7

Treatment of dental caries in the preschool child

S.A. Fayle

Chapter contents

7.2 Patterns of dental disease seen in preschool children

7.3 Identifying preschool children in need of dental care

7.4 Management of pain at first attendance

7.5 Principles of diagnosis and treatment planning for preschool children

7.7.1 Managing the preschool child’s behaviour in the dental setting

7.8 Treatment of dental caries

7.8.1 Temporization of open cavities

7.8.2 Definitive restoration of teeth

7.1 Introduction

Dental caries is still one of the most prevalent pathological conditions in the child population of most Western countries. A UK study of children aged from 1.5 to 4.5 years demonstrated that 17% have decay, and in many parts of the UK up to 50% of the child population has experience of decay by the time they are 5 years of age. Dental caries is associated with significant morbidity in children, and treatment of dental caries (and its sequelae) is currently the most common reason for a child’s requiring general anaesthesia (GA) in the UK. Successfully managing decay in very young children presents the dentist with a number of significant challenges. This chapter will outline approaches to the management of the preschool child with dental caries. (See Key Points 7.1.)

7.2 Patterns of dental disease seen in preschool children

7.2.1 Early childhood caries

Early childhood caries (ECC) is a term used to describe dental caries presenting in the primary dentition of young children. Terms such as ‘nursing bottle mouth’, ‘bottle mouth caries’, or ‘nursing caries’ are used to describe a particular pattern of dental caries in which the upper primary incisors and upper first primary molars are usually most severely affected. The lower first primary molars are also often carious, but the lower incisors are usually spared—being either entirely caries free or only mildly affected (Fig. 7.1). Some children present with extensive caries that does not follow the ‘nursing caries’ pattern. Such children often have multiple carious teeth and may be slightly older (3 or 4 years of age) at initial presentation (Fig. 7.2). This presentation is sometimes called ‘rampant caries’. However, there is no clear distinction between rampant caries and nursing caries, and the term ‘early childhood caries’ has been suggested as a suitable all-encompassing term.

In many cases, early childhood caries is related to the frequent consumption of a drink containing sugars from a bottle or ‘dinky’ type comforters (these have a small reservoir that can be filled with a drink) (Fig. 7.3). Fruit-based drinks are most commonly associated with nursing caries. Even many of those claiming to have ‘low sugar’ or ‘no added sugar’ appear to be capable of causing caries. The sparing of the lower incisors seen in nursing caries is thought to result from shielding of the lower incisors by the tongue during suckling, whilst at the same time they are being bathed in saliva from the sublingual and submandibular ducts. The upper incisors, on the other hand, are bathed in fluid from the bottle/feeder.

Figure 7.1 Early childhood caries presenting as nursing caries in a 2-year-old child.

Figure 7.2 Extensive caries affecting primary molars in a 4-year-old child.

Frequency of consumption is a key factor. Affected children often have a history of taking a bottle to bed as a comforter, or using a bottle as a constant comforter during the daytime. Research has shown that children who tend to fall asleep with the bottle in their mouths are most likely to get ECC, and this is probably a reflection of the dramatic reduction in salivary flow that occurs as a child falls asleep. However, the link between bottle habits and ECC is not absolute, and studies have suggested that other factors, such as linear enamel defects, malnutrition, and hypomaturation enamel defects on second primary molars, may play an important role in the aetiology of this condition in some children.

There is some circumstantial evidence that, in a few cases, ECC may be associated with prolonged on-demand breastfeeding. Breast milk contains 7% lactose and, again, frequent prolonged on-demand consumption appears to be an important aetiological factor. Most affected children sleep with their parents, suckle during the night, and are often still being breastfed at 2 years of age or older. It is important to appreciate that this does not imply that normal breastfeeding up to around 1 year of age is bad for teeth, but that prolonging on-demand feeding beyond that age may carry a risk of causing dental caries. Experiments in animal models suggest that cows’ milk (which contains 4% lactose) is not cariogenic, although some clinical studies have suggested that the night-time consumption of cows’ milk from a bottle might be associated with early childhood caries in some children. Whether or not cows’ milk has the potential to contribute to caries is currently uncertain. (See Key Points 7.2.)

Figure 7.3 Dinky type comforter with a small reservoir that can be filled with something to drink.

7.3 Identifying preschool children in need of dental care

Identification of dental caries at an early stage is highly desirable if preventive measures and restorative care are to be successful. Many parents are under the misapprehension that they do not need to take their child for a dental check-up visit until age 4 or 5 years. Up to the end of the 1990s, the Community Dental Service in the UK (previously the School Dental Service) provided dental screening in schools. This often identified untreated caries in children who had not already had their first dental check-up. However, in recent years regular screening for dental disease in UK schools has been radically reduced or, in some areas, has ceased altogether, removing this ‘safety net’. Therefore it is more important than ever that parents understand the need to seek oral health assessment for their children from an early age.

Parents should be encouraged to bring their child for a dental check (oral health assessment) as soon as he/she has teeth, usually around 6–12 months of age. This allows appropriate preventive advice regarding tooth-cleaning, fluoride toothpastes, and the avoidance of inappropriate bottle habits. It also allows the child to become familiar with the dental environment and enables the dentist to identify any carious deterioration of the teeth at an early stage. Other health professionals, such as health visitors, can also be valuable in delivering key preventive advice and helping to identify young children with possible decay. Hence making contact with local health visitors and delivering dental health messages via mother and toddler groups can be useful strategies. Recent guidelines published by the Department of Health, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) (see References) are valuable resources and provide information in a form suitable for sharing with other health professionals. (See Key Points 7.3.)

7.4 Management of pain at first attendance

Unfortunately, the preschool child with caries has often already experienced pain when he/she first attends a dental surgery. Not only does this present the immediate problem of having to consider active treatment in a very young inexperienced patient, but also these problems are often compounded by the child’s lack of sleep and the time constraints on the dentist.

Pulpitis can sometimes be effectively managed, in the short term, by gentle excavation of caries and dressing with a zinc oxide and eugenol based material, such as IRM (intermediate restorative material). Poly-antibiotic and steroid pastes (e.g. Ledermix) may be useful beneath such dressings, and over/near exposure of the pulp.

The pulp chamber of abscessed teeth can sometimes be accessed by careful hand excavation, in which case placing a dressing of polyantibiotic paste on cotton wool within the pulp chamber will frequently lead to resolution of the swelling and symptoms. An acute and/or spreading infection or swelling may require the prescription of systemic antibiotics, although there is little rationale for the use of antibiotics in cases of toothache without associated soft tissue infection/inflammation.

Dental infection causing significant swelling of the face, especially where the child is febrile or unwell, constitutes a dental emergency and consideration should be given to referral to a specialized centre for immediate management. (See Key Points 7.4.)

7.5 Principles of diagnosis and treatment planning for preschool children

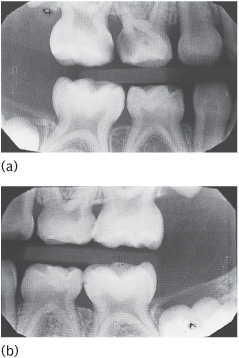

When planning dental treatment for preschool children, it is important to appreciate that dental caries of enamel is essentially a childhood disease and that progression of caries in the primary dentition can be rapid. Therefore early diagnosis and prompt instigation of appropriate treatment is important. Preschool children should be routinely examined for dental caries relatively frequently (at least two or three times per year). More frequent examination (e.g. every 3 months) may be justified for children in high-risk groups. Approximal caries is common in primary molars so, in children considered to be at increased risk of developing dental caries and where posterior contacts are closed, a first set of bitewing radiographs should be taken at 4 years of age, or as soon as practically possible after that (Fig. 7.4). In such children consideration should be given to repeating bitewings at least annually in the first instance. (See Key Points 7.5.)

7.6 Preventive care

Preventive measures are the cornerstone of the management of dental caries in children. There is often a failure to appreciate that those aspects of care we refer to as prevention are actually a fundamental part of the treatment of dental caries. Repairing the damage caused by dental caries is also important, but this will only be successful if the causes of that damage have been addressed. A good analogy is that of a burning house. Repairing the house (new windows, roof, furniture, etc.) is important, but all this will be of little benefit in the long term if the fire has not been put out! A structured approach to prevention should form a key part of the management of every preschool child. In the UK, a number of published guidelines focusing on the prevention of oral disease provide an invaluable resource (SIGN 2000, 2005; Department of Health 2009; SDCEP 2010). (See Key Point 7.6.)

Figure 7.4 (a) Right and (b) left bitewing radiographs of a 4-year-old child. The caries in the upper right molars would be clinically obvious but the early approximal lesions in the lower left molars would not. Bitewing radiographs not only enable an accurate diagnosis, but also allow early lesions to be compared on successive radiographs to enable a judgement to be made about caries activity and progression.

7.6.1 Fluorides

Self-administered

Fluoride toothpaste

Parents should be advised to start brushing their child’s teeth with a fluoride toothpaste as soon as the first tooth erupts, at around 6 months of age. A toothpaste containing 1000ppm fluoride should be advised for children considered to be at low risk of developing caries. Toothpastes with a lower fluoride concentration may be justified in areas receiving fluoridated water supplies, but the available evidence suggests that sub-1000ppm toothpaste has little or no caries-preventive effect if other sources of fluoride are not available. In the UK, the Department of Health now supports prescribing toothpastes containing higher concentrations of fluoride (i.e. 1350–1500ppm) to preschool children deemed to be at higher risk of developing caries, irrespective of their age. Where higher concentration toothpastes are prescribed for preschool children, parents should be counselled to ensure that brushing is supervised (see Section 7.6.4), small amounts of toothpaste are applied to the brush (up to 3 years a ‘thin smear’; 3 years and above a ‘small pea-size blob’), and that children spit out as well as possible (but avoid rinsing) after brushing. (See Key Point 7.7.)

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Key Points 7.1

Key Points 7.1

Key Points 7.2

Key Points 7.2 Key Points 7.3

Key Points 7.3 Key Points 7.4

Key Points 7.4 Key Points 7.5

Key Points 7.5 Key Point 7.6

Key Point 7.6

Key Point 7.7

Key Point 7.7