Chapter 30

Correction of Dentofacial Deformities

The art and science of correcting dentofacial deformities by means of orthodontic tooth movement and surgical repositioning of the jaw structures is called orthognathic surgery. Orthodontic treatment is primarily the treatment of a malocclusion by the movement of the teeth within their bony base. Most patients with a malocclusion and normal jaw relation can be managed by means of orthodontic treatment alone. However, successful correction of a malocclusion combined with a skeletal discrepancy between the upper and lower jaw is often not possible by orthodontic means alone.

Over the last three decades orthognathic surgery has developed into a science and an art form through the combination of the skills of the specialities of orthodontics and oral and maxillofacial surgery. To optimise the treatment outcomes the support of the general dentist, prosthodontist, endodontist, periodontist and our medical colleagues are, however, often required. Patients with dentofacial deformities are treated with three prime goals in mind:

- Function. Apart from establishing normal masticatory function, the clinicians should also consider other problems caused by an abnormal jaw relationship such as: speech defects; sleep apnoea; attrition of the teeth; periodontal problems; and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) problems.

- Stability of results. Definitive orthognathic treatment is a change for life and it is important to achieve dental and skeletal stability following treatment. Experience has shown that certain orthodontic tooth movements may not be stable in the long term while neuromuscular influence on a repositioned jaw may cause relapse.

- Aesthetics. Facial appearance is often the patient′s main concern. Leo Tolstoy said in Childhood, “I am convinced that nothing has so marked influence on the direction of a man′s mind as his appearance, and not his appearance itself so much as his conviction that it is unattractive”. Aesthetic imbalance is often the result of dento-skeletal imbalance.

The human face is a three-dimensional soft tissue structure supported by bone and teeth and all three dimensions should be considered when evaluating the relationship of the facial soft tissues, the upper and lower jaws to each other and the occlusion. The three basic dimensions are:

- Vertical – The height of the upper and lower jaws and their relationship to facial proportions.

- Horizontal – The antero-posterior relationship between the jaws and its effect on the profile.

- Transverse – The widths of the dental arches, symmetries of the jaws and associated soft tissues.

A surgical orthodontic treatment is the only approach indicated for the successful correction of severe dentofacial deformities. However, the treatment of some malocclusions combined with mild skeletal disharmony is possible by orthodontic compensation of the dentition. Inappropriate dental compensation may, however, lead to poor long-term dental stability and compromised facial aesthetics. Borderline cases, therefore, require meticulous assessment before finally deciding on orthodontic treatment alone or a combination of orthodontics and surgery as treatment approach. Which treatment plan to adopt should be discussed with the patient (and perhaps the parents or spouse) and all the advantages and disadvantages of each approach explained. The decision may also be influenced by factors such as: the orthodontists experience; financial insurance cover; available surgical expertise; and the patient’s attitude and preferences.

The family dentist is often the first clinician to recognize and diagnose the patient’s dentofacial deformity. It is most helpful if the dentist has a basic knowledge of the diagnosis, treatment planning, sequence of treatment, treatment possibilities and outcomes, and an overview of orthognathic surgery procedures to begin the process of educating the patient. This instils confidence in the patient vis-á-vis future treatment and subsequent referral to a specialist.

A meticulous and comprehensive assessment of the patient is required before formulating a treatment plan. An orthognathic assessment will consist of the following:

- History. The patient′s medical history can be obtained by means of a questionnaire that the patient fills out at the first visit. Previous restorative, orthodontic, and periodontal treatment and facial pain including TMJ pain should be reviewed.

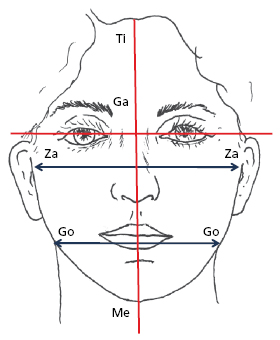

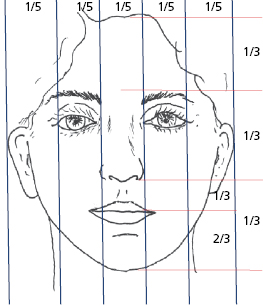

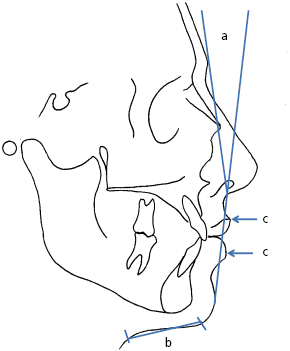

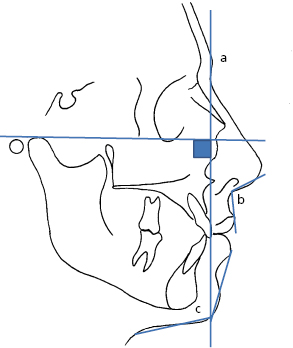

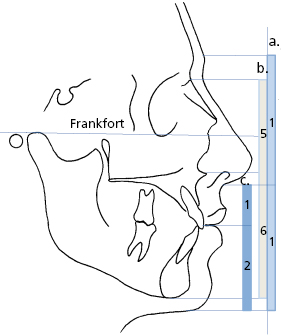

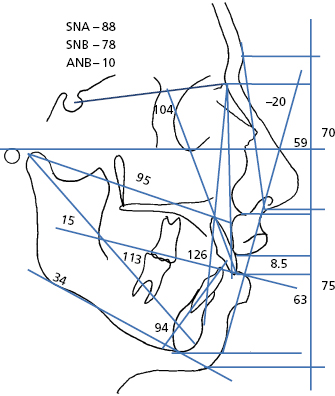

- Clinical evaluation. The clinical assessment of the face is probably the most valuable of all diagnostic procedures. While an astute clinical diagnosis can be made at the chair side, photographs are essential for accurate assessment and record purposes. The face is systematically assessed from a frontal view, profile view, three-quarter view. Figures 30.1, 30.2, 30.3 and 30.4 illustrate some angular and linear parameters used during the clinical assessment of the face.

- Special investigations. Cephalometric and panoramic radiographs and dental casts are essential; however, TMJ investigations, Technetium bone scans, hand wrist radiographs, CT scans, etc. may be required. The lateral cephalometric radiograph allows the clinician to analyze and evaluate the soft tissue, skeletal and dental relations of a dentofacial deformity (Fig. 30.5).

- Diagnosis and problem list. A diagnosis is made following the clinical evaluation of the patient, a radiographic evaluation and cephalometric analysis, model analysis and other indicated evaluations. The data base is used to compile a problem list.

- Treatment objectives. Clear orthodontic and surgical treatment objectives regarding soft tissue, skeletal and dental structures should be identified and noted.

- Development of a visual orthodontic and surgical cephalometric treatment objective. The lateral cephalometric radiograph tracing is used to develop an orthodontic visual treatment objective to predict orthodontic tooth movements. This is followed by the development of a surgical visual treatment objective predicting the required jaw repositioning and expected soft tissue changes (see individual Cases).

- Treatment plan. All the factors identified in the diagnosis and problem list as well as patient concerns and reasons for considering orthognathic surgery are taken into account to formulate a final treatment plan. The sequence of treatment and the treatment to be performed by all health care professionals concerned are outlined. It is essential that when defining the treatment plan, a thorough knowledge of the many types of dentofacial deformities and the treatment modalities available to correct them is essential.

- Treatment. Although the orthodontist and the oral and maxillofacial surgeon are the main role players, comprehensive correction of dentofacial deformities may involve several members of the health care team. It is mandatory that the therapeutic management is carried out as planned and any problem or change in treatment plan should be communicated to the treatment team.

Explanation of A Typical Treatment Profile

Once a definitive treatment plan has been formulated, it is discussed with the patient and, once accepted, treatment can commence. A typical orthognathic treatment profile consists of six phases:

- Placement of orthodontic bands and attachments on the teeth. Any extractions of teeth (including third molars) are performed 2–3 weeks before the orthodontic appliances are placed.

- Preoperative orthodontic phase. The teeth are now aligned in their optimal positions according to the treatment plan. This phase usually takes 9–18 months. Once the orthodontist is satisfied that the preparation is complete, the patient is referred back to the surgeon.

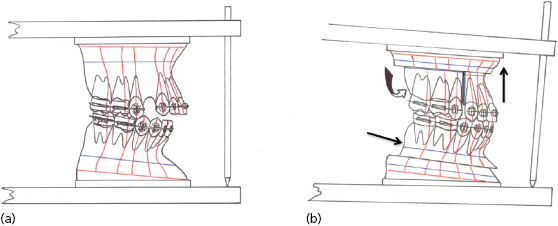

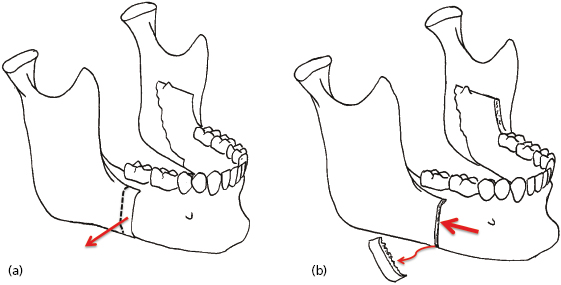

- Surgical phase. Before surgery a new set of orthognathic records are obtained. A final surgical cephalometric visual treatment objective is developed and the exact required surgical movements measured on the tracing (Fig. 30.6). Modern technology allows the surgeon to obtain three-dimensional images through CT scanning of the face. Surgical planning can be performed using these images. For the treatment of more intricate dentofacial deformities three-dimensional models can be fabricated from the CT scans to further enhance planning. New dental moulds are taken and the casts accurately articulated on an adjustable articulator. The intended surgical movements are performed on the plaster models and the surgical movements of the jaws and teeth again measured (Fig. 30.7). Acrylic surgical splints are now fabricated on the models. The surgical splints will guide the surgeon during surgery. The jaws are now surgically repositioned according to the treatment plan. Immediately following surgery light intermaxillary elastics (3.5 oz, 2.5 mm) are placed to guide the teeth into the new occlusion and the patient is advised to maintain a soft diet for 3–6 weeks. Modern orthognathic surgery practice very seldom requires intermaxillary wire fixation. The patient is referred back to the orthodontist 2–3 weeks after surgery.

- Postoperative orthodontic phase. The occlusion is now refined until the orthodontist is satisfied that maximum intercuspation has been achieved.

- Removal of fixed orthodontic appliance. Once the orthodontist is satisfied with the occlusion, the orthodontic appliance is removed.

- Retention phase. The retention phase for orthognathic cases are basically the same as for all orthodontic cases.

The face is an intricate three-dimensional structure and restoring balance amongst the different parts will re-constitute facial beauty. The diagnosis must identify which components are out of balance, for apparently similar appearances may be the result of differing structural problems (Fig. 30.8).

For convenience the facial deformities are discussed as they affect the antero-posterior, the vertical and the transverse planes of the face. Although facial deformity is often t/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses