Orthodontics

Learning Outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the student will be able to achieve the following objectives:

• Pronounce, define, and spell the Key Terms.

• Describe the environment of an orthodontic practice.

• Describe the types of malocclusion.

• Discuss corrective orthodontics, and describe what type of treatment is involved.

• List the types of diagnostic records that are used to assess orthodontic problems.

• Describe the components of the fixed appliance.

Performance Outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the student will be able to achieve competency standards in the following skills:

• Place and remove steel separating springs.

• Place and remove elastomeric ring separators.

• Assist in the fitting and cementation of orthodontic bands.

• Assist in the direct bonding of orthodontic brackets.

Electronic Resources

![]() Additional information related to content in Chapter 60 can be found on the companion Evolve Web site.

Additional information related to content in Chapter 60 can be found on the companion Evolve Web site.

• Interactive Dental Office Patient Case Study: Kevin McClelland

• Procedure Sequencing Exercises

• WebLinks

Key Terms

Arch wire A contoured metal wire that provides force when teeth are guided in movement for orthodontics.

Auxiliary (awg-ZIL-yuh-ree) Attachments located on brackets and bands that hold arch wires and elastics in place.

Band Stainless steel ring attached to molars to hold the arch wire and auxiliaries for orthodontics.

Braces Another term for fixed orthodontic appliances.

Bracket A small device bonded to teeth to hold the arch wire in place.

Cephalometric (seph-uh-loe-MET-rik) radiograph An extraoral radiograph of the bones and tissues of the head.

Cross-bite Condition that occurs when a tooth is not properly aligned with its opposing tooth.

Crowding Condition that occurs when teeth are not properly aligned within the arch.

Dentofacial Structures that include the teeth, jaws, and surrounding facial bones.

Distoclusion (dis-toe-KLOO-shun) A class II malocclusion in which the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar occludes mesial to the mesiobuccal groove of the mandibular first molar.

Ectopic An abnormal direction of tooth eruption.

Fetal molding Pressure applied to the jaw, causing a distortion.

Headgear An external orthodontic appliance that is used to control growth and tooth movement.

Ligature (LIG-uh-chur) tie Light wire used to hold the arch wire in its bracket.

Mesioclusion (mee-zee-oe-KLOO-zhun) Term used for class III malocclusion.

Open bite A lack of vertical overlap of the maxillary incisors, creating an opening of the anterior teeth.

Orthodontics (or-thoe-DON-tiks) Specialty of dentistry designed to prevent, intercept, and correct skeletal and dental problems.

Overbite Increased vertical overlap of the maxillary incisors.

Overjet Excessive protrusion of the maxillary incisors.

Positioner An appliance used to retain teeth in their desired position.

Retainer An appliance used for maintaining the positions of the teeth and jaws after orthodontic treatment.

Orthodontics is the specialized branch of dentistry that diagnoses, prevents, and treats dental and facial irregularities. Orthodontics includes dentofacial orthopedics, which is a term used when a fixed or removable appliance is positioned inside or outside the mouth to correct problems that involve movement of teeth or growth of the jaws.

Orthodontic treatment includes the following types of treatment:

• Straightens teeth that are rotated, tilted, or otherwise improperly aligned

As insurance companies increase their benefits for continued orthodontic care, more people will choose orthodontic treatment throughout their lifetime, at any age.

Benefits of Orthodontic Treatment

Orthodontic treatment can eliminate or reduce adversity for the patient in three areas: psychosocial problems, oral malfunction, and dental disease.

Psychosocial Problems

Severe malocclusion and dental facial deformities can be a social handicap. The impact of these types of problems may have a strong influence on patients’ self-esteem and their positive feelings about themselves.

Oral Malfunction

Dental Disease

Malocclusion can contribute to dental decay and periodontal disease. When the teeth and tissues do not receive the benefits of normal occlusion and natural cleansing, proper plaque removal becomes difficult.

The Orthodontist

The orthodontist works closely with the pediatric and general dentist in providing an opportunity to change a person’s “smile.” As a specialist, the orthodontist will continue his or her education after dental school. Most accredited orthodontic programs are 3 years in length. The emphasis of study for the orthodontist is with orofacial growth and development, new techniques, biomechanics, and research. After receiving a certificate or a master’s degree, the orthodontist will go into private practice or remain in academia.

The Orthodontic Assistant

If you are looking for an area of dentistry with greater autonomy, orthodontics is the specialty of choice. The orthodontic assistant has the ability to participate in many “hands-on” skills. Depending on the expanded functions that are legally permitted in the state in which you practice, the clinical assistant is able to participate in various procedures, which involve diagnostic records, preliminary appointments, and adjustment visits.

If advancing in the profession of orthodontics is your goal, you have opportunities to (1) continue specialized training within a program, or (2) take the Dental Assisting National Boards specialty examination in Orthodontic Assisting to obtain an additional credential of certified orthodontic assistant (COA).

The Orthodontic Office

The orthodontic office is designed to accommodate many patients at a time. Because very little equipment is required for orthodontic procedures, the orthodontic office follows the “open bay” concept, along with pediatric dentistry. The patient care area of the office can be sectioned off to serve three functions: (1) to obtain records and create a more private setting, (2) to take radiographs, and (3) to provide clinical care at all stages of treatment. In larger practices, it is common to see up to 30 patients a day. Longer appointments, such as obtaining records or the bonding of brackets, are scheduled in the morning and early afternoon; shorter appointments, such as adjustments and emergencies, are kept for the early morning and late afternoon.

One area of the practice that can be more expansive in the orthodontic setting is the dental laboratory. Some orthodontic practices fabricate their own diagnostic casts and fixed and removable appliances to keep overhead costs down. If a staff member has that artistic capability, this work can be profitable for that person.

Understanding Occlusion

Most malocclusions are caused by hereditary factors that affect the contours of the face and the size of the teeth and jaw. The most common cause of malocclusion is a disproportion in size between the jaw and the teeth or between the upper and lower jaws. Orthodontic problems result from the interaction of developmental, genetic, and environmental influences.

Developmental Causes

Disturbances in dental development can accompany major congenital defects; however, they occur more frequently as isolated findings. The most commonly encountered developmental disturbances include the following:

Genetic Causes

Genetic causes are responsible for malocclusion when discrepancies in the size of the jaw and/or the size of the teeth are evident. A child who inherits a mother’s small jaw and a father’s large teeth may have teeth that are too big for the jaw, causing overcrowding. If you have a missing tooth, it is likely that one of your parents or grandparents has the same missing tooth.

Environmental Causes

Birth Injuries

Injuries can occur at birth in two major categories: fetal molding and trauma during birth.

Injury Throughout Life

Trauma to the teeth can occur throughout life. Dental trauma can lead to the development of malocclusion in three ways:

Habits

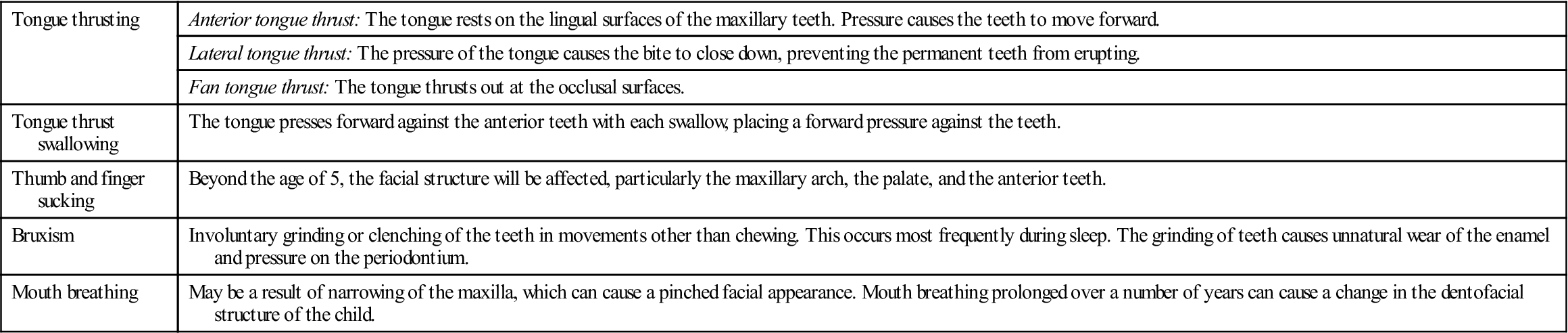

Habits that contribute to malalignment must be corrected if orthodontic treatment is to be successful. As a general rule, sucking habits that involve the thumb, tongue, lip, or finger during the primary dentition years are considered normal. These habits have few, if any, long-term effects beyond the mixed dentition; however, if they persist beyond this stage, it may be necessary to seek guidance in eliminating the habit. Table 60-1 describes habits that affect the dentition.

TABLE 60-1

Habits That Affect the Dentition

< ?comst?>

| Tongue thrusting | Anterior tongue thrust: The tongue rests on the lingual surfaces of the maxillary teeth. Pressure causes the teeth to move forward. |

| Lateral tongue thrust: The pressure of the tongue causes the bite to close down, preventing the permanent teeth from erupting. | |

| Fan tongue thrust: The tongue thrusts out at the occlusal surfaces. | |

| Tongue thrust swallowing | The tongue presses forward against the anterior teeth with each swallow, placing a forward pressure against the teeth. |

| Thumb and finger sucking | Beyond the age of 5, the facial structure will be affected, particularly the maxillary arch, the palate, and the anterior teeth. |

| Bruxism | Involuntary grinding or clenching of the teeth in movements other than chewing. This occurs most frequently during sleep. The grinding of teeth causes unnatural wear of the enamel and pressure on the periodontium. |

| Mouth breathing | May be a result of narrowing of the maxilla, which can cause a pinched facial appearance. Mouth breathing prolonged over a number of years can cause a change in the dentofacial structure of the child. |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Malocclusion

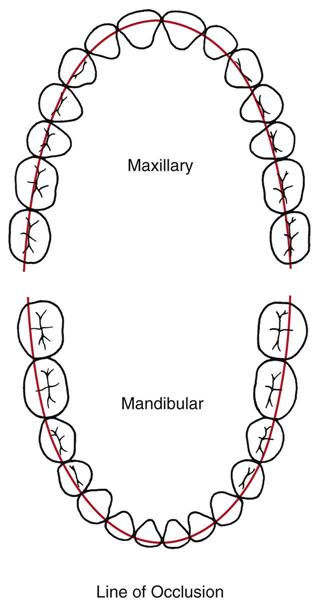

As described in Chapter 11, the maxillary and mandibular teeth, when closed correctly, are referred to as being occluded or as having normal occlusion (Fig. 60-1).

Orthodontists are concerned with teeth that do not occlude properly because of the size of the patient’s jaws, or because of crowding or displacement of teeth. Malocclusion refers to the abnormal or malpositioned relationship of the maxillary teeth to the mandibular teeth when occluded.

According to Angle’s classification, any deviation from normal occlusion is regarded as malocclusion.

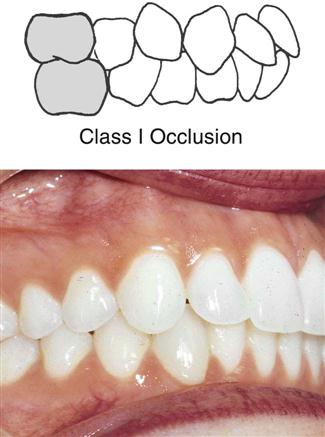

Class I Malocclusion

Class I malocclusion consists of a normal relationship with the molars, but the anterior teeth will be out of alignment with malpositioned or rotated teeth (Fig. 60-2).

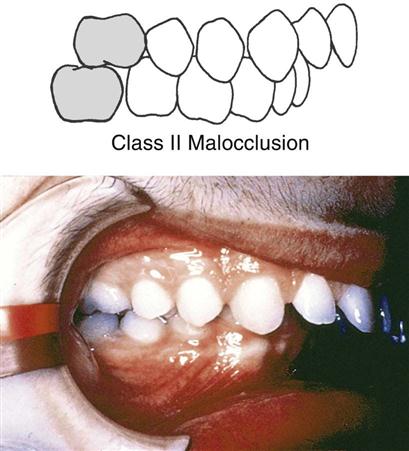

Class II Malocclusion

In class II malocclusion, also known as distoclusion, the mandible is in an abnormal distal relationship to the maxilla. The mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar occludes in the interdental space between the mandibular second premolar and the mesial cusp of the mandibular first molar. This gives the appearance of the maxillary anterior teeth protruding over the mandibular anterior teeth. A common lay term for this condition is buckteeth (Fig. 60-3).

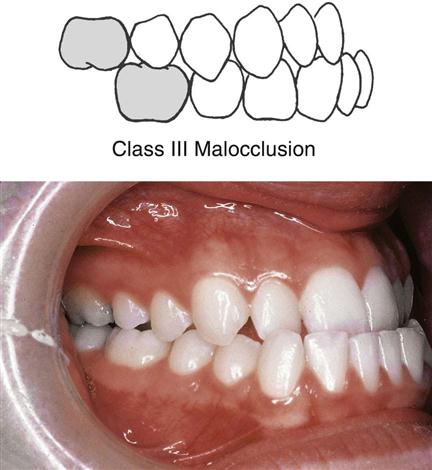

Class III Malocclusion

In class III malocclusion, also known as mesioclusion, the body of the mandible is in an abnormal mesial relationship to the maxilla. The mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar occludes in the interdental space between the distal cusp of the mandibular first permanent molar and the mesial cusp of the mandibular second permanent molar. This frequently gives the appearance of the mandibular anterior teeth protruding in front of the maxillary anterior teeth, also referred to as an underbite (Fig. 60-4).

Malaligned Teeth

In addition to evaluating a patient’s occlusion, the orthodontist examines specific alignment of the teeth and arches. The most common malalignment problems are as follows:

• Crowding is the most common contributor to malocclusion. One or many teeth can be involved in misplacement (Fig. 60-5).

• Overjet is excessive protrusion of the maxillary incisors, causing space or distance between the facial surface of the mandibular incisors and the lingual surface of the maxillary incisors (Fig. 60-6).

• Overbite is an increased vertical overlap of the maxillary incisors. With an extreme overbite, the mandibular incisors may not be visible (Fig. 60-7).

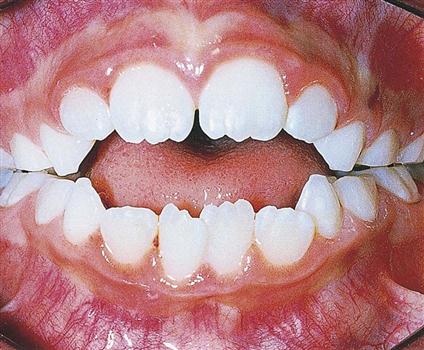

• Open bite is a lack of vertical overlap of the maxillary incisors, creating an opening of the anterior teeth when the posterior teeth are closed (Fig. 60-8).

• Cross-bite indicates that a tooth is not properly aligned with its opposing tooth. An example of this occurs when a person closes the teeth; the maxillary arch should be slightly wider and longer so that it properly occludes the mandibular arch. If a maxillary tooth is inward or touches end to end with another tooth, then a cross-bite exists (Fig. 60-9).

Management of Orthodontic Problems

Pediatric and general practitioners are trained in the recognition and treatment of preventive and interceptive orthodontic cases (see Chapter 57 for information on preventive and interceptive care). More extensive cases, however, are referred to the orthodontist for diagnosis and treatment.

Corrective Orthodontics

The scope of corrective orthodontics includes conditions that require the movement of teeth and the correction of malrelationships and malformations. Adjustments between and among teeth and facial bones are made through the application of fixed appliances with force and sometimes through stimulation and redirection of functional forces within the dentofacial structure. Responsibilities of personnel in the orthodontic practice include treatment of all forms of malocclusion of the teeth and surrounding structures.

Orthodontic Records and Treatment Planning

The first step in determining a treatment plan is for the orthodontist to learn as much about the orthodontic condition as possible. The patient’s first orthodontic appointment will be devoted to obtaining records. These records are needed for the orthodontist to make a diagnosis and devise a treatment plan.

Medical and Dental History

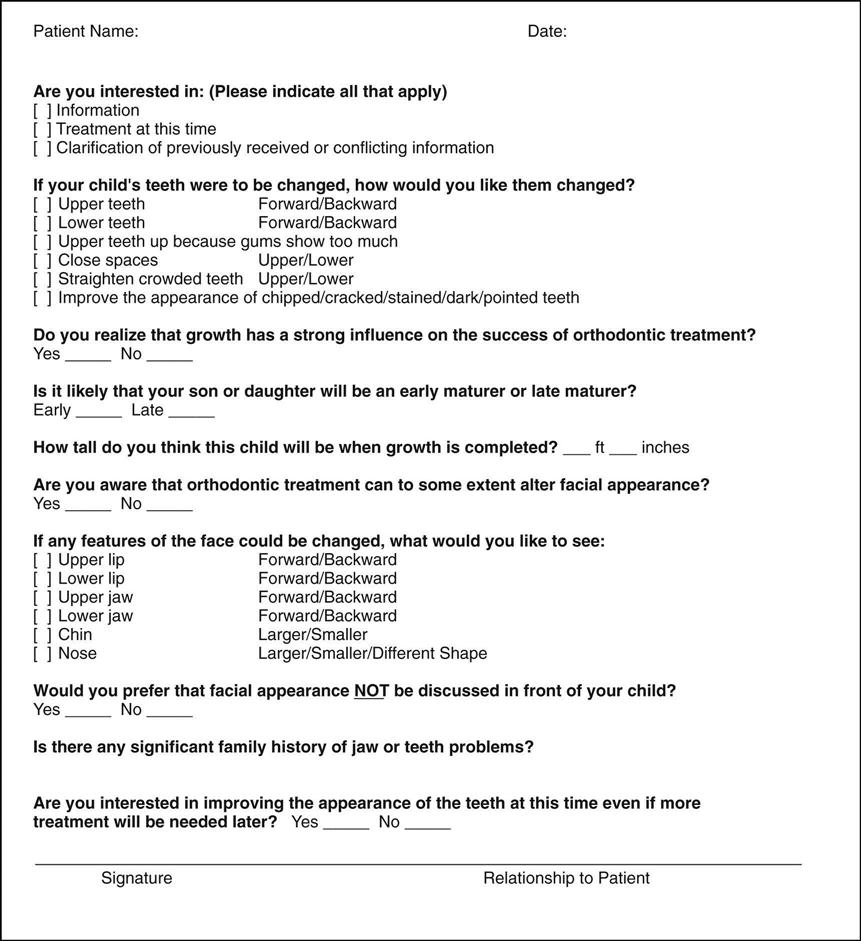

Careful medical and dental histories are necessary to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the physical condition and to evaluate specific orthodontic concerns (Fig. 60-10).

Physical Growth Evaluation

Because orthodontic treatment in children is closely related to growth stages, it is necessary to evaluate the child’s physical growth status. Questions are asked about how rapidly the child has grown recently and about signs of sexual maturation.

Social and Behavioral Evaluation

Motivation for seeking treatment is very important. What does the patient expect as a result of treatment? How cooperative or uncooperative is the patient likely to be? A major motivation for orthodontic treatment of children is the parent’s desire for treatment; however, it is essential that the child be willing and cooperative. The typical child accepts orthodontic treatment in a positive way.

Adults tend to seek orthodontic treatment for themselves for other reasons, including the need to improve personal appearance or function of the teeth. It is important to explore the reasons why an adult patient seeks treatment.

Clinical Examination

The purpose of the orthodontic clinical examination is to document, measure, and evaluate the facial aspects, the occlusal relationship, and the functional characteristics of the jaws. At the initial (records) visit, the orthodontist decides which diagnostic evaluations are required for the patient.

Analysis of Facial Proportions

A reasonable goal for orthodontic treatment is to recognize and improve facial symmetry by correcting disproportion (Fig. 60-11).

In frontal analysis, the face is examined for the following:

In the profile analysis, the profile relationship is examined for the following reasons:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses