Assisting in a Medical Emergency

Learning Outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the student will be able to achieve the following objectives:

• Pronounce, define, and spell the Key Terms.

• List the qualifications that a dental assistant must have for emergency preparedness.

• Describe the common signs and symptoms of an emergency and how to recognize them.

• List the basic items that must be included in an emergency kit.

• Discuss the use of a defibrillator in an emergency situation.

Performance Outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the student will be able to meet competency standards in the following skills:

• Accurately perform CPR on a simulated mannequin.

• Accurately perform the Heimlich maneuver on a mannequin.

Electronic Resources

![]() Additional information related to content in Chapter 31 can be found on the companion Evolve Web site.

Additional information related to content in Chapter 31 can be found on the companion Evolve Web site.

• The Interactive Dental Office Patient Case Study: Wendy Ledbetter

• Procedure Sequencing Exercises

• WebLinks

![]() and the Interactive Dental Office DVD

and the Interactive Dental Office DVD

Key Terms

Acute Referring to a condition with a rapid onset.

Allergen (AL-ur-jen) A substance, such as pollen, that causes an allergy.

Allergy (AL-ur-jee) High sensitivity to a certain substance.

Anaphylaxis (an-uh-fi-LAK-sis) Extreme hypersensitivity reaction to a substance that can lead to shock and life-threatening respiratory collapse.

Angina (an-JYE-nuh) Chest pain caused by inadequate oxygen to the heart.

Antibodies Immunoglobulins produced by lymphoid tissue in response to a foreign substance.

Antigen (AN-ti-jen) A substance introduced into the body to stimulate the production of an antibody.

Aspiration (as-pi-RAY-shun) The act of inhaling or ingesting, as of a foreign object.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) (kahr-dee-oe-PUL-muh-nar-ee ree-suh-si-TAY-shun) A planned action for restoring consciousness or life.

Convulsion (kun-VUL-shun) An involuntary muscular contraction.

Epilepsy (EH-pi-lep-see) Neurologic disorder with sudden recurring seizures of motor, sensory, or psychic malfunction.

Erythema (er-i-THEE-muh) Skin redness, often caused by inflammation or infection.

Gait A particular way of walking, or ambulating.

Hyperglycemia (hye-pur-glye-SEE-mee-uh) Abnormally high blood glucose level.

Hypersensitivity State of being excessively sensitive to a substance, often with allergic reactions.

Hyperventilation Abnormally fast or deep breathing.

Hypoglycemia (hye-poe-glye-SEE-mee-uh) Abnormally low blood glucose level.

Hypotension (hye-poe-TEN-shun) Abnormally low blood pressure.

Myocardial infarction (mye-oe-KAHR-dee-ul in-FAHRK-shun) Condition in which damage to the muscular tissue of the heart is commonly caused by obstructed circulation; also referred to as a heart attack.

Syncope (SING-kuh-pee) Loss of consciousness caused by insufficient blood to the brain.

Ventricular fibrillation (VF) (ven-TRIK-yoo-lur fib-ri-LAY-shun) Abnormal cardiac rhythm that prevents the heart from pumping blood.

A medical emergency is a condition or circumstance that requires immediate attention for a person who has been injured or has suddenly become ill. When a medical emergency occurs, it is not possible to refer to a medical textbook for answers. You must be prepared to respond immediately. Your knowledge and skills could mean the difference between life and death.

At the time of a medical emergency, you may be the only person in the area. If this happens, you must initiate first response until the dentist or medical assistance arrives. If this is the case, it will be your responsibility to use well-chosen words of support, to show a willingness to help, and to demonstrate capable lifesaving skills.

Preventing a Medical Emergency

One of the most important ways to prevent a medical emergency is to know your patient. This means establishing open communication about the patient’s health and having a completed or updated medical history before dental treatment is begun.

The front desk assistant (business assistant) is responsible for ensuring that patients update this information as they enter the office. Once they have received the forms, patients should indicate any changes in their health, even if they were seen as recently as the previous week. They should also verify that the information is accurate by dating and signing the form (see Chapter 26 for a review of a medical history update).

Most emergencies that occur in the dental office are caused by the combined stress of a person’s daily life and the apprehension of going to the dentist. If a patient has had a negative experience or is nervous about a specific procedure, the patient’s stress level could be altered, which may lead to a medical crisis. It is important to recognize the areas of dental treatment that are most stressful for the patient.

Emergency Preparedness

While the patient is in the dental office, the dentist is responsible for the individual’s safety. If a medical emergency involving the patient arises, the dentist and staff members are responsible for providing emergency care until more qualified personnel arrive. Emergency first aid protocols must be established and routinely practiced in the dental office.

Successful management of medical emergencies in the dental office requires preparedness, prompt recognition, and effective treatment. Every member of the dental team must be prepared for an emergency when one occurs in the dental office.

Ongoing observation of the patient is an important part of emergency preparedness. A calm, well-functioning staff is capable of handling an emergency in the dental office without complicating the seriousness of the situation by frightening the patient. To prevent added stress and complications, every staff member should know and practice his or her role in emergency protocols before any emergency arises. A standardized procedure for the management of emergencies must be established and followed.

Assigned Roles

In the management of an emergency, the combined efforts of trained persons are more efficient when each person takes on a specific, assigned role. It is the responsibility of the dentist to define these roles. Most often, dental team members are in charge of specific roles:

• Front desk staff (business assistant) will call emergency services and remain on the telephone at all times until appropriate medical assistance arrives (Fig. 31-1).

• A clinical assistant or dental hygienist will retrieve the oxygen unit and emergency drug kit and prepare for use (Fig. 31-2).

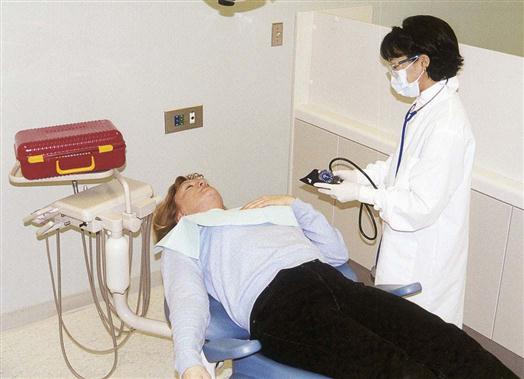

• The dentist, clinical assistant, or dental hygienist will remain with the patient to assist in assessment or with basic life support (Fig. 31-3).

• Additional dental team members will respond to the needs of other patients in the office.

Routine Drills

Training must be kept current at all times. A “mock emergency” should be created in the dental office monthly, so that dental team members can practice their roles, take on additional roles, and refine the office’s emergency plan.

Emergency Telephone Numbers

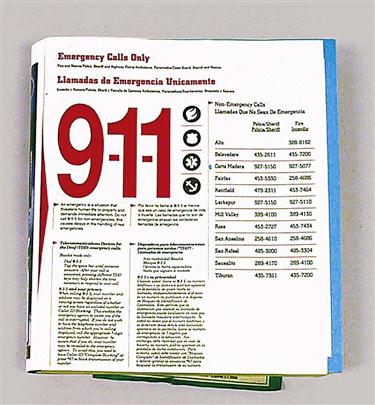

A list of emergency numbers should be posted next to each telephone throughout the office. Maintaining a current list of these telephone numbers is an important part of emergency preparedness.

The list should include telephone numbers for emergency medical services (EMS) personnel, local police, and firefighters. In most areas, all three services can be reached by dialing 911 (Fig. 31-4). The response time and availability in which these services respond to emergencies vary widely according to the geographic area and the population served. Two important factors in emergency preparedness are to know (1) the time it takes for local EMS personnel to reach the dental office, and (2) the life support capabilities that are available on arrival of the EMS staff (Fig. 31-5). Not all EMS personnel carry the same equipment or provide the same level of lifesaving care.

A list of the telephone numbers of the nearest hospital, physicians, and oral surgeons should also be available. These professionals would be able to offer the life support needed while you are waiting for EMS personnel or another type of emergency response.

Recognizing a Medical Emergency

The dental staff must be aware that a medical emergency can occur at any time. For this reason, ongoing observation of the patient in the reception area, in the dental chair, or leaving the office cannot be overemphasized. The “attentive” dental team observes the patient’s general appearance and gait as he or she enters the clinical area. Note the patient’s response to routine questions. Slow responses and changes in speech patterns from a previous appointment should be noted for the dentist to evaluate. Recognition of a problem is critical.

Signs and Symptoms

When a medical emergency occurs, it is important for you to be attentive and take note in the patient’s response of a symptom and your observation of the signs. A symptom is what the patient is telling you about how they feel or what they are experiencing, such as, “I feel dizzy,” “I’m having trouble breathing,” or “My arm hurts.”

A sign is what you observe in a patient, such as a change in skin color or an increase in respiratory rate. Because signs are actually observed by you and/or another member of the dental team, they are considered to be more reliable than symptoms.

Emergency Care Standards

It is imperative that each member of the dental team have the following credentials and skills:

• Ability to assess and record vital signs accurately (see Chapter 27)

• Basic life support for the Health Care Provider (cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR)

Basic Life Support

The fundamental aspects of Basic Life Support include (1) immediate recognition of an emergency, (2) activating the emergency response system, (3) early performance of high-quality CPR, and (4) rapid defibrillation when appropriate.

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

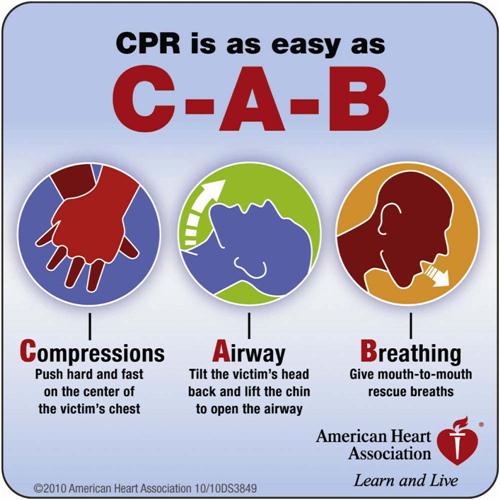

In an emergency in which the patient is not breathing and the heart is not beating, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) must be initiated immediately. The 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for CPR has determined that immediate activation of the emergency response system and starting chest compressions for any unresponsive adult victim with no breathing or abnormal breathing increases CPR effectiveness, and will provide better odds in saving a life. Any rescuer, regardless of their training and background should provide chest compressions to all cardiac arrest victims.

The major change in the way CPR was taught to the new method is the sequence of steps from “A-B-C” (Airway, Breathing, Chest compressions) to “C-A-B” (Chest compressions, Airway, Breathing) for adults and pediatric patients (children and infants). By changing the sequence to C-A-B, chest compressions are initiated sooner and ventilation only minimally delayed until completion of the first cycle of chest compressions.

CPR combines external cardiac compressions to stimulate the heart, with rescue breathing to ensure that adequate air is entering the lungs. This emergency support system must be initiated immediately so that the flow of oxygen-carrying blood quickly reaches the brain. The cells of the brain, the most sensitive tissue in the body, are irreversibly damaged after 4 to 6 minutes without oxygen.

CPR for children and infants is similar to that for adults, but a few changes must be made to adapt to the anatomy and smaller bodies of children.

Emergency Procedure 31-1 reviews CPR for the adult, the child, and the infant.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

inches (4 cm).

inches (4 cm).