6

Hypnosis in dentistry

In the short time that it takes you to read this chapter, you will discover, as I did, some of the most powerful and practice-changing skills you can learn as a dentist.

You will discover some of the science behind hypnosis and also some hypnotic techniques that can be easily and effectively applied when managing anxious patients in a busy modern dental office.

This chapter will be an introduction for those who are new to dental hypnosis and will start a journey of exploration and expansion. For those who already know about hypnosis through previous training or reading, I hope it will introduce a few new concepts, techniques, and ideas, and perhaps also remind you about a few things that you have forgotten you knew.

Moss1 defines hypnodontics as “that branch of dental science which deals with the application of controlled suggestion and hypnosis to the practice of dentistry.”

This description from nearly 60 years ago identifies the fact that hypnosis in dentistry is far more than just the “formal” aspects and traditional ideas of hypnosis that most commonly come to mind.

In fact, the chapter from which the quote above is taken from, entitled “Hypnodontics Today,” describes how suggestion plays a very important role in the dentist/patient relationship, from when the patient first “hears about the dentist at his bridge club” to the type of doorbell at the office, the appearance of the waiting room, the greeting of the dental assistant, the personal appearance of the dentist, the quality of his voice, his mannerisms—all of which are types of “suggestions.” Gabor Filo (in Chapter 7 of Brown et al.2) offers “A Validation for Hypnosis in Dental Practice,” addressing how hypnosis can be integrated into twenty-first century dentistry alongside rapidly advancing technology.

When studying hypnosis, practitioners are taught many techniques for effectively using suggestion, as well as other skills, such as rapport building, language, and communication skills, etc., that can then also be applied in everyday situations. Many who have trained in hypnosis and studied the work of Dr. Milton Erickson (see Rosen3 and Rossi4) will tell you that the day-to-day “informal” uses of hypnotic principles are probably the most important clinical skills that you can ever learn and develop. Kirsch et al.5 highlighted that “hypnotic and waking responses to the same suggestions are highly correlated, and the difference between them is relatively small.” This concept has long been known; in fact, Stolzenburg6 stated, “The practitioner who is competently trained in hypnosis will find that there is a diminished need for the use of hypnosis per se, with most of his patients.” These techniques are especially invaluable in the initial therapeutic consultation with a fearful or phobic patient.

Kay Thompson once said, “My words are the chisels, the brushes used to attempt to reach the inner block of material, the canvas of the individual, modifying the story as the cues demand, and waiting for the message that change is ready, leaving the creation to be interpreted by the patient, the one who commissioned the vision in the beginning.”7

Hypnosis is very effective in managing appropriate cases, and is often used most effectively when in combination with traditional techniques, complementing conscious sedation for example.

The “father of modern medical hypnosis” himself, Dr. James Braid, recognized his concept very early on and stated: “I consider the hypnotic mode of treating certain disorders is a most important ascertained fact, and a real solid addition to practical therapeutics, for there is a variety of cases in which it is really most successful, and to which it is most particularly adapted; and those are the very cases in which ordinary medical means are least successful, or altogether unavailing. Still, I repudiate the notion of holding up hypnotism as a panacaea or universal remedy. As formerly remarked, I use hypnotism ALONE only in a certain class of cases, to which I consider it peculiarly adapted—and I use it in conjunction with medical treatment, in some other cases; but, in the great majority of cases, I do not use hypnotism at all, but depend entirely upon the efficacy of medical, moral, dietetic, and hygienic treatment, prescribing active medicines in such doses as are calculated to produce obvious effects” (emphasis added).8

Hypnosis has been used for medical purposes in various guises for thousands of years. See Gauld9 for a detailed history of hypnosis, and Chaves10 for an overview of the history of hypnosis in dentistry. Certainly, Egyptians and Greeks are known to have gone to “Sleep Temples” to be healed by priests. Prior to the advent of reliable chemical anaesthesia, British medical surgeons such as Elliotson, Esdaile, and Braid pioneered the use of hypnotic techniques in controlling the pain and anxiety associated with medical surgery in the nineteenth century.11,12 At this time, there was growing interest, and there were many theories such as “animal magnetism,” or mesmerism. Dr. James Braid, a Scottish physician-surgeon working in Manchester, England, was the first to challenge these theories, and believed that the phenomena could be induced by suggestion and fixed mental concentration without the use of magnets. Braid,12 who promoted his theories as early as 1841, ultimately adopted the term “hypnotism” (derived from hypnos or “hupnos,” the Greek word for sleep). The terms hypnotique, hypnotisme, hypnotiste had previously been used by the French magnetist Baron Etienne Félix d’Henin de Cuvillers (1755–1841) around 1820, but Braid was the first to use the terms hypnotism, hypnotize, and hypnotist in English and to attribute the phenomena to psychology.13 Braid himself, however, soon realised that “hypnotism” was quite different from his original sleep-based physiological theory, and came to favor the terms “neurohypnology,” “braidism,” or “monoideism” (mental concentration on a single idea) (p. 108).13 “Hypnotism” and “hypnosis,” however, were already popular terms and had become recognized across the world.

Over the years, there has been much debate as to how to define hypnosis and by what mechanisms it actually works. Essentially, hypnosis can be considered as either a mental state (state theory) or a set of attitudes and beliefs (nonstate theory). Some believe that hypnosis is an “altered state of consciousness” marked by changes in the way the brain functions. Others believe that hypnotized subjects are actively motivated to behave in a hypnotic manner and are not simply passively responding to hypnotic suggestions. There are many theories and models of hypnosis that are beyond the scope of this chapter; however, readers wishing to study these can easily find them in several books and resources (e.g., Lynn and Rhue,14 Kirsch and Lynn,15,16 Gruzelier,17 Oakley,18 Rossi,19 Chapter 7 in Heap et al.,20 Nash and Barnier,21 and Brown and Oakley).

The American Psychological Association (APA) definition for hypnotism is:

Hypnosis typically involves an introduction to the procedure during which the subject is told that suggestions for imaginative experiences will be presented. The hypnotic induction is an extended initial suggestion for using one’s imagination, and may contain further elaborations of the introduction. A hypnotic procedure is used to encourage and evaluate responses to suggestions. When using hypnosis, one person (the subject) is guided by another (the hypnotist) to respond to suggestions for changes in subjective experience, alterations in perception, sensation, emotion, thought or behavior.22

The British Psychological Society (BPS)23 definition is:

The term “hypnosis” denotes an interaction between one person, the “hypnotist,” and another person or people, the “subjects.” In this interaction the hypnotist attempts to influence the subjects’ perceptions, feelings, thinking and behaviour by asking them to concentrate on ideas and images that may evoke the intended effects. The verbal communications that the hypnotist uses to achieve these effects are termed “suggestions.” Suggestions differ from everyday kinds of instructions in that they imply that a “successful” response is experienced by the subject as having a quality of involuntariness or effortlessness. Subjects may learn to go through the hypnotic procedures on their own, and this is termed “self-hypnosis.”

A hypnotic subject is often said to be in a “trance,” defined by Oakley24 as “a particular frame of mind characterised by focused attention, dis-attention to extraneous stimuli, and absorption in some activity, image, thought or feeling.” People can and do enter trance spontaneously every day, for example, when lost in thought, daydreaming, or absorbed in a book or listening to music, driving for long distances and not recalling the route taken, or being absorbed in meditation/relaxation procedures. Often in these examples, there will be a feeling of time distortion in that the passage of time is underestimated. We “dip” into these natural trances without being aware that it is going to happen. It is only after we have experienced these trances that we are aware of them.

With hypnosis, however, the subject knows that he or she is going to experience trance before it happens. Hypnotic procedures formalize the process of trance, intensify it, and allow it then to be a useful experience during which suggestions and therapeutic techniques can be utilized. Every experience of trance will differ, however: For many, being in trance may feel similar to the stage just before falling asleep, or when first awakening in the morning. An individual is conscious at these times but the brain is operating at a “lower frequency.” When talking with patients, I often say that in some ways a hypnotic trance can be compared with being absorbed in a good book or film: “You become fully absorbed and if the storyline and suggestions are acceptable to your way of thinking, morals and belief system, they may change the way you think about certain things.” Trance “depth” will fluctuate throughout the hypnotic experience, getting “deeper” and “lighter” at times.

Requirements for hypnosis–some brief notes

Rapport and trust are essential for hypnosis to be effective (see Kane and Olness,7 p. 530). If there is strong rapport and trust between hypnotist and patient, the intervention is far more likely to be successful.

Context and motivation are also essential (see Spiegel and Spiegel25). A patient must have motivation in order to overcome his or her problem. Lack of motivation is one of the reasons why some smokers fail to quit, even when they have had hypnosis. I use this example to reassure patients who have concerns over “control,” as it highlights that actually, the patients themselves maintain control of their actions and beliefs, allowing them freedom of will.

Expectation is also very important. “Many studies have shown that people respond they way they expect to respond and that changing those expectations changes the way they respond.”26

It is worth noting that “hypnotizability” or “hypnotic suggestibility” is thought to have little importance on the efficacy of a hypnotic intervention (except for pain management/analgesia).20 Most people are hypnotizable to some degree, but everyone differs in his or her responsiveness to hypnosis. There is some evidence which suggests that a person’s “hypnotizability” is a fixed trait,14 but other research suggests that a person can be “trained” to become more responsive to hypnosis.27 If a person has been hypnotized before with success, this may be a positive indication that future hypnotic intervention also has potential to be successful. On the other hand, a previous failed experience with hypnosis may warn the clinician that there may be difficulties with, or perhaps issues to be resolved prior to, any hypnotic intervention.

Several hypnotizability scales exist that quantity hypnotizability.20,28,29 Formal scales can be interesting, but are seldom used in clinical practice, as they can be time-consuming. Also, care also has to be taken to avoid decreasing a patient’s expectations when employing such scales should a “low” score be recorded. It is thought that 30% of people will be able to experience a light trance, 50% a medium trance, and 20% a deep trance.

Belief, context, and need are also important factors in all hypnotic intervention. Ewin and Eimer30 describe how hypnosis in emergency situations relies more on these factors rather than “hypnotizability” per se (see also Gow31).

Contraindications

Each hypnosis case should be individually assessed. It is prudent for a practitioner considering hypnosis to ask patients if they have, or have ever been diagnosed with, a mood disorder or mental illness, are depressed, are under the care of a psychiatrist or specialist, are currently having suicidal thoughts or have ever had them. Screening questionnaires for anxiety and depression are useful tools when assessing patients for hypnosis—for example, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.32 Extra care has to be taken if a subject has a history of mental illness, and appropriate referral should be considered. In some cases, hypnosis should be avoided. It would be wise for a dentist to consult with patients’ physicians prior to embarking on hypnotic intervention. Dental practitioners using hypnosis should be aware that their use of hypnosis should be limited to dentistry. It is often appropriate to refer to a doctor or psychologist in cases where there are medical or psychological issues that would be inappropriate for a dentist to treat. Hypnosis is an adjunct to treatment or therapy and as such a dentist should only treat cases where there is a specific dental issue. It is often worth considering asking a patient if they have been hypnotized before, and if so, with what results.

Myths and misconceptions dispelled

There are several common misconceptions and myths about hypnosis that it is important to dispel.29 The information below refutes a few common myths and misconceptions.

Amnesia: Usually, patients will have full recollection, unless the hypnotist has chosen to elicit amnesia, and it has been deemed beneficial to block specific memories.

Control: During hypnosis, subjects are aware and in control. It is for this reason that people who deep down wish to continue smoking, for example, would find hypnosis ineffective in making them stop.

Beliefs: Subjects always keep their core morals and beliefs while hypnotized.

Confidentiality: Often, it is unnecessary for the hypnotist to know the exact details of the problem, so long as the subject is aware of them and the significance they may play to their treatment. Due to the confidential nature of the patient–hypnotist relationship, however, many people are surprised that they are happy to discuss issues that they may have never discussed before with anyone.

Stuck in trance: If tired, a patient may fall asleep; however, no one has ever been “stuck” indefinitely in trance. Occasionally, some patients will take a little longer than others to “come out” of trance. Someone who is hypnotized would return to full awareness naturally after a period of time even if unprompted.

Unlocking lost memories: Hypnosis can help to enhance memories, but once a memory is lost, it is lost forever. Care has to be taken not to elicit “false memories”, whereby a person believes an event he or she has recalled while in trance to be true, when in fact it is either wholly or partly falsely constructed.

Movement in trance: It is important to know that it is OK to move during hypnosis. If someone has an itch, it may cause more distraction avoiding moving and scratching it. Long distance runners often experience trance while running. Patients are also able to easily talk while in trance.

Therapy: Hypnosis is never the therapy itself. Hypnosis is an adjunct to treatment or therapy. The hypnotist should be qualified in treating the specific condition that they are using hypnosis to treat.

Lay hypnosis: In the last century, valuable research has led to the rise in respectability for the use of clinical hypnosis, but there are currently few laws that control the practice of hypnosis. A quick look through the internet or the yellow/white pages highlights the large number of “lay” hypnotists, who may have seemingly impressive credentials. It is firmly held by most medical/dental/psychological hypnosis societies, however, that hypnosis should be only used by a practitioner who is qualified to be working in the specific field of its application.

Stage hypnosis: It is the view of many that hypnosis should never be used as a form of entertainment. Although hypnosis is very safe when practiced responsibly, there may be concerns regarding the safety and well-being of participants in some “stage hypnosis” shows.

Every clinician’s technique and approach to hypnosis will vary to suit their personal style and the individual with whom they are working. Some clinicians prefer, or some cases lend themselves to a more direct approach, while an indirect approach may be indicated at other times. To understand the mechanics of hypnosis and what may be involved in a session, an understanding of certain techniques is helpful. Formal hypnosis sessions usually include use of the following techniques.

Anchoring

“Anchoring” refers to the ability we all have to link or “anchor” an emotion, memory, etc. to a sight, sound, taste, feeling or smell. People set up their own “anchors” frequently—and often have anchors that were set up decades before being reactivated. Some anchors are negative (e.g., the sound of the dentist’s drill, the sight of the white coat, the smell of the dentist’s surgery). Other anchors are positive, for example, the noise at a football or soccer match, the smell of home baking, hugging a close friend or family member, etc.

A positive anchor should be set up before using hypnosis. The patient can then access positive emotions at any time in the future using a signal to themselves from themselves that other people would be totally unaware of. The positive anchor is reinforced during trance. Having a positive anchor set up before induction of hypnosis has the additional benefit that should the patient have an abreaction, the clinician has a technique that can reverse this and allow the patient to feel in a more positive frame of mind. An abreaction is when a patient responds unexpectedly during trance, releasing suppressed emotions and becomes upset. Most abreactions occur when the patient spontaneously regresses to a traumatic, unpleasant or upsetting memory. Although these are unusual, it is important that clinicians set up a positive anchor in order that they can lessen or reverse the negative response. Patients can often become emotionally aroused while working through the problem they have sought to resolve. This is controlled and expected in most cases, and can be part of the therapeutic process. An abreaction differs from this as it is unexpected and spontaneous.

There are several types of “self-anchors” that can be taught to patients; a simple example is, once a positive state is being experienced/remembered by the patients, to ask them to touch their thumb and either middle or index finger on their non-dominant hand. The patient is informed that “this is a private signal to yourself, from yourself and can be used at any time to bring back these positive feelings.” The patient is instructed to strengthen this anchor by using it any time he or she has very positive experiences. This is very important as these instances are often more powerful anchors than the ones simply set by recalling previous positive memories and emotions.

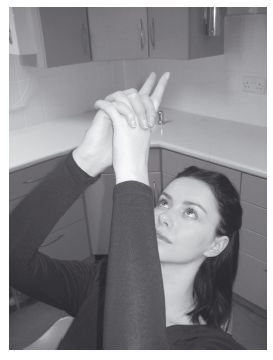

Anchoring a positive state (Figure 6.1)

(1) Decide on a positive state you would like to be in (e.g., happy, confident, etc.)

(2) Recall a specific occasion in the past when you have been in that state.

(3) Recall it as vividly as you can remember all you could see, hear, smell, feel at that time.

(4) Once you are experiencing that positive state, set an anchor to these feelings—for example, squeeze the tip of your thumb together with your middle or index finger on your “nondominant” hand.

(5) Strengthen this anchor by setting it again any time in the future when you experience positive states. The more positive the experience, the more powerful the anchor will become.

(6) Now you can re-access this state whenever it would benefit you by “firing” the anchor.

Figure 6.1 Anchoring. Courtesy of The Berkeley Clinic, Glasgow, UK.

Induction

The hypnotic induction is the start of the formal process of hypnosis and allows the patient to enter a hypnotic trance. There are many induction techniques and the one selected should be one with which the clinician is confident and that is suitable for the patient.

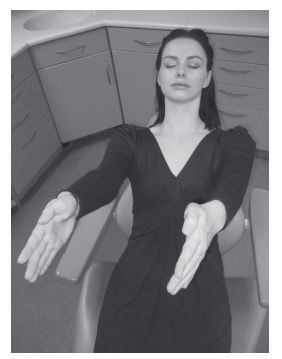

Induction technique example: Hand clasp induction technique (adapted from original technique taught by David Cheek; Figure 6.2)

Clasp your hands together but keep the index fingers straight and separated by two or three centimeters.

Stare at the space between the fingers. As you stare, you will become aware of the fingers wanting to move together. Perhaps you have already noticed that the room is becoming more and more blurry as you focus between the fingers. As the fingers move together, you will become aware of your eyes feeling more strained. You can allow your eyes to close, and your hands to drop comfortably to their lap when the tips of the index fingers finally meet. Just allow the fingers all the time they want. Sometimes they will move together quickly, sometimes it takes a few seconds.

Figure 6.2 Hand clasp induction technique. Courtesy of The Berkeley Clinic, Glasgow, UK.

(Due to the position of the hands and tendons, the subject would actively have to resist the natural tendency for the fingers to move together. If the fingers do not move together, it may be that the subject has some reservations about being hypnotized.)

Deepening

A deepening technique is essentially any technique which “deepens” the patient’s trance following the induction procedure. There are many techniques that can be employed as deepening techniques. Usually, it is unnecessary for the patient to be in deep trance for most dental hypnosis applications (perhaps with the exception of acute pain control). There are many techniques that aid relaxation and ultimately facilitate deepening. Progressive muscular relaxation was first described by Jacobson.33 He understood that as muscular tension accompanies anxiety, anxiety can be reduced by learning how to relax muscular tension.

The “laughing place” (a variation of what is known as the safe place, special place, relaxing place, happy place, etc.) is a very effective deepening technique34 (p. 55), and is also very useful in most hypnotherapy sessions. A deepening technique favored by the author is the “hands together” deepening technique, as it also ratifies to the patient that they are experiencing trance. The hands together technique is also an example of what is called an ideomotor response. This is a phenomenon whereby the subject experiences physical movement that is unconscious, and therefore appears to occur independent of conscious direction. It is worthy of note that the hypnotist should always watch the patient’s breathing and deliver their suggestions on the outward breath.

Deepening technique example: “Hands coming together” (Figure 6.3)

The subject’s arms should be outstretched directly in front at shoulder width apart, with palms facing each other.

“I would like you to be aware that there is a natural tendency for your arms and hands to move together … . By thinking about this tendency … you can make it stronger and stronger and your hands will move closer and closer together …. Imagine that your hands are charged like two magnets … with the opposite poles facing each other … . And as you breathe in … and out … I wonder if you notice now, or will notice in a few moments … that your hands are beginning to draw a little closer together … like two magnets … closer and closer … . I don’t know if the right hand will be more attracted to the left or if the left will be more attracted to the right … and, I don’t know whether your hands will come together quickly or whether it will take a little longer … closer and closer … like two magnets … closer and closer … and like two magnets … as your hands get closer and closer together…so the attraction between them will grow stronger … closer and closer…closer still … until they will soon meet … I don’t know which part of them will meet first … but as they meet … you will become twice as relaxed as you were before … and so now as they are about to meet you can look forward to your hands drifting back down to a comfortable position … I don’t know whether they will feel more relaxed by your side or on your lap … closer and closer just like two magnets until they finally touch … (repeat relevant sections until the hands meet) … and as your hands touch together … and you feel so deeply relaxed … allow them to find that comfortable position … that’s good … now notice that all normal sensations and feelings have returned to your hands … you may like to verify this by moving or wiggling your fingers … feeling even more relaxed now than before … deeply, deeply relaxed and comfortable.

Figure 6.3 Hands together deepening technique. Courtesy of The Berkeley Clinic, Glasgow, UK.

Ego strengthening

Ego-strengthening techniques are intended to improve the self-esteem, self-belief, and inner strength, etc., of the patient. Many believe that ego strengthening is among the most important techniques and suggestions that a therapist can use during a hypnotic intervention. Ego strengthening has been said to “stand as the bedrock upon which other hypnotic techniques are structured.”35

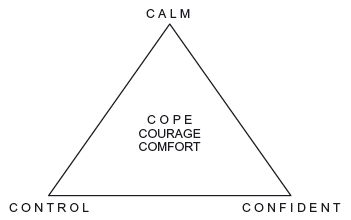

Ego strengthening example: “Calm, control and confident” script (adapted from original technique described by Craig et al.36; Figure 6.4)

This script assumes the patient is able to create mental images (i.e., is a “visualizer”), and should be tailored as required. The technique should be adapted to the patient’s individual “Special Place,” the following example uses a sandy beach. The triangle and words may be drawn on any object, with any object. Additional words may be included in the center of the triangle which are appropriate for the patient and their needs—for example, COPE, COURAGE, COMFORT, etc.

Picture yourself on your sandy beach. You can see the sand below your feet. … When you can see this, just let me know by allowing your right index finger to move … (Prompt until finger moves. If it fails to move even following further prompting continue with: “if you are unable to see this, relax because we are just going to consider some words.”)

Very good. Now imagine that with a stick or a shell or perhaps just your finger you can draw a triangle in the sand … —that’s right, very good. Now around the triangle at its corners you will write some words…starting at the top…with the word … CALM. See the letters as you spell out the word C … A … L … M … . (Spell out the letters, pacing each letter with an outward breath) Notice how the sand feels as you write the word CALM with the stick. Just allow yourself this feeling of CALM … enjoy this feeling … from now on feeling calmer and calmer every day … every day feeling calmer and calmer…more and more calm … more optimistic … these feelings of calmness growing and increasing … calmer and calmer … more composed … more at peace … calm … C … A … L … M. …

Figure 6.4 Calm control confident ego strengthening technique.

Now choose one of the remaining corners of the triangle … or allow it to choose you … the corner by which you would like to write the second/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses