—for either patient care or laboratory services—should depend on the person or entity that provides the service rather than a financial impetus. The “trouble lies with the dentist who accepts rebates,” he declared. In a strongly worded essay that denounced fee splitting, as well as dentists who accept commercial samples as incentives to prescribe products, Dr Clarence Simpson was emphatic. He stated: “The x-ray laboratories will continue to ‘graft’ from the ignorant public, so long as the ‘piker’ dentists support them to produce low-priced, high mortality dentistry, and a code of ethics will never make professional men of the dentists who collect and carry a bag of free samples at every convention.” In that same article, Dr J. E. Jelenik authored a colorful narrative, calling for a strict ethical code that “should straighten some crooks and toughen the paths of slippery boys who try to cheat without losing their society affiliations.” He called garish signage and advertising “self elevation … equaling greed and selfishness.” He continued: “Patients that come to you through any other manner than that of personal acquaintance or by recommendation of other patients of yours are seldom desirable.”

Dr Dewey warned that extending professional fee courtesies to dentists and physicians as a “bid for patronage” might infringe on the American Dental Association’s ethical code. In the orthodontist’s quest for new patients, Alstadt stated that “it is obvious that certain procedures such as kickbacks, tipping elevator girls, allowing unauthorized personnel to administer to patients and indiscriminate dental notices seeking patients are unethical.” Encouraging an ethical posture, he continued optimistically: “There have been but few instances where financial returns have not kept pace with ethical practices. … A gradual increase in clientele must follow, with augmented prestige in the community and in the profession” leading to respect and support within the community in which the professional practices. He advocated an ethical approach to marketing as the winning strategy for practice growth.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses