Chapter 4

Selecting Surgery Equipment for the Dental Hygienist

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to highlight the specific surgery requirements for a dental hygienist to manage periodontal disease efficiently and effectively.

Outcome

Having read this chapter, clinicians will have a source of reference for the selection of instruments and equipment recommended for the dental hygienist.

The Decision-Making Process

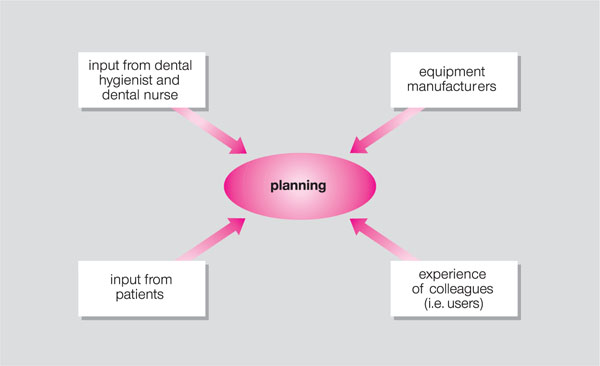

Before deciding on the requirements for a surgery, it is important to gather and collate information from various sources (Fig 4-1).

Fig 4-1 Collation of resources for surgery planning.

The Surgery Layout and Equipment

It is not the remit of this book to include details of general dental equipment common to all surgeries, but rather to focus on the specific requirements of dental hygienists. Some of these may be similar to those of a dentist’s surgery but other requirements differ.

The hygienist requires as much operative space as the dentist and the equipment and layout should give a similar impression to the patient to when they enter the dentist’s surgery. Patients with periodontal disease are likely to visit the hygienist more often than the dentist. It is therefore important to create an environment of comfort and relaxation compatible with universal cross-infection control procedures. If the hygienist has “second-hand” equipment in a small room, it is worth reflecting on the image this may portray to the patient (Fig 4-2).

Fig 4-2 “Welcome to the broom cupboard.”

A key priority in surgery planning is ergonomics. Dental clinicians suffer from occupational musculoskeletal problems and hygienists are no exception. According to MacDonald and colleagues (1988), approximately 29% of hygienists suffer from carpal tunnel syndrome and other associated upper body neuropathies. There are several risk factors contributing to the occupational component of this syndrome (Box 4-1). The utilisation of the working space, the equipment, and choice of the instruments are essential considerations in the preventive strategies for a condition which is painful and debilitating or may, in some cases, lead to forced early retirement.

Box 4-1

Major Risk Factors in Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Operator position

Force needed to grasp instrument handles

Mechanical stress from power leads and cords

Vibration from ultrasonics

Temperature of surgery and hand washing water

Posture

Dental hygienists work from the 12 o’clock to the 8 o’clock chair positions. For a right-handed operator, treatment of the lower anterior, lower right posterior, upper anterior and upper right posterior sextants is frequently conducted with the patient semi-supine and the hygienist facing the patient (Fig 4-3). This positioning enables the operator to work by direct vision and to keep the lower back upright and the wrist in the neutral position. Wrist flexion increases compression in the carpal tunnel by 200%. In order to achieve the optimal position there must be sufficient space for the operator’s chair to be manoeuvred between the dental chair and the fixed cabinetry.

Fig 4-3 Positioning of both patient and operator is important in maintaining good posture.

Force

Handpieces attached to curled cords tend to exert greater force on the wrist. This design should preferably be avoided, but if they are already installed then the hygienist can support the cord to minimise the force (Fig 4-4).

Fig 4-4 Support of the hand piece cord reduces force on the wrist.

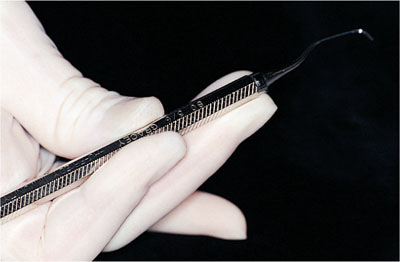

Similarly, with hand instruments, grasping and forceful exertion during scaling may lead to symptoms. This can be avoided by using ergonomically designed, silicone covered lightweight instruments. Thin hexagonal shaped handles require more force and pushing to secure them in the fingers (Figs 4-5 and 4-6). This also contributes to mechanical stress. Vibration damage to the small blood vessels occurs at 20–80 Hz. Whilst the ultrasonic scaler is an essential part of the hygienist’s equipment, it is useful to plan appointments so that its use is not continuous.

Fig 4-5 Hexagonal shaped handles are pinched to ensure a sound grip.

Fig 4-6 An ergonomically designed silicone handle is held lightly.

Temperature

Low temperature constricts the blood flow and accentuates the symptoms of nerve-end compression. The ambient temperature should be around 25°C.

Radiographic Equipment

Dental hygienists who have undertaken the IR(ME)R2000 regulations training are permitted to take radiographs prescribed by the dentist. If x-ray equipment is installed in their surgery, or at a designated x-ray workstation, this will enable dental hygienists optimally to utilise their skills. However, if the equipment is solely in the dentist’s surgery they are less likely to be called upon to take radiographs because of the economic use of surgery time.

This will lead to the hygienist becoming de-skilled and loosing confidence in taking radiographs.

Equipment for Patient Education

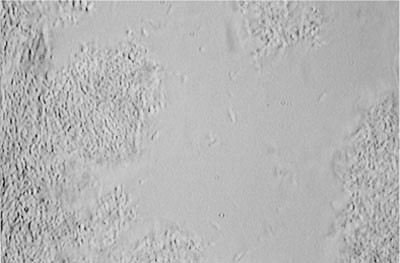

As discussed in Chapter 3, the dental hygienist has a vital role to play in informing the patient about the nature of the disease in their mouth. The education may be personalised by the use of intraoral cameras and phase-contrast microscopy which allows the hygienist to demonstrate plaque organisms magnified × 1000 (Fig 4-7). This is an excellent motivating tool as comparative samples can be taken at subsequent appointments to review plaque control.

Fig 4-7 Phase-contrast microscopy to demonstrate plaque morphotypes (× 1000).

Equipment for Scaling and Root Debridement

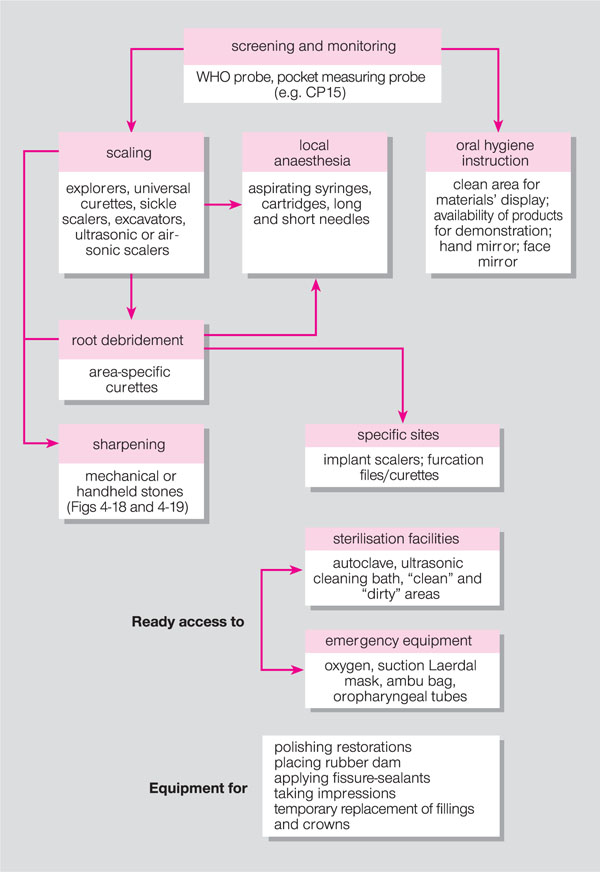

The reader is referred to Fig 4-8 for the equipment and instruments recommended for safe, effective clinical practice.

Fig 4-8 Specific equipment for the dental hygienist’s surgery.

Screening

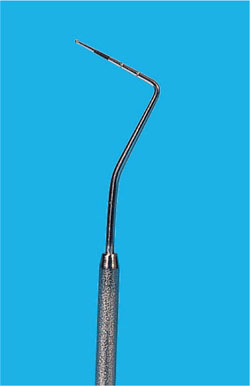

The WHO probe (Fig 4-9) is essential for Basic Periodontal Examinaton screening. Its ball end is also suitable for establishing bleeding on probing.

Fig 4-9 WHO probe.

Monitoring

/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses