CHAPTER 6

IMPLEMENTATION OF HEALTH BEHAVIOR CHANGE PRINCIPLES IN DENTAL PRACTICE

Key Points of This Chapter

- The environment of oral care delivery has unique challenges and opportunities when promoting health behavior change.

- The patient activation model for the dental visit represents interwoven strands of the visit structure with techniques that can promote behavior change.

- Implementation complements, rather than complicates, the existing structure of the oral care appointment.

The previous chapters of this book have described various elements of health behavior change from both the theoretical and practical perspective. Comparisons have been presented highlighting that health behavior change is not so dissimilar from our encounters with change in everyday life. As much as knowledge and understanding may have been increased or solidified as a result of reading the previous chapters, taking this information further into everyday practice may require some additional steps. This chapter will focus on some of the practical elements to consider as you continue to incorporate health behavior change approaches into your clinical practice.

Changing clinical practice carries some unique challenges. Recognition of this has, in turn, stimulated research in the area to provide further guidance on managing change in clinical work settings. Change management theory suggests that successful transformation is a result of the interaction between the content of change (objectives), the context of change (environment), and the process of change (implementation plan), and incorporates identification of barriers as a key element contributing to successful change (Dawes 1999; Pettigrew et al. 1989). In this chapter, the implementation of behavior change principles in the dental practice will be discussed within this framework of headings: content (objectives), context (environment), process (implementation plan), and barriers.

Most clinicians will be aware that the promotion of health behavior changes with the patients in their care may provide a range of benefits —increased success of treatment outcomes, decreased incidence of disease, increased confidence for both patient and clinician. Increasingly, as a growing percentage of the population are diagnosed with health decline that is often associated with “lifestyle” behaviors, the health professional is often required to have a dual focus—control of current disease while facilitating continuous self-management as part of an effective long-term solution. Oral health professionals are not exempt from this approach to patient care as we continue our efforts to manage disease and support health behavior change. The move from treating the disease (extraction, restoration, and gingivectomy) to minimally invasive dentistry and core preventive modalities reflects the impact of the growing change of focus in oral health care. More and more, we understand that regular, effective oral hygiene measures, cessation of tobacco use, management of alcohol consumption, and dietary control can contribute significantly to the reduction of risk for the developmeelopment of diseases such as dental caries, periodontal disease, and oral cancer (Ramseier 2005). All of these elements may be within the capabilities of a positive union of professional support and continuous self-management by the patient.

The clinical encounter provides an opportunity for clinicians to develop a supportive, professional relationship that engages the patient in a dialogue about possible changes in health behaviors. This opportunity is often under-utilized. While some clinicians may find that applying health behavior change strategies or approaches is easy and natural, for others it may be more difficult. They may be more comfortable with the “traditional” role of the health professional as the expert provider of knowledge and advice to the patient. Indeed, the patient may also be accustomed to the role of “being told what to do” without complete understanding of why or indeed how to achieve the expectations of the clinician. Herein lies the dilemma in the clinician patient relationship as they work together toward improved health and reduced disease—how can they understand each other? This chapter aims to provide a discussion framework for further exploration with your patients as you work together to develop an optimal plan of care for improved oral health.

The environment of oral care delivery has unique challenges and opportunities when promoting health behavior change.

Content of change (the objectives)

If you encounter only patients with very low plaque scores, without periodontal disease, without caries, non-smokers, of normal weight, then you probably need not read further other than for sheer curiosity. However, many clinicians are often presented with care scenarios that reflect a plethora of multi-layered considerations from both a physiological (biological) and psychological (behavior) aspect. Both of these elements impact substantially on the adaptation required to maximize an effective communication pathway that may lead to supporting behavioral change. For experienced and inexperienced clinicians alike, the following examples are all too familiar:

The woman who attends for continuous restorative dental care proclaiming that, “My mother had bad teeth, so I guess I have her genes.”

The man who comes to the practice for his maintenance visit presenting yet again with poor oral hygiene and the resulting consequences but this time comes with the demand for dental implants, as his friend has just received them.

The patient who validates his lack of self- management by stating, “If I just come to see you regularly then everything will be okay.”

Clinicians are often bewildered that some patients seem so motivated and compliant while others seem less than motivated or even non-responsive in spite of the same messages being delivered with somewhat the same enthusiasm in all situations. They may find themselves influenced by previous successes, applying solutions that worked with some patients when advising other patients. With persistence, using trial and error strategies, sooner or later many patients make lifestyle or self-care changes according to clinician recommendations. This could be due to the rapport that develops over time between the clinician and patient. In many cases, change is influenced by factors outside of the dental environment such as family, friends, media reports, or as a result of a series of other lifestyle changes. Just as common dental diseases are often multi-factorial in nature, change is often a cumulative process that builds a reasonable argument that can be accepted by the patient. If that argument is skillfully drawn from the patient as his or her own idea, then the reasons to change become more attractive. Therefore, if any of your patients could benefit from changes in self-care behaviors, the next step may be to consider how you feel about attempting to enhance your impact on the process.

Context of change (the environment)

When considering implementation of behavior change approaches, the context or environment is characterized by many elements, from attitudes, perceptions, past events, and current events to simply the physical space that you work in. It is important not to limit or underestimate the number of factors and their influence. Two particular factors related to perception are worthy of mention as we progress to consider context further.

Self-perception of our role as an oral health professional plays an important part in taking new steps to “activate” our patients. Traditionally, we may have been clinicians rendering technical procedures as interventions for disease treatment. Therefore, once a disease was defined, a treatment paradigm resulted thereafter. More recent knowledge of the chronic nature of diseases and multiple factors affecting them has brought focus on prevention and wellness. This knowledge has put disease management into a broader context. In recent times, we have seen that health professionals function in a much broader role as we think about health behavior change. In essence, clinicians may function as a type of “health coach” for chronic condition self- management in addition to providing treatment.

With easy access to a vast supply of information forms via the internet, many of our patients are increasingly independent in their health understanding, thoughts, and goals. As a result, the perspective of patients should always be considered a key element in the development of an ongoing plan of care. What is their perceived treatment need? Is it the same as their actual treatment needs? Understanding our patients’ perspective of disease and health or their perception of our role is vital to our approach in conversing with them. Are they expecting us to “fix” or “cure”? Are they aware that much of dental care today is targeted toward prevention or complex disease management? The alignment of the clinician and patient in regard to the context of health care goals is paramount to supporting positive outcomes.

Process of change (the implementation plan)

You may be in a situation with extensive schedule flexibility, allowing you to spend lengthy amounts of time in discussion with your patients, or alternatively you may be bound to tight schedules with brief amounts of time. Regardless of the length of the visit, successful interactions are realistic. Remember the key lies in the approach.

There are many different ways to implement and integrate the approaches outlined in the previous chapters into daily practice. Implementation will depend on a variety of factors, most of which you will be the best person to identify. Above all, it is important to remember that behavior change strategies are designed to make your life easier. Approaches to the exploration of a patient’s health behaviors can be a valuable learning experience for all. By exploring all the options for behavior change, the clinician and patient may discover new, effective solutions to concerns that were once regarded as unmanageable. In turn, the successes of each approach will increase confidence to address other issues or concerns for the patient and clinician. The wise proverb of “Success breeds success” is highly applicable to the field of improving oral health through behavior change.

Conversely, without exploration and understanding of the patient’s intrinsic sense of change, the clinician often becomes bound to the “one- way traffic” conversation of advising and sometimes scolding. To repeat the same instructions can be frustrating for patient and clinician alike. It is akin to the definition of insanity; namely, doing the same thing and expecting a different result. In addition, this frustration may lead to resentment that can damage further relationship development. Herein lies the challenge of engagement toward success that is meaningful for the clinician and patient.

In reviewing the dental professional’s content, context, and process for making even the smallest change in his or her own techniques or approaches, it is helpful to consider a perspective of the micro-environment, that is, the dental visit with an individual patient, and the macro-environment, referring to the overall practice setting or ethos.

MICRO-ENVIRONMENT: THE DENTAL VISIT

Easier than you think

The patient activation model for the dental visit represents interwoven strands of the visit structure with techniques that can promote behavior change.

As we consider the scenarios at the beginning of this chapter, the question of where to start re- emerges. By focusing on a simple strategy based on the key underlying principles presented in the previous chapters, getting started can be easier than you think.

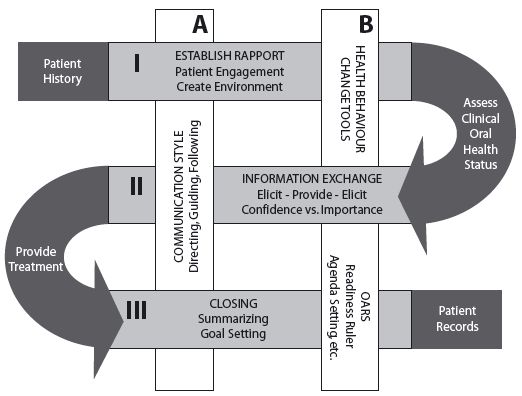

Use of a model designed specifically to guide dental clinicians in the exploration of integrating behavior change principles into everyday practice is presented for discussion (see Figure 6.1). The model depicts the “fabric” of the average health behavior change -focused dental visit. This fabric represents interwoven strands of the visit structure with techniques that can promote behavior change.

Patient activation fabric for the dental visit (implementation model)

The clinical dental visit is multi-layered and multi-functional. This model attempts to capture the interdependent elements of the visit using the concept of interwoven threads. Communication and information exchange blend together with clinical assessment and treatment. Thus, the success of the resulting “fabric” of the care plan is dependent on the interwoven strength of each thread (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1. Patient activation fabric for the dental visit (implementation model).

The horizontal bands depict the three core strands of conversations constituting the visit. These bands transition directly into the curves, representing the clinical assessment or treatment that takes place between the conversations as part of the flow of the appointment. The bands are woven together through the vertical ribbons that signify the specific elements of the communication and interaction characterizing the approach. These vertical ribbons are consistent, yet flexible, recurring throughout the fabric, ready to provide stability as the horizontal bands are maneuvered around at each dental visit. The patient history and patient’s records positioned at the start and end depict the critical elements of documentation that serve to weave one visit into the next.

Band I: Establish rapport

This is the opening part of the appointment. The goal is to quickly engage the patient and establish an open rapport. Accomplishing this depends on approach much more than the amount of time taken. A warm, courteous greeting is a critical start in creating an environment of mutual trust and respect. Ensuring that this initial greeting includes eye contact at the same level (i.e., both standing or both seated, and not when the patient is supine) will further support a comfortable environment. These simple actions create the perception of the patient and clinician having equal control of the situation rather than one being dominant. Having a sense of control can generate significant confidence, as the patient feels he or she has a valid role in the process of the appointment. This feeling of autonomy and confident collaboration, rather than passive observation, can greatly assist in patient activation that engages intrinsic motivation.

Implementation complements, rather than complicates, the existing structure of the oral care appointment.

Beginning with an open question that seeks the patient’s prime concern or reason for attending the visit is another simple and valuable step. These opening moments set the scene for the remainder of the visit and can save you valuable time later in the session. For example, starting with the patient’s concerns can allow you to detect potentially relevant clinical signs to inform your assessment. In addition, paying attention to this step communicates to your patient that you are interested in him or her as a person, making it easier at later stages of the visit to initiate brief conversations about change.

Before proceeding with the clinical assessment, it is important to briefly list the elements of the procedure to patients, then ask them if they would be happy for you to proceed with it at that time. Asking permission is a simple way to engage the patient while simultaneously encouraging a sense of autonomy. It may be helpful to explain to the patient the relevance of the information that he or she may hear you give to your assistant. These small actions help to keep your patient engaged in the consultation, rather than allowing the patient to shift to a passive role of lying helplessly throughout the assessment procedure. For example, before an assessment of probing pocket depth, the clinician may ask the patient what he or she knows about the range of measurements. The clinician can go on to clarify to the patient the range of measurements considered to be in “health.” When the patient hears the clinician reporting any probing depths beyond the healthy range, he or she may understand that there is a potential breakdown of health. This can generate a valuable discussion, after the assessment, initiated by the patient with regard to periodontal health. Using this approach, the patient is actively asking for information. This may then lead to further requests for information or advice on self- care strategies for home.

Band II: Information exchange

This second band or portion of the interaction between clinician and patient would most often take place following initial clinical assessment of the patient‘s oral health status. It is likely the primary time for informing, although both you and your patient will seek and provide information throughout the visit. This exchange allows both parties to understand the other’s perspective and create a more accurate picture of the clinical problem and approaches to effective management. This discussion can take many different forms. Through the lens of more traditional models, the practitioner may take an “expert” role, asking a series of closed clinical questions, which the patient is required to answer. The limitations of this approach have been discussed elsewhere in this book. Most noteworthy, however, is the effect this has on reinforcing passivity in the patient.

An alternative approach to providing information is one in which the practitioner maintains a focus on patient engagement. A valuable point in thinking about ways to do this is to remember that when talking to your patient, you are talking to an expert! No one knows his or her disease and life context better than the patient him- or herself. A simple framework for information exchange has been suggested to help you introduce new information in a guiding style of communication (Rollnick et al. 2007). The/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses