Chapter 38 Maxillary Sinus Anatomy, Pathology, and Graft Surgery

Maxillary posterior partial or complete edentulism is one of the most common conditions in dentistry.1 Thirty million people in the United States, or 17.5% of the adult population, are missing all of their maxillary teeth. In addition, 20% to 30% of the adult partially edentulous population older than 45 years is missing maxillary posterior teeth in one quadrant, and 15% of this age group is missing the maxillary dentition in both posterior regions. In other words, approximately 40% of adult patients are missing at least some maxillary posterior teeth. This chapter addresses the treatment concepts specific to the maxillary posterior partial or complete edentulous regions.

The maxillary posterior edentulous region presents many unique and challenging conditions in implant dentistry. Most noteworthy surgical methods include sinus grafts to increase available bone height, onlay grafts to increase bone width, and modified surgical approaches to insert implants in areas with poorer bone density.2 Grafting of the maxillary sinus to overcome the problem of reduced vertical available bone has become a very popular and predictable procedure over the last decades. After the initial introduction by Tatum in the mid 1970s and the initial publication of Boyne and James in 1980, many studies have been published about sinus grafting with positive results.3–38 In 1983, Misch2 observed the most predictable intraoral region to grow bone height is on the maxillary sinus floor, once the sinus mucosa has been elevated. This statement still holds true today.

ANATOMICAL CONSIDERATIONS OF THE POSTERIOR MAXILLA

The maxilla has a thinner cortical plate on the facial compared with any region of the mandible. In addition, the trabecular bone in the posterior maxilla is finer than other dentate regions. The loss of maxillary posterior teeth results in an initial decrease in bone width at the expense of the labial bony plate. The width of the posterior maxilla decreases at a more rapid rate than in any other region of the jaws.39 The resorption phenomenon is accelerated by the loss of vascularization of the alveolar bone and the existing fine trabecular bone type. However, because the initial residual ridge is so wide in the posterior maxilla, even with a 60% decrease in the width of the ridge, adequate-diameter root form implants usually can be placed. However, the ridge progressively shifts toward the palate until the ridge is resorbed into a medially positioned narrower bone volume.40 The posterior maxilla continues to progressively remodel toward the midline as the bone resorption process continues. This results in the buccal cusp of the final restoration often being cantilevered facially to satisfy esthetic requirements at the expense of biomechanics in the moderate to severe atrophic ridges.41

DENTAL CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR IMPLANT TREATMENT OF THE POSTERIOR MAXILLA

Abnormal intraoral conditions may compromise the final outcome of sinus-grafting procedures and/or the survival rates of dental implants placed in the grafted sinuses. These contraindications are similar to those reported for standard implant treatment of edentulous patients and may be summarized as follows:

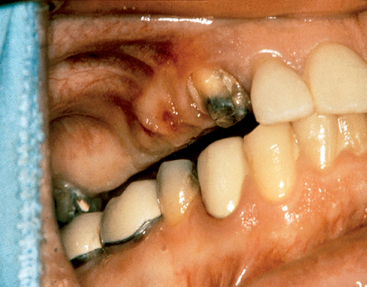

Decreased Crown Height Space

The crown height space (CHS) should be evaluated before implant placement. Once the occlusal plane is properly restored or modified, the CHS should be greater than 8 mm (Figure 38-1). If less space is available for prosthodontic reconstruction, then a gingivectomy is first considered because it is not uncommon for excess tissue thickness to be present in this region. However, if tissue reduction cannot correct the CHS problem, then osteoplasty and/or vertical osteotomy of the maxillary posterior alveolar process are indicated to improve the vertical ridge orientation before implant surgery.

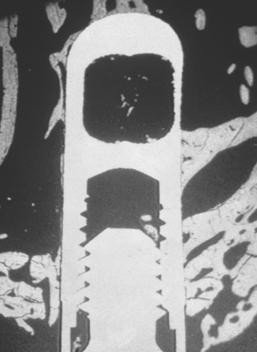

Poor Bone Density

In general, the bone quality is poorest in the posterior maxilla compared with any other intraoral region.42 A literature review of clinical studies from 1981 to 2001 reveals the poorest bone density may decrease implant loading survival by an average of 16%, and it has been reported as low as 40%.43 The cause of these failures is related to several factors. Bone strength is directly related to its density, and the poor-density bone of this region is often five to 10 times weaker compared with bone found in the anterior mandible.44 Bone densities directly influence the bone-implant contact percent (BIC), which accounts for the force transmission to the bone. The BIC is least in D4 bone, and the stress patterns in this bone migrate farther toward the apex of the implant (Figure 38-2). As a result, bone loss is more pronounced and occurs also along the implant body, rather than only crestally as in other denser bone conditions. D4 bone also exhibits the greatest biomechanical elastic modulus difference when compared with titanium under load.44 As such, strategic choices to increase BIC are suggested.

Implant Size

The ideal length of the implant is directly related to the implant width, the design, the amount of the forces, and the bone density. Because implant success after loading is reduced in implants shorter than 10 mm, it is logical to treatment plan longer implants in the region. In general, 4-mm threaded root form implants should be at least 12 mm in length when the bone density is poor. This usually provides adequate BIC to dissipate the loads applied to the prosthesis. Implants longer than 16 mm are not necessary, even in the softest bone type, because the stress transfer is not dissipated beyond this length. Therefore the implant most often should be 12 to 16 mm long in this region of the mouth. Sinus grafting is usually required before or in conjunction with implant placement to gain adequate bone height for implants of adequate length in this region. The poor bone density requires implants of a larger size, including length. The implant length requirement is greater because the transmission of stress is expressed farther down the implant length.

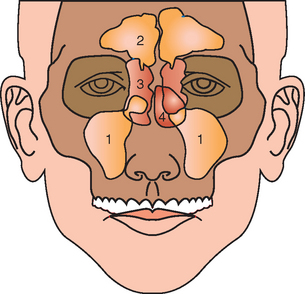

MAXILLARY SINUS

The anatomy of the maxillary sinuses was first illustrated and described by Leonardo da Vinci in 1489 and later documented by the English anatomist Nathaniel Highmore in 1651.45 The maxillary sinus (or antrum of Highmore) lies within the body of the maxillary bone and is the largest of the paranasal sinuses, as well as the first to develop (Figure 38-3).

Maxillary Sinus Development

A primary pneumatization of the maxillary sinus occurs at about 3 months of fetal development by an out-pouching of the nasal mucosa within the ethmoid infundibulum. At this time the maxillary sinus is a bud situated at the infralateral surface of the ethmoid infundibulum between the upper and middle meatus.46 Prenatally, a secondary pneumatization occurs. At birth, the sinuses are filled with fluid and the maxillary sinus is still an oblong groove on the mesial side of the maxilla, just above the germ of the first deciduous molar.47

Postnatally and until the child is 3 months of age, the growth of the maxillary sinus is closely related to the pressure exerted by the eye on the orbit floor, the tension of the superficial musculature on the maxilla, and the forming dentition. As the skull matures, these three elements influence its three-dimensional (3D) development. At 5 months, the sinus appears as a triangular area medial to the infraorbital foramen.48

During the child’s first year, the maxillary sinus expands laterally underneath the infraorbital canal, which is protected by a thin bony ridge. The antrum grows apically and progressively replaces the space formerly occupied by the developing dentition. The growth in height is best reflected by the relative position of the sinus floor. At 12 years of age, pneumatization extends to the plane of the lateral orbital wall, and the sinus floor is level with the floor of the nose. The main development of the antrum occurs as the permanent dentition erupts and pneumatization extends throughout the body of the maxilla and the maxillary process of the zygomatic bone. Extension into the alveolar process lowers the floor of the sinus about 5 mm (Figure 38-4). Anteroposteriorly, the sinus expansion corresponds to the growth of the midface and is completed only with the eruption of the third permanent molars when the young person is about 16 to 18 years of age.46–48

In the adult, the sinus appears as a pyramid of five thin, bony walls. The base of this pyramid faces the lateral nasal wall and often measures 33 × 33 mm; its apex extends approximately 23 mm toward the zygomatic bone.49,50 The dentate adult maxillary sinus has an average volume of 15 mL, although the range is 9.5 to 20 mL.51 The floor of the maxillary sinus cavity is reinforced by bony or membranous septa joining obliquely or transversely from the medial and/or lateral walls with buttresslike webs. They may be genetic or develop as a result of stress transfer within the bone over the roots of teeth. These have the appearance of reinforcement webs in a wooden boat and rarely divide the antrum into separate compartments. These elements are present from the canine to the molar region, and Misch41 has observed they tend to disappear in the maxilla of the long-term edentulous patient when stresses to the bone are reduced. Karmody et al.52 found that the most common oblique septum is located in the superior anterior corner of the sinus or infraorbital recess (which may expand anteriorly to the nasolacrimal duct). The medial wall is juxtaposed with the middle and inferior meatus of the nose.

Although the adult maxillary sinus maintains its overall size while the teeth are present, a rather rapid expansion phenomenon of the maxillary sinus occurs with the loss of posterior teeth. In fact, even with the loss of a single molar, the sinus expands between the adjacent tooth roots. In the edentulous maxilla, the antrum expands in both inferior and lateral dimensions and may even invade the canine eminence region and proceed to the lateral piriform rim of the nose. This results in a lack of available bone in the posterior maxilla and a greatly decreased height from both the sinus expansion and the crestal resorption. Frequently, less than 10 mm remains between the alveolar ridge crest and the floor of the maxillary sinus in the edentulous posterior maxilla. This limited dimension is compounded by the problem of bone of reduced quality and the resultant medial posterior position of the ridge after resorption of bone width. As a result, compromises in the long-term prognosis of many endosteal implant systems are reported.43

Maxillary Sinus Anatomy

Six bony walls that contain many structures of concern during sinus graft surgery surround the maxillary sinus.45,53 Knowledge of these structures is crucial for both preoperative assessment and postsurgical complications.

Anterior Wall

The anterior wall of the maxillary sinus consists of thin, compact bone extending from the orbital rim to just above the apex of the cuspid. With the loss of the canine, the anterior wall of the atrum may approximate the crest of the residual ridge. Within the anterior wall and approximately 6 to 7 mm below the orbital rim, with anatomic variants as far as 14 mm from the orbital rim, is the infraorbital foramen (Figure 38-5). The infraorbial nerve runs along the roof of the sinus and exits through the foramen. The infraorbital blood vessels and nerves lie directly on the superior wall of the interior and within the sinus mucosa. Tenderness to pressure over the infraorbital foramen or redness of the overlying skin may indicate inflammation of the sinus membrane from infection or trauma. The anterior wall of the maxillary sinus may serve as surgical access during Caldwell-Luc procedures to treat a preexisting or post–sinus graft, pathologic condition.

Superior Wall

The superior wall of the maxillary sinus is shared with the thin orbital floor (Figure 38-6). The orbital floor slants inferiorly in a mediolateral direction and is convex into the sinus cavity. A bony ridge is usually present in this wall that houses the infraorbital canal containing the infraorbital nerve and associated blood vessels. Dehiscence of the bony chamber may be present, resulting in direct contact between the infraorbital structures and the sinus mucosa. Ocular symptoms may result from infections or tumors in the superior aspects of the sinus region and may include proptosis (bulging of the eye) and diplopia (double vision). When these problems occur, the patient is closely supervised and a medical consult is advised to decrease the risk of severe complications that may result from the spread of infection in a superior direction. Superior spreading infections may lead to a brain abscess and death. As a result, when these symptoms appear, aggressive therapy to decrease the spread of infection is indicated. Overpacking the maxillary sinus with bone graft material during a sinus graft may result in pressure against the superior wall if a sinus infection develops.

Medial Wall

The medial wall of the antrum coincides with the lateral wall of the nasal cavity and is the most complex of the various walls of the sinus (see Figure 38-6). On the nasal aspect, the lower section of the medial wall corresponds to the lower meatus and floor of the nasal fossa; the upper aspect corresponds to the middle meatus. The medial wall is vertical and smooth on the antral side. Located in the superior aspect of the medial wall is the maxillary or primary ostium. This structure is the main opening through which the maxillary sinus drains its secretions via the ethmoid infundibulum through the hiatus semilunaris into the middle meatus of the nasal cavity. The infundibulum is approximately 5 to 10 mm long and drains via ciliary action in a superior and medial direction. This opening corresponds to the initial site of embryonic evagination from the nasal chamber. The ostium diameter averages 2.4 mm in health; however, pathologic conditions may alter the size to vary from 1 to 17 mm. Smaller, accessory or secondary ostia may be present that are usually located in the middle meatus posterior to the main ostium. These additional ostia are usually the result of chronic sinus inflammation and mucous membrane breakdown. They are present in approximately 30% of skulls, range from a fraction of a millimeter to 0.5 cm, and are commonly found within the membranous fontanelles of the lateral nasal wall.54 Fontanelles are usually classified either as anterior fontanelles (AFs) or posterior fontanelles (PFs) and termed by their relation to the uncinate process. These weak areas in the sinus wall are sometimes used to create additional openings into the sinus for treatment of chronic sinus infections. Primary and secondary ostia may, on occasion, combine and form a large ostium within the infundibulum.

Lateral Wall

The lateral wall of the maxillary sinus forms the posterior maxilla and the zygomatic process (see Figure 38-6). This wall varies greatly in thickness from several millimeters in a dentate patient to less than 1 mm in an edentulous patient. The lateral wall houses an endosseous anastamosis of the infraorbital and posterior superior alveolar artery. The Tatum lateral-wall approach sinus graft procedure uses this area for entrance into the maxillary sinus (Figure 38-7).

Inferior Wall

The inferior wall or floor of the maxillary sinus is in close relationship with the apices of the maxillary molars and premolars (see Figure 38-6). The teeth usually are separated by the sinus mucosa by a thin layer of bone; however, on occasion, teeth may perforate the floor of the sinus and be in direct contact with the sinus lining. Studies have shown that the first molar has the most common dehiscent tooth root, occurring approximately 2.2% of the time. In dentate patients, the floor is approximately at the level of the nasal floor. In edentulous posterior maxillae, the sinus floor is often 1 cm below the level of the nasal floor. Complete or incomplete bony septa may exist on the floor in a vertical or horizontal plane. Almost 30% of the dentate maxillae have septa, with three fourths appearing in the premolar region.55,56 Complete septa separating the sinus into compartments are very rare, occurring in only 1.0% to 2.5% of maxillary sinuses.

Maxillary Sinus: Vascular Supply and Innervation

The formation of the endosseous and extraosseous anastomoses in the maxillary sinus is termed the double arterial arcade. The extraosseous anastomosis is less common (present in 44% of the population) and is found near the periosteum of the lateral wall. The extraosseous anastomosis is superior to the endosseous unit, which is approximately 15 to 20 mm from the dentate alveolar crest. In addition to the double arterial arcade, a blood supply from the sphenopalatine artery supplies the central and medial parts of the sinus membrane. This artery is also a branch of the maxillary artery and enters the maxillary sinus on the medial aspect via the maxillary ostium57(Box 38-1).

Box 38-1 Arterial Supply to Posterior Maxilla (Double Arterial Arcade)

In an edentulous maxilla with posterior vertical bone loss, the endosseous anastamosis may be 5 to 10 mm from the edentulous ridge. The endosseous artery was able to be observed on computed tomography (CT) scans in approximately one half of the patients requiring a sinus graft.58 In a long-term edentulous patient with a thin lateral wall, the artery may be atrophied and almost nonexistent. On rare occasions, this anatomical structure may be a concern for arterial bleeding complications during lateral-approach sinus elevation surgery.

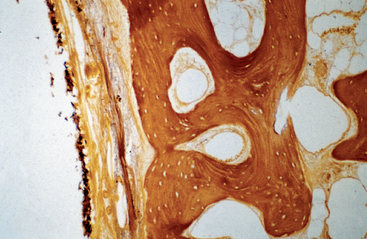

The entire circulatory system in the maxillary sinus is a vital part of the healing and regeneration of bone after a sinus graft. Different factors can alter the vascularization in this area. With increasing age, the number and size of blood vessels in the maxilla decrease. As bone resorption increases, the cortical bone becomes thin, resulting in less vascularization. As the lateral wall becomes thinner, the blood supply to the lateral wall and lateral aspect of the bone graft comes primarily from the periosteum, resulting in a compromised vascularization to the region (Figure 38-8). After surgery the arterial supply in the lateral outer wall (in spite of being severed during the procedure) may help vascularize the sinus graft, because the anastomoses may vascularize the graft from both the posterior region and anterior region.

The nerve supply to the maxillary sinus is via numerous branches of the second division of the trigeminal nerve, including the posterior alveolar nerves, anterior palatine, and infraorbital nerves. The infraorbital nerve is of concern in sinus elevation surgery because of its anatomical position. This nerve enters the orbit via the inferior orbital fissure and continues anteriorly; the nerve lies in a groove in the orbital floor (which is also the maxillary sinus superior wall) before exiting the infraorbital foramen. Anatomical variants have been reported to include a dehiscence and malpositioned infraorbital foramen, along with the nerve transversing the lumen of the maxillary sinus rather than coursing through the bone within the sinus ceiling (orbital floor).

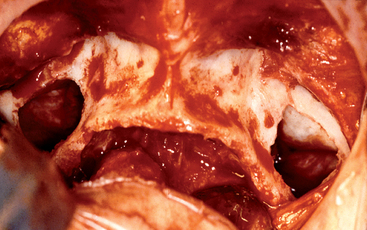

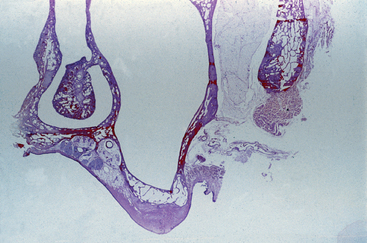

Maxillary Sinus Mucosa: Microscopic Anatomy

Although the sinus mucosa has been called a mucoperiosteum, Sharawy and Misch59 suggested that the periosteal portion of this membrane is not similar to the periosteum covering the cortical plates of the maxillary or mandibular residual ridges of the jaws and should not be considered a mucoperiosteum (Figure 38-9). The very minimal and usual absence of osteoblasts in this tissue and, instead, the presence of osteoclasts, may account for the enlargement of the antrum after tooth loss. The maxillary sinus membrane also exhibits few elastic fibers attached to the bone,59 which simplifies elevation of this tissue from the bone. The thickness of the sinus mucosa varies, but is generally 0.3 to 0.8 mm.60 In smokers, it varies from very thin and almost nonexistent to very thick, with a squamous type of epithelium.

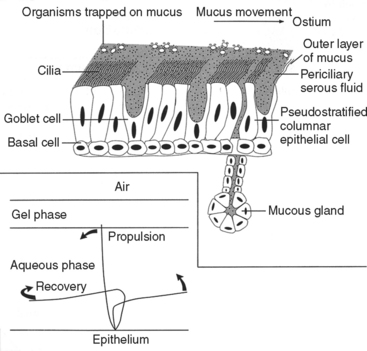

Maxillary Sinus Mucous Clearance

The mucus of the maxillary sinuses is produced from serous and goblet cells, which produce 1 L of mucus each day in healthy conditions. The cilia in the maxillary sinus beat toward the ostium. A blanket of mucus is propelled toward the ostium by the beating motion of the ciliated lining cells. The mucous material of the sinus in health has two layers: (1) a top mucoid layer and (2) a bottom serous layer (Figure 38-10). The top layer is sticky and collects bacteria and other debris, whereas the serous layer is thin and acts as a lubricant. The cilia of the columnar epithelium beat toward the ostium at 15 cycles per minute, with a stiff stroke through the serous layer, reaching into the mucoid layer. The cilia recover with a limp reverse stroke within the serous layer. This mechanism slowly propels the mucoid layer toward the ostium at a rate of 9 mm per minute and into the middle meatus of the nose.60

Various elements may decrease the number of cilia and slow their beating efficiency. Viral infections, pollution, allergic reactions, and certain medications may affect the cilia in this way.61–63 Genetic disorders (e.g., dyskinetic cilia syndrome) and factors such as long-standing dehydration, anticholinergic medications and antihistamines, cigarette smoke, and chemical toxins also can affect ciliary action. Certain pathogens (Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) associated with sinusitis have been shown to release a compound that slows and disorganizes ciliary beating along with affecting mucous transport. Various medications have also been shown to affect ciliary action. Decongestant medications may alter the various layers of the sinus membranes, thus interrupting normal ciliary activity. On the other hand, long-term antibiotic medications have been shown to have a significant increase in ciliary beat frequency.61

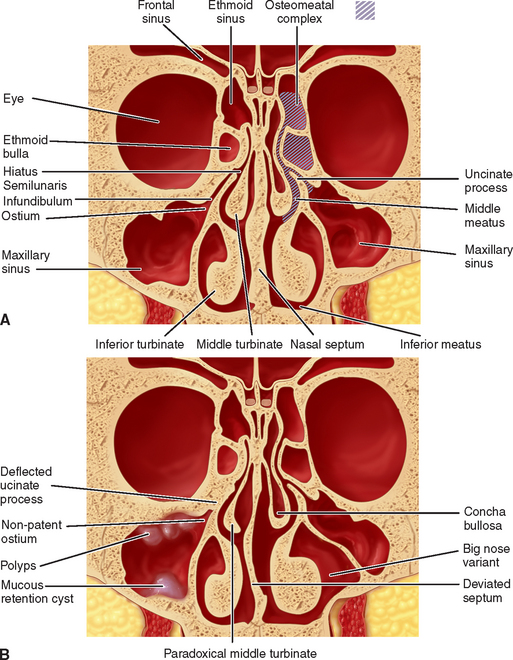

In a healthy sinus, an adequate system of mucus production, clearance, and drainage is maintained. The key to normal sinus physiologic condition is the proper function of the cilia, which are the main component of the mucociliary transport system. These cilia work to move contaminants toward the natural ostium and then to the nasopharynx. The flow of mucus is toward the ostium, which leads to the infundibulum, through the hiatus semilunaris, into the middle meatus of the nose, and ultimately into the nasopharynx (Figure 38-11). An alteration in the sinus ostium patency or the quality of secretions can lead to disruption in ciliary action resulting in sinusitis. For clearance to be maintained, adequate ventilation is necessary. Ventilation and drainage is dependent on the osteomeatal unit, which is the main sinus opening. Ciliary movements of ciliated epithelial cells dictate clearance of the maxillary sinus.

The maxillary ostium and infundibulum are part of the anterior ethmoid middle meatal complex, the region through which the frontal and maxillary sinuses drain, which is primarily responsible for mucociliary clearance of the sinuses to the nasopharynx.64 As a result, pathogenesis of sinusitis is usually the development of obstruction in one or more areas of this complex.65 Symptomatic sinusitis corresponds to the blockage of the osteomeatal complex that drains the paranasal sinuses. Symptoms of sinusitis may be minimal, even in the presence of extensive radiographic findings, as long as the patency of the ostium is maintained.66

Maxillary Sinus Bacterial Flora

Much debate concerns the bacterial flora of the maxillary sinus. Maxillary sinuses have been considered to be sterile in health; however, bacteria can colonize within them without producing symptoms. In theory, the mechanism by which a sterile environment is maintained includes the mucociliary clearance system, immune system, and the production of nitrous oxide within the sinus cavity. In a study of patients who underwent surgical repositioning of the maxilla, Cook and Haber67 reported that 80% of the patients showed no bacterial growth. The remaining 20% had some bacterial growth but in negligible numbers. All specimens showed some degree of inflammatory cell infiltrate, more acute in the presence of microorganisms. They concluded that the asymptomatic adult maxillary sinus is usually sterile, but a few transient bacteria may exist in a clinically asymptomatic antrum.

However, recent endoscopically normal sinuses were shown to be nonsterile, with 62.3% exhibiting bacterial colonization. The most common bacteria cultured were Streptococcus viridans, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae.68 The culture findings for secretions in acute maxillary sinusitis yielded high numbers of leukocytes, S. pneumoniae, or Streptococcus pyogenes, and Haemophilus influenzae was recovered from the purulent exudates with lower numbers of staphylococci. In fact, the macroscopic appearance of the secretion should not be used to screen samples, because several cases with H. influenzae grew also from nonpurulent samples. Other reports have indicated the bacterial flora of the maxillary sinus consists of nonhemolytic and α-hemolytic streptococci, as well as Neisseria spp. Additional microorganisms identifiable in various quantities belong to the staphylococci, Haemophilus spp., pneumococci, Mycoplasma spp., and Bacteroides spp. This is important to note because the sinus graft procedure often violates the sinus mucosa, and bacteria may contaminate the graft site.

Maxillary Sinus: Clinical Assessment

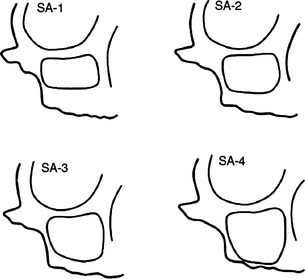

To establish an adequate osseous morphologic condition for the placement of endosteal implants in the resorbed maxillary posterior region, various grafting techniques have been developed to increase bone volume. In 1987, Misch69 developed four different categories for the treatment of the posterior maxilla (termed subantral [SA]), as SA-1 through SA-4 (Figure 38-12). The SA-1 posterior maxilla allows implant placement inferior to the sinus cavity without sinus manipulation, thus not altering the sinus floor or membrane. As such, if the patient has a preexisting maxillary sinus condition or develops a sinus infection after implant placement, then implants are not at risk of becoming contaminated. However, the SA-2 to SA-4 surgical procedures do alter the sinus membrane and sinus floor. With these treatment options, a thorough preoperative evaluation is completed to rule out existing pathologic condition in the maxillary sinus. In this way, the risk of mucus and bacteria contaminating the graft and creating a bacterial smear layer on the implant, which results in impaired bone formation during healing, is reduced. In addition, because of the proximity of the maxillary sinus to numerous vital structures, postoperative complications can be very severe and even life threatening.

Pathologic conditions associated with the paranasal sinuses are common ailments and afflict more than 31 million people each year. Approximately 16 million people will seek medical assistance related to sinusitis; yet sinusitis is one of the most commonly overlooked diseases in clinical practice.70 Potential infection in the region of the sinuses may result in severe complications. Infections in this area have been reported to result in sinusitis, orbital cellulitis, meningitis, osteomyelitis, and cavernous sinus thrombosis. In fact, paranasal sinus infection accounts for approximately 5% to 10% of all brain abscesses reported each year.70

A physical examination of the maxillary sinus evaluates the middle third of the face for the presence of asymmetry, deformity, swelling, erythema, ecchymosis, hematoma, or facial tenderness (Table 38-1). Nasal congestion or obstruction, prevalent nasal discharge, epistaxis (bleeding from the nose), anosmia (the loss of the sense of smell), and/or halitosis (bad breath) are noted.

Table 38-1 Preoperative and Postoperative Physical Examination

| SITE | SIGNS OF INFECTION |

|---|---|

| Inferior wall | Bulge in hard palate, ill-fitting denture, loose teeth, hypesthesia or nonvital teeth, bleeding, palatal erosion, oroantral fistula |

| Medial wall | Nasal obstruction, nasal discharge, epistaxis, cacosmia, visible mass in nostril |

| Anterior wall | Swelling, pain, skin changes |

| Lateral wall | Trismus, bulging mass, exudate from incision line |

| Posterior wall | Midface pain, hypesthesia of one half of face, loss of function of lower cranial nerves |

| Superior wall | Diplopia (double vision), proptosis (eye bulging out), chemosis, pain or hypesthesia, decreased visual acuity |

Maxillary Sinus Radiographic Evaluation

Waters’ Projection Radiographs

The most common medical plain-film radiograph used for the evaluation of the maxillary sinus is the occipitomental projection, also termed the Waters’ projection. This film is taken with the patient’s head tilted upwards approximately 40 degrees, allowing a clear evaluation of the superior, lateral, and medial aspects of the maxillary sinus. Before the advent of CT technology, this projection was used routinely for the evaluation of maxillary sinus disease. The Waters’ projection is often complimented with similar plain films such as the Caldwell (frontal view), lateral view, and submentovertical (base view). However, the posterior teeth and/or alveolar residual bony process frequently obscure the posteroinferior part of the sinus cavity. Because the sinus floor is a critical portion of the sinus for implant treatment, a Waters’ projection radiograph has little use for diagnosis or treatment planning in implant dentistry. It has been reported that 75% of these plain films are inaccurate in evaluating the pathologic condition of the sinuses.71

Panoramic Radiographs

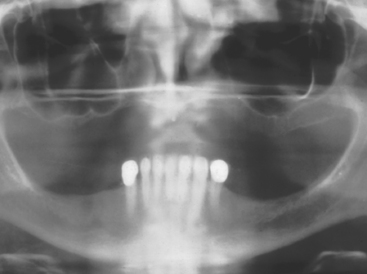

The panoramic radiograph is often used as a preliminary diagnostic radiograph in implant dentistry. This radiograph can provide direct visualization of the anterior, lateral, and inferior regions of the maxillary sinus. It is often sufficient to evaluate the amount of bone present below the maxillary sinus (Figure 38-13).

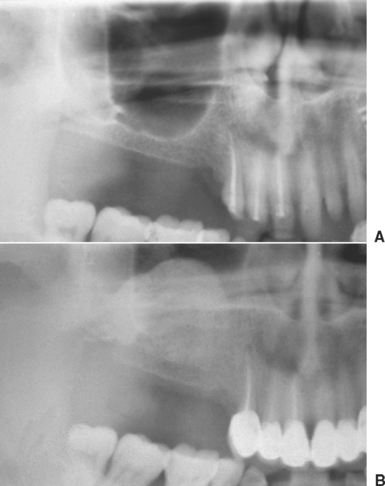

The panoramic radiograph is useful for preliminary evaluation of the posterior maxilla. However, it is not the standard radiograph used to evaluate the maxillary sinus for abnormalities or pathologic conditions. Ghost and overlapping images will often obscure or distort the anatomy of the maxillary sinus. If the patient is positioned upward with respect to the Frankfort horizontal plane, then the hard palate and the shadow of the occipital bone will obscure the sinus. Another common positioning mistake is not placing the tongue in the roof of the mouth. This will result in radiolucency over the maxilla that represents the palatoglossal air space, as well as a radiopaque region from the tongue. This radiopaque region may be misinterpreted as a pathologic condition. The posterior wall of the maxillary sinus is often misinterpreted as the panoramic innominate line. This artifact is a thin, vertical radiopaque line in the posterior one third of the maxillary sinus that corresponds to the superimposition of the zygomatic process of the maxilla and the frontal process of the zygoma. The posterior region behind this innominate line is often more radiopaque and may be misinterpreted as available bone “behind the sinus” for endosteal implants (Figure 38-14).72

The panoramic radiograph may be used as the only radiographic tool in an SA-1 treatment option. Because the sinus and/or floor is not manipulated during the surgery, the condition of the sinus proper is much less relevant to implant insertion. Because the SA-3 or SA-4 sinus graft procedure augments the posterior maxilla, it transforms the region to an SA-1 condition after graft maturity. Therefore after a sinus graft has positively modified the existing bone volume, a panoramic radiograph is often the only radiographic modality used before implant surgery.

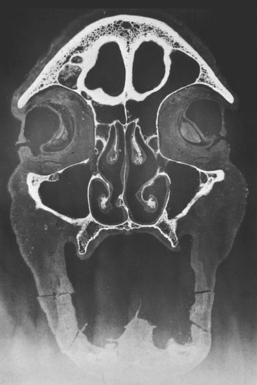

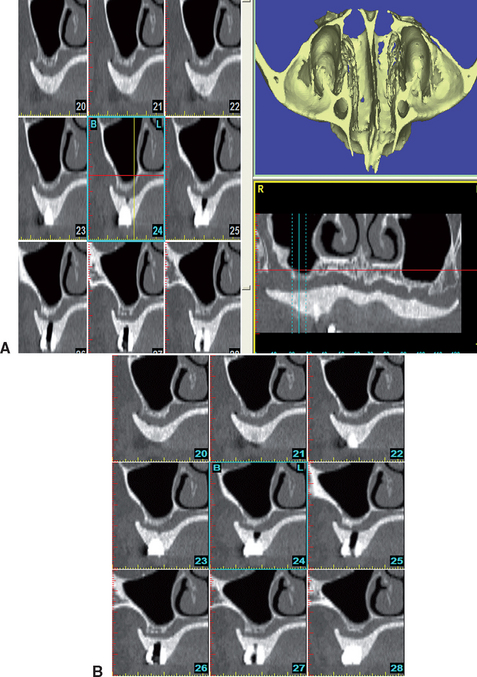

Computerized Tomography

Currently, no radiographic modality provides more information about the paranasal sinuses than CT. This type of radiography provides much more detailed information about the anatomy and pathologic condition of the sinuses compared with plain films. CT is the best option for viewing the surrounding osseous structures and pathologic condition in the maxillary sinuses.65,73,74 With the addition of reformatted images, axial, panoramic, cross-sectional, and 3D images provide comprehensive evaluation of the entire sinus cavity and the existing bone below the antrum. In medical evaluation of the sinus cavity, images are taken in the coronal plane. For dental reformatted images, scans are usually taken in numerous transaxial slices (Figure 38-15).

Maxillary Sinus: Computed Tomography Radiographic Anatomy

Maxillary Sinus: Anatomical Variants

Numerous anatomical variants arise that can predispose a patient to postsurgical complications. When these conditions are noted, a pharmacologic discipline may be altered and/or implants may be placed after the sinus graft has matured, rather than predisposing them to an increased risk by inserting them at the same time as the sinus graft. As stated previously, patency of the ostium is paramount to maintain drainage. Preexisting skeletal and bony abnormalities of the osteomeatal complex may compromise the unit, leading to maxillary sinusitis.

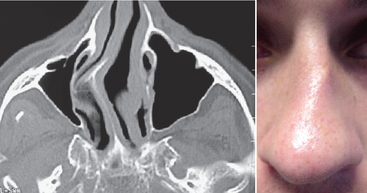

Nasal Septum Deviation

A nasal septum deviation is a very common anatomical variant, occurring in as much as 70% of the population older than 14 years. This bony variant in extremes may cause obstruction of the ostiomeatal unit, which results in inflammation from air turbulence, causing increased mucosal drying and particle deposition. If the deviation is long standing, then atrophy of the middle turbinate may occur, resulting in narrowing of the ostiomeatal complex (Figure 38-16).75

Timmenga et al.76 evaluated 45 patients who received 85 sinus grafts with endoscopy postsurgery. Of the 45 patients, five were found to have sinusitis postsurgery; all five of those patients had a nasal deviation or oversized turbinate. Therefore when these conditions are observed, the implant should not be placed at the same time as the sinus graft, and the recommended preoperative and postoperative pharmacologic protocol is especially warranted.

Middle Turbinate Variants

The middle turbinate plays a significant role in proper drainage of the maxillary sinus. A concha bullosa is a pneumatization within the middle turbinate and may occlude the osteomeatal complex, thus compromising adequate drainage. This variant is seen in approximately 4% to 15% of the population (see Figure 38-11).77 Another variant in this anatomical structure is a paradoxically curved middle turbinate, which presents a concavity toward the septum, thus decreasing the size of the meatus. This also predisposes the patient to sinus disease.

INFLAMMATION

Inflammatory conditions can affect the maxillary sinus from odontogenic and nonodontogenic causes.

Odontogenic Sinusitis (Periapical Mucositis)

Etiology

Odontogenic sinusitis is caused by a periapical abscess, cyst, granuloma, or periodontal disease that causes an expansile lesion within the floor of the sinus. Other causes include sinus perforations during extractions and foreign bodies (e.g., gutta-percha, root tips, amalgam). Odontogenic sinusitis is often polymicrobial, with anaerobic streptococci, Bacteroides spp., Proteus spp., and coliform bacilli being involved. Studies have reported that approximately 25% of chronic sinusitis cases may have some odontogenic origin when teeth are present in the posterior maxilla.78,79

Acute Rhinosinusitis

Acute maxillary rhinosinusitis results in 22 to 25 million patient visits to a physician in the United States each year, with a direct or indirect cost of 6 billion U.S. dollars. Although four paranasal sinuses exist in the skull, the most common involved in sinusitis are the maxillary and frontal sinuses.70

Etiology

The most important factor in the pathogenesis of acute rhinosinusitis is the patency of the ostium.80,82 Local predisposing causes of sinusitis include inflammation and edema associated with a viral upper respiratory tract infection or allergic rhinitis. As a consequence, mucous production within the sinus may be abnormal in quality or quantity, along with a compromised mucociliary transport. In an occluded sinus, an accumulation of inflammatory cells, bacteria, and mucus exists. Phagocytosis of the bacteria is impaired with immunoglobulin (Ig)-dependent activities decreased by the low concentration of IgA, IgG, and IgM found in infected secretions.

The oxygen tension inside the maxillary sinus has significant effects on pathologic conditions. When the oxygen tension in the sinus is altered, resultant sinusitis occurs. Growth of anaerobic and facultative organisms proliferate in this environment.83 Many factors may alter the normal oxygen tension within the sinuses. A direct correlation exists between the ostium size and the oxygen tension in the sinus. In patients with recurrent episodes of sinusitis, oxygen tension is often reduced, even when infection is not present. As a consequence, a history of recurrent acute rhinosinusitis is relevant to determine whether an implant may be at increased risk when inserted at the same time as the sinus graft.

Radiographic Appearance

The radiographic hallmark in acute rhinosinusitis is the appearance of an air-fluid level. A line of demarcation will be present between the fluid and the air within the maxillary sinus. If the patient is supine, then the fluid will accumulate in the posterior area; if the patient is upright during the imaging, the fluid will be seen on the floor and horizontal in nature. Additional radiographic signs include smooth, thickened mucosa of the sinus, with possible opacification. In severe cases the sinus may fill completely with supportive exudates, which gives the appearance of a completely opacified sinus. With these characteristics, the terms pyocele and empyema have been applied.

Chronic Rhinosinusitis

Etiology

As maxillary rhinosinusitis progresses from acute to chronic, anaerobic bacteria become the predominant pathogens. The microbiology of chronic sinusitis is very difficult to determine because of the inability to achieve accurate cultures. Studies have shown that possible bacteria include Bacteroides spp., anaerobic gram-positive cocci, Fusobacterium spp., as well as aerobic organisms (Streptococci spp., Haemophilus spp., Staphylococcus spp.).84 A recent Mayo Clinic study showed that in 96% of patients with chronic sinusitis, active fungal growth was also present.85

Allergic Sinusitis

Etiology

Allergic sinusitis is a local response within the sinus caused by an irritating allergen in the upper respiratory tract. Therefore this allergen may be a cause of acute or chronic rhinosinusitis. This category of sinusitis may be the most common form, with 15% to 56% of patients undergoing endoscopy for sinusitis showing evidence of allergy. This condition often leads to chronic sinusitis in 15% to 60% of patients.86 The sinus mucosa becomes irregular or lobulated, with resultant polyp formation.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses