Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

Learning Outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the student will be able to achieve the following objectives:

• Pronounce, define, and spell the Key Terms.

• Describe the specialty of oral and maxillofacial surgery.

• Discuss the role of an oral surgery assistant.

• Discuss the importance of the chain of asepsis during a surgical procedure.

• Identify specialized instruments used for basic surgical procedures.

• Describe surgical procedures typically performed in a general practice.

• Describe postoperative care given to a patient after a surgical procedure.

Performance Outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the student will be able to achieve competency standards in the following skills:

• Assist in a simple extraction.

• Assist in a multiple extraction procedure with alveoplasty.

Electronic Resources

![]() Additional information related to content in Chapter 56 can be found on the companion Evolve Web site.

Additional information related to content in Chapter 56 can be found on the companion Evolve Web site.

Key Terms

Alveolitis (al-vee-oh-LI-tis) Pain and inflammation resulting from exposed bone associated with the disturbance of a blood clot after extraction of a tooth.

Alveoplasty (al-VEE-uh-plas-tee) The surgical shaping and smoothing of the margins of the tooth socket after extraction of a tooth, generally in preparation for placement of a prosthesis.

Bone file Surgical instrument used to smooth rough edges of bone structure.

Chisel Surgical instrument used for cutting or severing a tooth and bone structure.

Curette (kyoo-RET) Surgical instrument used to remove tissue from a tooth socket.

Donning Act of placing on an item, such as gloves; dressing.

Elevator Surgical instrument used to reflect and retract the periodontal ligament and periosteum.

Excisional biopsy (ek-SIZH-uh-nul BYE-op-see) Surgical procedure in which tissue is cut from a suspected oral lesion.

Exfoliative (eks-FOE-lee-uh-tiv) biopsy Diagnostic procedure in which cells are scraped from a suspected oral lesion for analysis.

Forceps (FOR-seps) Surgical instrument used to grasp and hold onto teeth for their removal.

Hard tissue impaction (im-PAK-shun) Oral condition in which a tooth is partially to fully covered by bone and gingival tissue.

Hemostat (HEE-moe-stat) Surgical instrument used to hold or grasp items.

Impacted tooth Tooth that has not erupted.

Incisional (in-SIZH-uh-nul) biopsy Section of suspect oral lesion that is removed for evaluation.

Luxate (LUK-sayt) To dislocate, as a tooth from its socket.

Mallet Hammer-like instrument used with a chisel to section teeth or bone.

Needle holder Surgical instrument used to hold the suture needle.

Oral and maxillofacial (MAK-sil-oe-fay-shul) surgeon (OMFS) Dentist who has specialized in surgeries of the head and neck region.

Oral and maxillofacial (MAK-sil-oe-fay-shul) surgery Dental surgical specialty that diagnoses and treats conditions of the mouth, face, jaws, and associated areas.

Outpatient Patient seen and treated by a physician, then sent home for recovery.

Retractor (ree-TRAK-tur) Surgical instrument used to hold soft tissue away from the surgical site.

Rongeur (raw-ZHUR, RON-gore) Surgical instrument used to cut and trim the alveolar bone.

Root tip picks Surgical instrument used for the removal of root tips or fragments from the surgical site.

Scalpel (SKAL-pul) Surgical knife.

Soft tissue impaction Oral condition in which a tooth is partially to fully covered by gingival tissue.

The specialty of oral and maxillofacial surgery is involved in the diagnosis and surgical treatment of diseases, injuries, and defects affecting the hard and soft tissues of the head and neck region.

Indications for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

• Extraction of decayed teeth that cannot be restored

• Surgical removal of impacted teeth

• Extraction of nonvital teeth

• Preprosthesis surgery to smooth and contour the alveolar ridge

• Removal of teeth for orthodontic treatment

• Biopsy

• Treatment of fractures of the mandible or maxilla

• Surgery to alter the size or shape of the facial bones

• Surgery of the temporomandibular joint

The Oral Surgeon

The oral and maxillofacial surgeon (OMFS), also referred to as an oral surgeon, is a dentist who has received 4 to 6 additional years of postgraduate training in a hospital-based residency. The oral surgeon finishes a core surgical-medical year before program completion, with an emphasis on surgical techniques, anesthesiology, and oral medicine. The surgeon must pass a national standardized examination of the American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery as a requirement for practice. Most surgeons today have obtained their medical license as well.

The general dentist receives training in simple oral surgery procedures and can complete these in the private practice setting. For specific areas of the mouth and more complicated procedures, however, many dentists will refer their patient to a specialist.

The Surgical Assistant

The surgical assistant is one of the most important members of the surgical team. Surgical procedures are invasive and in-depth, requiring the surgical assistant to have advanced knowledge and skill in (1) patient assessment and monitoring, (2) use of specialized instruments, (3) surgical asepsis, (4) surgical procedures, and (5) pain control techniques.

After completion of a general dental-assisting program, dental assistants can further their education and training in a specialized program for surgical dental assistants, or through additional on-the-job training. Dental assistants who assist the oral surgeon in a surgical setting are often required to obtain certification in advanced cardiac life support, and the use of additional monitoring procedures.

The Surgical Setting

The surgical team completes procedures in two types of settings: the private dental office and the hospital or outpatient surgical suite.

Private Practice

An oral surgeon’s private practice medicodental-surgical office consists of treatment areas similar to those in a general practice. In addition to treatment areas, the office will have surgical suites that resembles operating rooms, but on a much smaller scale. Specific items used only for surgical procedures, such as monitoring equipment, pain control units, and mobile trays, replace items seen in a general practice.

The patient who is receiving surgical care from an OMFS in an office setting is considered as having minor surgery and is being seen as an outpatient. The patient will be advised to arrive a short time before the scheduled surgery and receive surgical treatment, recover, and be escorted home to complete the recovery phase.

Operating Room

The operating room of a hospital or ambulatory setting is quite different from a private practice (Fig. 56-1). To acquire permission from a hospital to use its clinical facility, the oral surgeon must submit an application for privileges to practice at a particular institution. The hospital will then grant privileges to the oral surgeon on the basis of his or her training, competency, and experience.

The environment is spacious enough to accommodate the (1) operating table, (2) anesthesiology equipment, (3) mobile surgical trays, holding instruments, and supplies, (4) overhead lighting, (5) monitoring equipment, and (6) standing room for the surgeon, surgical assistant, roving assistant, and anesthesiologist.

Specialized Instruments and Accessories

It is critical for the surgical assistant to have a working knowledge and understanding of surgical instruments. Such knowledge prepares the surgical staff for the sterilization and preparation of a surgical setup and ordering of the instruments and enables staff to be ready to assist.

Surgical instruments are designed to separate the tooth from the socket, retract surrounding tissue, loosen and elevate the tooth within the socket, or extract the tooth from the socket. The instruments discussed in this chapter are the oral surgical instruments that are most commonly used. All surgical instruments are classified as critical instruments and must be sterilized after each use.

Elevators

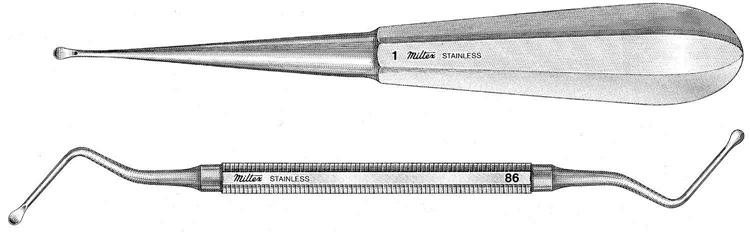

Periosteal elevators are available in many designs but are used to perform the same basic function (Fig. 56-2): to reflect (separate) and retract the periosteum from the surface of the bone. Before a surgical forcep is placed around the tooth, the dentist uses a periosteal elevator to detach the gingival tissues from around the cervix (neck) of the tooth.

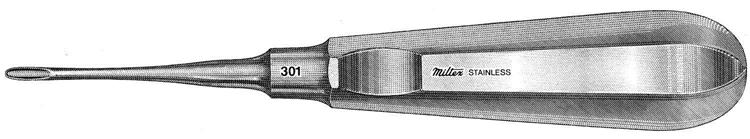

Straight elevators are used to apply leverage against the tooth to loosen it from the periodontal ligament and ease the extraction (Fig. 56-3). Additional uses include removal of residual root fragments and removal of teeth that have been sectioned with a surgical handpiece and bur.

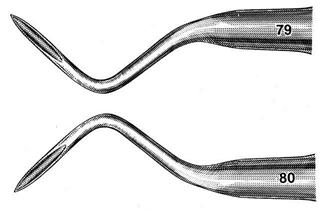

Root tip picks are instruments used for the removal of root tips or fragments that may break away from the tooth during the extraction procedure (Fig. 56-4).

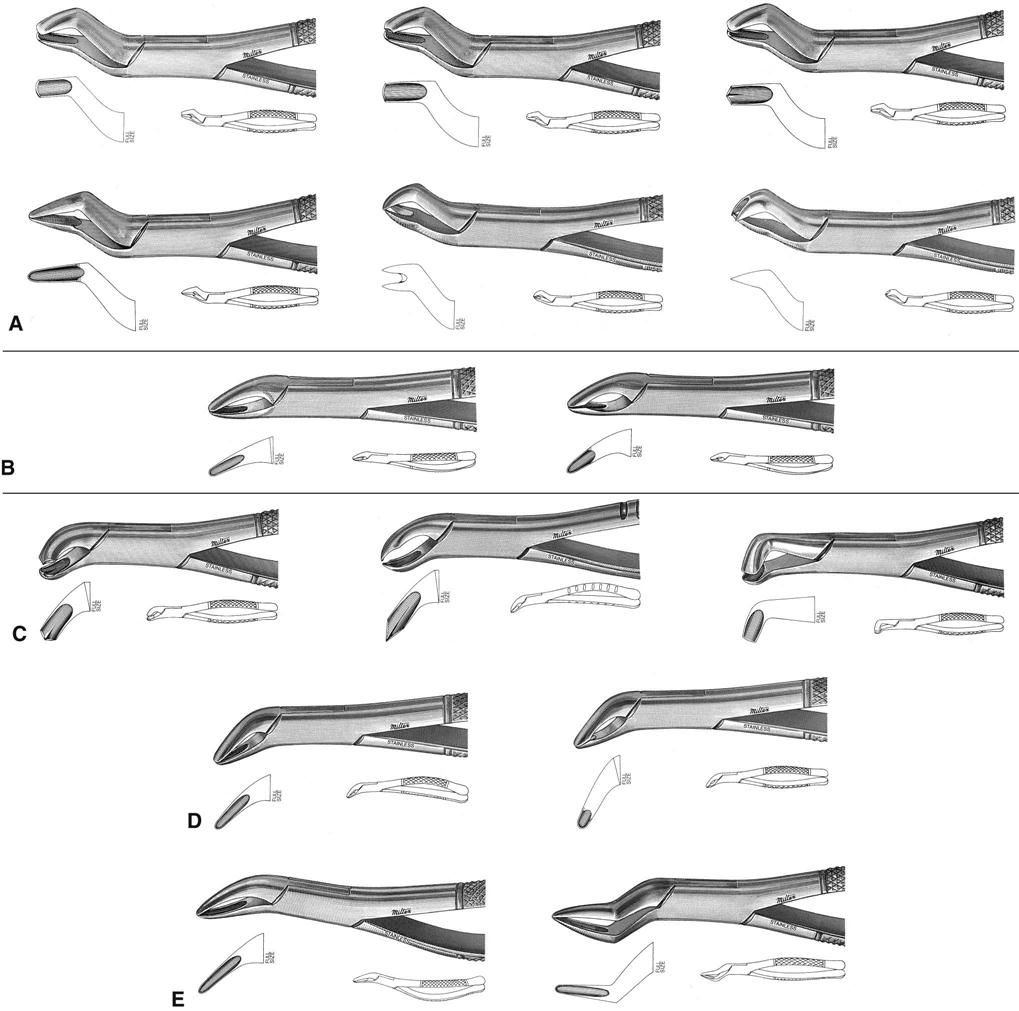

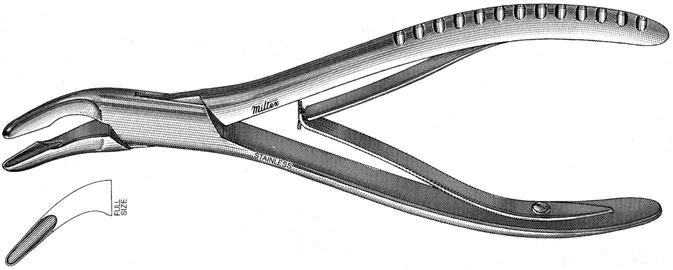

Forceps

Extraction forceps are available in many different shapes and designs and are able to accommodate the oral surgeon’s needs in grasping teeth with different crown shapes, root configurations, and locations in the mouth. The goal is to remove the tooth in one piece with the crown and root intact.

The beaks of forceps are shaped to grasp the crown of the tooth firmly at or below the cervical line. The inner surface of the beaks may be plain (smooth finished) or serrated (rough finished) to provide additional grasping power of the tooth being extracted. The handles can be horizontal (side by side) or vertical.

Forceps are used to remove teeth from the alveolus after they have been slightly loosened in the sockets by the application of elevators. The handles, which are held firmly in a palm grasp, provide the dentist with the leverage necessary to luxate and remove the tooth.

Universal forceps are designed to allow the surgeon to use the same instrument for the left and right sides of the same arch, as well as for a specific tooth. Figure 56-5 covers forceps commonly used for specific areas of the mouth.

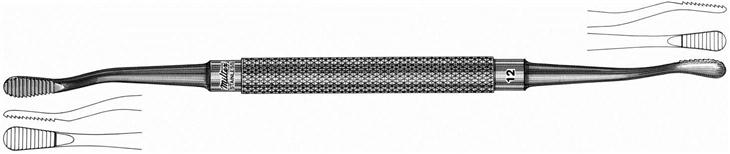

Surgical Curette

The surgical curette resembles a large spoon excavator. It is a double-ended, scoop-shaped instrument with sharp edges that allow for a scraping motion. Curettes are used following the extraction to scrape the interior of the socket to remove diseased tissue or abscesses. Curettes come in varying sizes, and the shanks may be straight or angled to reach different areas of the mouth (Fig. 56-6).

Rongeur

The rongeur is similar in its size to the forceps, and the design resembles that of fingernail clippers. The rongeur has a spring between the handles and the blades with sharp cutting edges. The blades of the rongeur may be end cutting or side cutting, depending on the design (Fig. 56-7).

The rongeur is used to trim alveolar bone. It is widely used after multiple extractions to eliminate sharp projections and to shape the edentulous ridge. The beaks of the rongeur must be kept clean during the procedure. As necessary, the dentist holds the instrument toward the assistant with the beaks open. The assistant then carefully removes the debris by wiping the beaks with a sterile gauze sponge.

Bone File

The bone file is used with a push-pull motion to smooth the surface of the bone after the rongeur has removed most of the undesirable bone. Bone files also can be used to smooth rough margins of the alveolus after an extraction. The working ends of bone files are very rough and are available in a variety of shapes and sizes (Fig. 56-8).

Scalpel

The scalpel is a surgical knife used to make a precise incision into soft tissue with the least amount of trauma to the tissue. The size and shape of the blade selected depend on the procedure that is being performed and on the dentist’s preference (Fig. 56-9). Disposable scalpels have plastic handles with metal blades and are supplied in sterile sealed packages. These instruments are designed to be used once and then discarded into the “sharps” container. Care must be taken to avoid injury while the blades are attached and removed. The use of a mechanical scalpel blade remover helps avoid injury during the removal of scalpel blades.

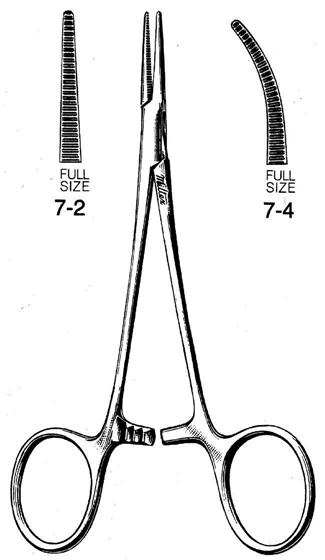

Hemostat

Hemostats are multipurpose instruments that are used to grasp and hold things. During oral surgery, a hemostat is used to grasp soft tissue, bone, and tooth fragments that have been removed during the procedure. A hemostat has grooves in its beak that are used for grasping and holding. The handles have a mechanical lock that holds an object or tissue securely within the beaks (Fig. 56-10). These instruments are available in a variety of sizes, with straight and curved beaks and with handles of different lengths.

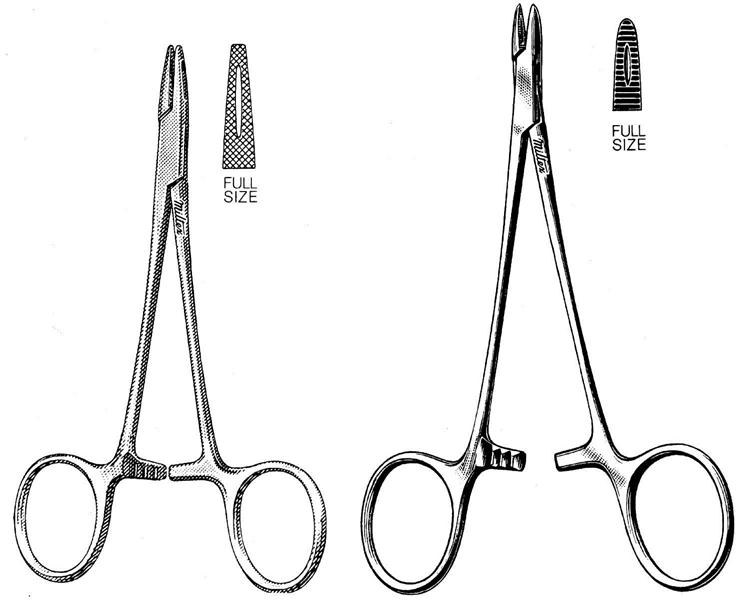

Needle Holder

The needle holder looks and operates similarly to a hemostat. The beaks are straight with cross-pattern serrations on the surface, allowing the surgeon to grasp a suture needle firmly (Fig. 56-11). The handles are held in place by a ratchet action that holds an object until the dentist releases it. This handle design allows the dentist to tie the suture material by using the needle holder without snagging it in the joint of the instrument.

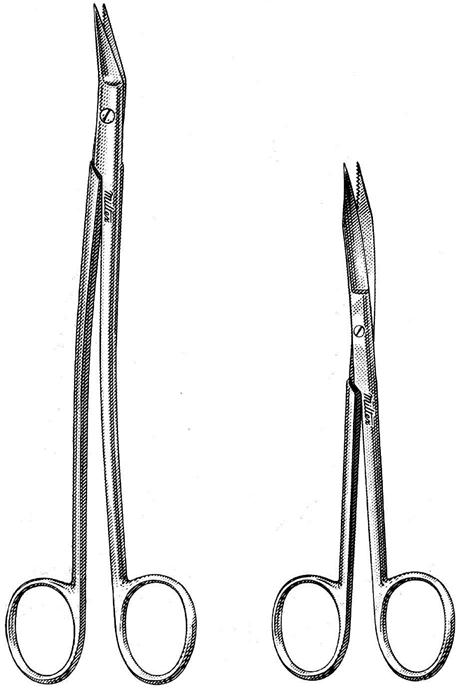

Surgical and Suture Scissors

Surgical scissors are available with straight or curved blades that have smooth or serrated cutting edges (Fig. 56-12). The handles range in length from approximately  to

to  inches. These delicate scissors are used to trim soft tissue. Surgical scissors should never be used for nonsurgical tasks that would dull the cutting surfaces.

inches. These delicate scissors are used to trim soft tissue. Surgical scissors should never be used for nonsurgical tasks that would dull the cutting surfaces.

Suture scissors are designed to cut only suture material. Although similar in des/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses