Pediatric Dentistry

Learning Outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the student will be able to achieve the following objectives:

• Pronounce, define, and spell the Key Terms.

• Describe the appearance and setting of a pediatric dental office.

• List the stages of childhood from birth through adolescence.

• Describe why children and adults with special needs are treated in a pediatric practice.

• Describe what is involved in the diagnosis and treatment planning of a pediatric patient.

• Discuss the importance of preventive dentistry in pediatrics.

Performance Outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the student will be able to achieve competency standards in the following skills:

Electronic Resources

![]() Additional information related to content in Chapter 57 can be found on the companion Evolve Web site.

Additional information related to content in Chapter 57 can be found on the companion Evolve Web site.

• Interactive Dental Office Patient Case Studies: Margaret Brown, Bret Goodman, and Raul Ortega, Jr.

• Procedure Sequencing Exercises

• WebLinks

Key Terms

Analogy (uh-NAL-uh-jee) Comparison of similarities between things that are otherwise not alike.

Athetosis (ATH-e-toe-sis) Type of involuntary movement of the body, face, and extremities.

Autonomy (aw-TON-uh-mee) Childhood process of becoming independent.

Avulsed (uh-VULST) Torn away or dislodged by force.

Cerebral palsy (suh-REE-brul PAWL-zee) Neural disorder of motor function caused by brain damage.

Chronologic age (KRON-uh-loj-ik) Actual age (months, years) of pediatric patients.

Contour (KON-toor) To shape or conform an object.

Down syndrome Chromosomal defect that results in abnormal physical characteristics and mental impairment; also called trisomy 21.

Emotional age Measure of the level of emotional maturity of pediatric patients.

Extrusion (ek-STROO-zhun) Displacement of a tooth from its socket as a result of injury.

Frankl (FRANG-kul) scale Scale designed to evaluate patient behavior.

Intrusion (in-TROO-zhun) Displacement of a tooth into its socket as a result of injury.

Luxation (luk-SAY-shun) Dislocation.

Mental age Measure of the level of intellectual capacity and development of pediatric patients.

Mental retardation Disorder in which an individual’s intelligence is underdeveloped.

Neural (NUR-uhl) Referring to the brain, nervous system, and nerve pathways.

Open bay Concept of open design used in pediatric dental practices.

Papoose (pa-POOS) board Type of restraining device that holds a pediatric patient’s hands, arms, and legs still.

Pediatric (pee-dee-AT-rik) dentistry Dental specialty concerned with neonatal through adolescent patients, as well as patients with special needs in these age groups.

Postnatal (post-NAY-tul) After birth.

Prenatal Before birth.

Pulpotomy (pul-POT-uh-mee) Removal of the coronal portion of a vital pulp from a tooth.

Spasticity (spas-TIS-i-tee) Exaggerated movement of the arms and legs.

T-band Type of matrix band used for primary teeth.

Pediatric dentistry is the specialized area of dentistry that focuses on providing oral healthcare according to the needs of infants, children, adolescents, and of individuals with special healthcare needs. Emphasis of the pediatric dental practice is placed on prevention, early detection, diagnosis, and treatment. Although many of the procedures completed for children are similar to those for adult patients, pediatric patients require special adaptations and techniques in the way dentistry is provided (Fig. 57-1).

The Pediatric Dentist

A pediatric dentist will continue his or her education for an additional 2 to 3 years after dental school in an accredited pediatric program based in a dental school setting. The program of study and hands-on experience prepares the specialist to meet the needs of infants, children, adolescents, and persons with special healthcare needs.

The Pediatric Dental Assistant

As a dental assistant in a pediatric setting, you must have the compassion and patience to enjoy working with children, adolescents, and patients with special needs. Pediatric dentistry provides a clinical practice (“hands-on”) environment where you will have an active role in the patient’s dental care. Many pediatric dental offices employ the certified dental assistant to perform preventive procedures that are legal in that state. If coronal polishing, application of sealants, and taking of preliminary impressions are legal functions, these expanded functions would become responsibilities of the credentialed dental assistant.

The Pediatric Dental Office

The pediatric dental office displays cheerfulness and a pleasant environment with a nonthreatening decor. Many offices will have a “theme” in the overall decor, such as a rain forest, outer space, or even a popular movie character (Fig. 57-2).

When entering a pediatric dental practice, you will notice that the treatment areas are not confining or structured. Many practices are designed with the open bay concept, in which several dental chairs are arranged in one large area. The advantage of this design is that it provides reassurance by allowing pediatric patients to see other children who are receiving care. This can be psychologically effective because children are often hesitant to express fear or to misbehave in the presence of other children.

If an isolated area is required for patient care, most practices will use a “quiet room.” This room is separate from the open area and can be used for children whose behavior may upset other children.

A variety of reading materials, such as magazines and educational brochures, should be available for both the pediatric patient and the parent. Some offices install computer and video equipment with programs intended for patient education and entertainment.

Many pediatric offices are less “medical looking” with regard to how dental personnel dress. It is common for “scrubs” to be worn in bright coordinating colors or designs (Fig. 57-3). Name tags worn by the staff may even resemble a tooth, with the assistant’s name inscribed.

The Pediatric Patient

Children constitute an important and special portion of the dental population. As with adults, children have individual likes and dislikes, as well as fears and complex personalities. The pediatric patient must be treated with the same respect for dignity and individuality as is provided to an adult. The child must be understood in terms of his or her chronologic, mental, and emotional ages:

• Chronologic age is the child’s actual age in terms of years and months.

• Mental age refers to the child’s level of intellectual capacity and development.

• Emotional age describes the child’s level of emotional maturity.

These ages are not necessarily the same in each child. For instance, a child at the chronologic age of 6 may have a mental age of 8 (i.e., mentally, the child is comprehending information at the level of the average 8-year-old) and an emotional age of 4 (i.e., emotionally, he or she is reacting at the level of the average 4-year-old).

According to a well-known psychiatrist, Erik Erikson, the socialization process consists of stages. These stages were formulated to understand the social and emotional development of children and teenagers. A guideline (norm) for the average child’s development can be used as a simple index to the child’s anticipated behavior level at a certain age. A child who differs widely from these norms may be physically or emotionally challenged. It is important to remember that some children may be under the stress of a dental appointment and could temporarily regress to a more immature level of behavior.

Erikson’s Stages of Development

Learning Basic Trust

Chronologically, this is the period of infancy through the first year of life. The child, well handled, nurtured, and loved, develops trust and security and a basic optimism. If handled badly, the infant will become insecure and mistrustful.

Learning Autonomy

During this period, children learn to sit, stand, walk, and run. Vocally, they progress from babbling to using simple sentences. Socially, they learn to identify familiar faces and alternate through periods of being friendly and being fearful of strangers.

Around the age of 2 years old, children begin to have basic fears associated with separation from the parent and a related fear of strangers. These “toddlers” are too young to be expected to cooperate with dental treatment. It is easier for the parent to be with the child during the initial examination. If further treatment is required, the child most likely will be premedicated.

Play Age

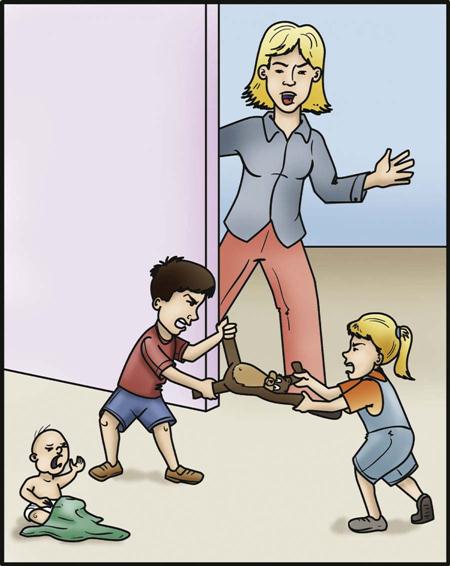

A child 3 to 5 years of age has two primary and somewhat conflicting needs (Fig. 57-4). First, the child has gone through a process of developing autonomy and initiative. Second, the child requires control and structure in his or her environment. Children are able to follow simple instructions, and they welcome having an active role in the treatment experience. The child’s role is to help by following directions and “sitting still,” “keeping your hands by your side,” and “opening your mouth wide.” By allowing the child to have choices, the dental team shows regard for the child’s need for autonomy and initiative.

School Age

The child age 6 to 11 is in a period of socialization, which involves learning to “get along” with people, learning the rules and regulations of society, and learning to accept these social requirements. Through their experiences with others, these children have learned to overcome fears of objects and situations that were once quite frightening to them. They have learned that situations usually are less threatening than they had imagined, and that generally they need not be afraid.

Adolescence

From age 12 to 20, young people acquire self-certainty (Fig. 57-5). They experiment with different roles. Clear sexual identity is established. The adolescent will seek leadership (someone to inspire them) and will gradually develop a set of ideals.

Behavior Management

The initial examination is important for both the child and the dental team. Remember that this often is the first dental experience for the child. The rapport developed during the initial examination can establish an attitude toward dental health that will last for a child’s lifetime.

Many dentists will follow a behavior scale early in the treatment of a pediatric patient. The child’s behavior then can be evaluated and followed through the child’s experience in the practice. Dr. Spencer Frankl developed one of the most widely used systems, the Frankl scale, to measure a pediatric patient’s behavior (Table 57-1).

TABLE 57-1

Frankl Scale for Pediatric Dental Patient Behavior

| Rating | Definition | Patient behavior |

| 1 | Definitely negative | Refusal of treatment; crying forcefully; fearful; other evidence of extreme negativism |

| 2 | Negative | Reluctance to accept treatment; uncooperative; some evidence of negative attitude but not pronounced, that is, no sudden withdrawal |

| 3 | Positive | Acceptance of treatment; cautious at times; willingness to comply, at times with reservation, but follows directions |

| 4 | Definitely positive | Good rapport with dentist; interested in dental procedures; laughing and enjoying the situation |

Courtesy Dr. Spencer Frankl.

Guidelines for Child Behavior

The development of trust between the parent/child and the dentist serves as the basis for a productive, effective means of providing dental healthcare. Dental procedures can be accomplished for patients of all ages if the dental team practices the following procedural guidelines:

The Challenging Patient

Treating an anxious, fearful, or uncooperative child can be challenging for the dentist, assistant, parents, and especially for the child. In some situations, a child will remain uncooperative despite the fact that the dental team has used every possible approach to provide a positive dental experience. Occasionally, a child’s behavior during treatment requires a more assertive management style to be used to protect him or her from possible injury. Voice control (speaking calmly but firmly) will usually prevent the need for additional steps.

In certain cases, some form of restraint may be required for the patient’s protection. A restraint can be physical or pharmacologic, to help keep a patient’s movement or activity to a minimum. If the dentist knows that restraint will be needed, premedication can be prescribed to calm and ease the patient before treatment. Mild sedation, such as nitrous oxide/oxygen or a sedative, may benefit an anxious child. If a child is especially fearful or requires extensive treatment, other sedative techniques or general anesthesia may be recommended (see Chapter 37).

Physical restraint can be as simple as the dentist or assistant holding a child’s hands during treatment. By holding the child’s hands, you can prevent possible injury to the child, the dentist, and yourself, if, for instance, the child were to quickly reach for the syringe during an injection or for the dentist’s arm while using the handpiece.

For young toddlers and preschool-age children, a parent may be asked to help keep the child calm and under control. A problem with this scenario is that if a parent is anxious or nervous about the child’s care, bringing him or her back into the clinical setting may actually impair the situation and create an even more nervous environment.

Additional steps for restraining a child can be taken with the use of a papoose board. This device gently “hugs” or wraps around the child’s arms, legs, and middle section during a procedure. The papoose board uses Velcro straps that fasten over the child and restrains the movement of the child’s hands, arms, and legs (Fig. 57-6). This device is excellent for the younger child who has been sedated, or for the patient with special needs who may have limited control of his or her movement.

When the dentist takes steps in using pharmacologic or physical restraint with a child, the parents must be made aware and must provide consent. An immediate and documented explanation should be given to parents as to why such actions are to be taken. The child should also be informed appropriately.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses