Chapter 33

Temporomandibular Joint Surgery (Including Arthroscopy)

Arthroscopy

Modern arthroscopy started with the commercial introduction of the flexible fiber-light cable in the early 1970s. Another invention, the Hopkins rod-lens telescope, also introduced commercially in the 1970s, constituted a significant improvement in the optics, and arthroscopy of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) began shortly afterwards. TMJ arthroscopy provides unique possibilities for simultaneous intra-articular diagnosis and surgical treatment.

Anatomic Considerations

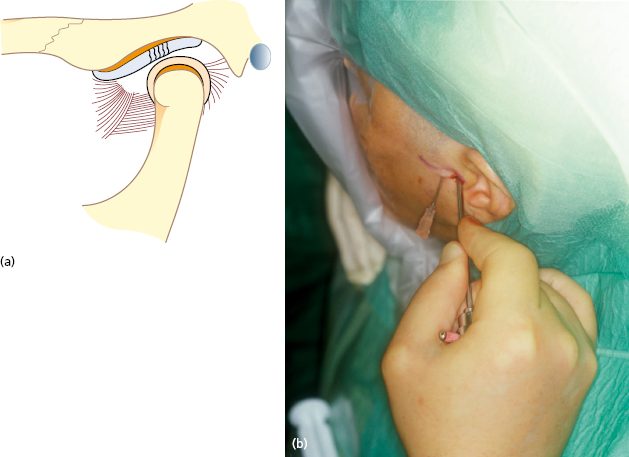

The joint is divided by the disc into an upper and a lower compartment. The volume of the upper compartment is about twice as large as that of the lower compartment. Puncture of the upper compartment involves only trocar penetration of the lateral capsule, while puncture of the lower compartment involves penetration of both the capsule and the disc ligament. Thus, puncture of the lower compartment always involves the slight risk of damaging the lateral disc attachment, which may, in turn, cause displacement of the disc medially. For these reasons arthroscopy is usually restricted to the upper joint space. It is relatively safe to insert the instruments from the lateral side between the temporal vessels posteriorly and the temporal branch of the facial nerve anteriorly.

Diagnostic Arthroscopy

The advent of high resolution MRI has decreased the need for diagnostic arthroscopy. One advantage of arthroscopy is that, depending on the condition, diagnosis and therapy can be performed simultaneously.

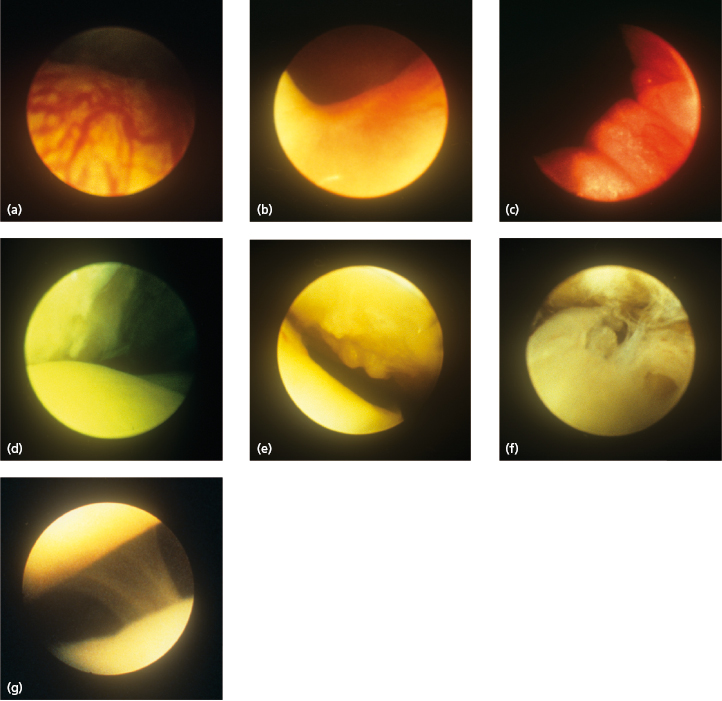

Possible indications for arthroscopic examination (Fig. 33.1) are:

- disc derangements;

- osteoarthritis;

- rheumatic joint disease;

- crystal-induced arthritis;

- synovial pseudotumors.

Arthroscopic examination can also show discal perforations which are not visible on MRI.

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications include:

- bony ankylosis;

- advanced resorption of the glenoid fossa;

- infection in the joint area;

- malignant tumors.

Relative contraindications include:

- patients at increased risk for hemorrhage;

- patients at increased risk for infection;

- fibrous ankylosis.

Arthroscopy Equipment

Figure 33.2 shows a suitable set of instruments. Most telescopes have a diameter of about 2 mm but ultrathin telescopes have been developed with a diameter of about 0.7 mm. Such a reduction in diameter results in a loss of optical quality. There is also an increased risk that the instrument will break. The telescope should have a direction of view of 30°. This allows the field of vision to be increased simply by rotating the instrument. A 1.2 mm disposable standard needle is suitable for outflow. For triangulation purposes a twin sheath is used. This allows for switching the position of the working instruments and telescope. A Xenon cold-light source provides a light with accurate color purity.

Instruments for arthroscopic surgery are:

- forceps, knives, and scissors;

- suction punch;

- mini-shavers;

- bipolar cautery;

- surgical lasers (most frequently Holmium/YAG).

Arthroscopic Procedures

Arthroscopy can be performed under local or general anesthesia.

Puncture

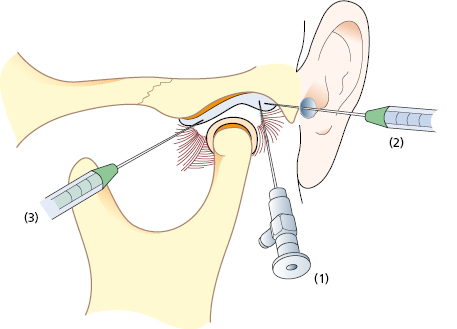

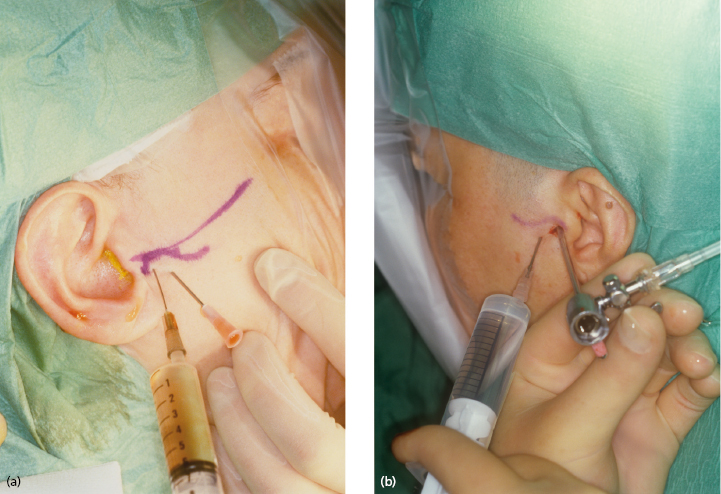

First, the upper compartment is distended with 2 mL of lidocaine which is injected slowly until resistance is felt. The so-called inferolateral approach gains good access to the posterior part of the upper compartment of the TMJ (Fig. 33.3). This is also the best approach for puncturing the lower compartment. The anterolateral and endaural approaches are mainly used when arthroscopic surgery is intended.

Correct placement of the arthroscope should be confirmed through the telescope. An outflow portal is then created (inferolateral approach) about 5 mm anterior to and slightly below the arthroscopic sheath. Continuous irrigation is performed, to ensure a clear field of vision and to keep the joint space extended, using isotonic saline solution. For more prolonged arthroscopic surgery, Ringer’s solution may be a better alternative because it has been found to protect the chondrocytes and maintain the synthesis of proteoglycans.

Arthroscopic Examination (Diagnostic Arthroscopy)

The arthroscopic examination begins with identification of the arthroscopic landmarks – i.e. the boundary between the disc and the posterior disc attachment, the medial capsule, and the inferior part of the eminence, followed by a methodical examination of the joint compartment.

Arthroscopic Surgery

In the field of orthopedic surgery, arthroscopic procedures have increasingly replaced open joint surgery. The duration of the postoperative period and the frequency of complications have thereby been reduced.

However, arthroscopic surgery of the TMJ is more difficult. The anatomic position limits the possibilities for surgery and the small size and the anatomy of the joint often give limited access for the instruments. The introduction of new instruments with fine dimensions and the surgical laser has increased the possibilities for arthroscopic surgery of the TMJ.

Technical Aspects

Minor surgical procedures, such as lysis and lavage or partial synovectomy, can be performed under local anesthesia with or without sedation. The surgical procedures are best performed under direct visual control either with a double cannula or with triangulation.

The following surgical procedures can currently be performed:

- biopsy;

- lavage (Fig. 33.4);

- lysis (Fig. 33.5) ;

- disc repositioning;

- synovectomy (Fig. 33.6) ;

- debridement and abrasion;

- restriction;

- intra-articular pharmacotherapy.

Complications

Possible complications include:

- vascular injury;

- extravasation;

- scuffing of cartilage;

- broken instruments;

- otologic complications;

- intracranial damage;

- infection;

- nerve injury.

Concluding Remarks

Similar to developments in the field of orthopedic surgery, TMJ arthroscopy has become an important method for diagnosis and treatment. Its accuracy in diagnosing TMJ diseases is high and simultaneous biopsy can be performed to improve diagnosis. Complications are minor and infrequent. However, high resolution MRI has made diagnostic arthroscopy less needed, and the small size and complexity of the joint, together with the small size of the instruments has hindered the development of therapeutic arthroscopy.

Open Temporomandibular Joint Surgery

Overall, open joint surgery is indicated in less than 5% of patients with TMJ symptoms. The remainder can be treated non-surgically, or with arthroscopic procedures.

Conditions that may Require Open TMJ Surgery

- Mechanical disorders:

- disc displacement;

- mandibular dislocation.

- Degenerative joint disease.

- TMJ trauma.

- TMJ abnormalities:

- congenital;

- acquired.

- TMJ tumors.

Surgical Approaches to the TMJ

Preparation of the Surgical Site

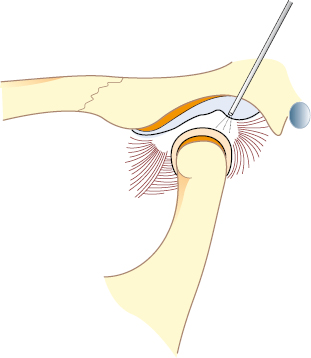

The standard approach to the TMJ is the preauricular approach (Fig. 33.7). It uses the preauricular skin fold and, if needed, may be extended superiorly and slightly anteriorly. Normally, when an intra-articular procedure is intended there is no need for a superior or anterior extension of the incision but in cases where access to the area anterior to the eminence is needed such an extension of the incision is practical.

The dissection continues in layers down to the capsule of the joint, taking care to avoid the zygomatico-temporal branch of the facial nerve. The temporalis fascia is exposed and any vessels running posteriorly are ligated or cauterized. The fascia is then followed inferiorly down to the superior part of the zygomatic arch. The temporal artery and vein may be ligated if they interfere with the exposure of the joint. The auriculotemporal nerve usually runs together with the artery and vein and may be dissected free and retracted anteriorly. The dissection is then continued with an anteriosuperior incision through the superficial layer of the temporalis fascia, which is then extended inferiorly. The scissors are used to identify the zygomatic arch. An almost constant finding is a fairly large vein running over the zygomatic arch in a superior direction. This vein is a useful landmark for the anatomical location of the glenoid fossa. After exposure of the zygomatic arch, the lateral capsule is easily found inferiorly. The structures anterior and inferior to the capsule are protected with retractors. A horizontal incision in the superior part of the capsule provides access to the upper compartment, to perform the definitive surgery. Closure of the incision is made in the usual manner beginning with the lateral capsule and the temporal fascia and then a few sutures in the deeper subcutaneous tissue and finally a running 4/0 subcuticular suture to close the skin.

Surgical Procedures

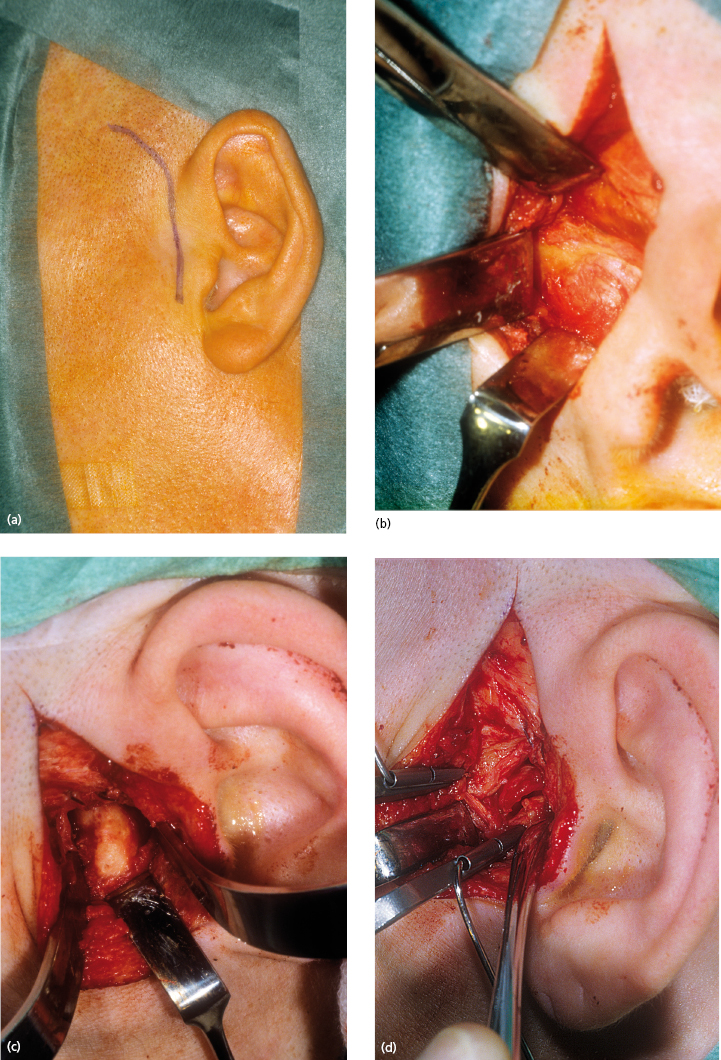

Disc Repositioning

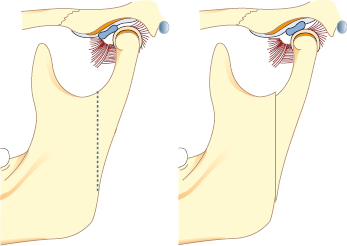

Disc repositioning means that the anteriorly displaced disc is surgically repositioned back to its original position on the condyle (Fig. 33.8).

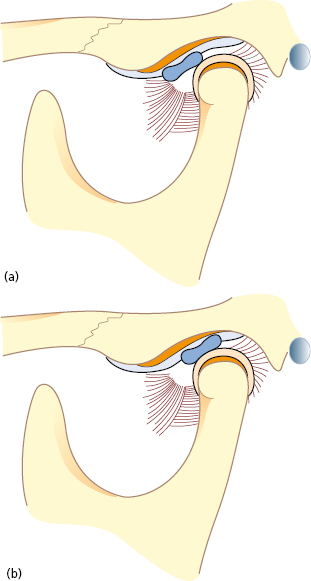

Modified Condylotomy

The hypothesis of this method is that if the position of the condyle is altered, the load on the posterior disc attachment will be reduced, which in turn will facilitate a spontaneous repositioning of the disc on the condyle (Fig. 33.9). In the knee, the same method has been used in the past by performing an osteotomy of the tibia, thereby changing the load on the meniscus.