Morphopsychology and Esthetics

Claude R. Rufenacht

The evaluation of human beauty

No apparent characteristic difference exists in the esthetic appearance of the various morphologic types. Beauty is not limited to either sanguines or lymphatics, relegating the others to ugliness. The perception of beauty in the various types depends upon racial, ethnic, civilization, and individual factors. Generation, vogue, and fashion factors may contribute to actualize and favor, at any given moment, the esthetic preference for a specific directional expansion of a facial zone, but beauty basically depends upon the harmonious integration of the esthetic principles described earlier, and it is greatly influenced by the importance of psychologic factors that (radiating from individuals) may enhance or affect esthetic appearance.

“Aucune grâce extérieure n’est complète si la beauté intérieure ne la vivifie. La beauté de I’âme se répand comme une lumière mystérieuse sur la beauté du corps.”

(Victor Hugo)

“Physical beauty is incomplete without the animation provided by interior beauty. Like an occult light, the beauty of the soul infuses bodily beauty.”

Everyone has a mental picture of his or her own appearance in space, and this self-image directly depends on a multitude of factors that influence the intellect. Magazines, media, ethnic habits, racial factors, and environment develop standards of beauty to which any individual tends to conform. In our highly conditioned Western society a considerable effort can be observed for the maintenance or perfection of appearance and well-being in adopting a personal philosophy of life where physical and psychologic factors should bring a certain equilibrium. Any individual is a collection of dynamism, and the importance that the individual gives consciously or unconsciously to the perception of esthetic problems and self-image depends on the strength of those dynamic forces and the field of interest to which they are directed. Beauty, in which utility and pleasure have been philosophically integrated as additional values, is at the center of all human aspirations. Self-satisfaction without vanity that invariably reflects on an individual’s facial appearance appears as the consequence of efforts to achieve and realize goals and as the result of a favorable psychologic reaction induced by body and self-image perception (Figs 3-1 to 3-4).

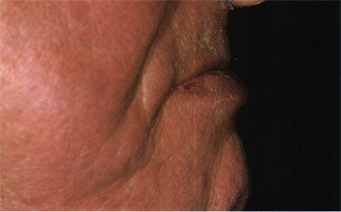

Fig 3-1 Excessive tooth wear, combined with changes affecting muscle and tegumental maintenance, have resulted in this clinical situation, illustrated by the depression of the corners of the mouth and the effacement of the upper lip.

Fig 3-2 A pronounced and unesthetic nasolabial ridge surrounded by deep labial and nasolabial grooves and an unusual extension of the mentolabial groove strengthen this image of facial deterioration.

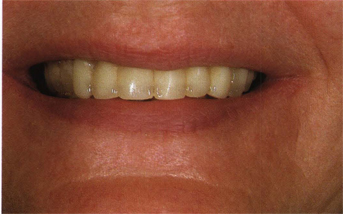

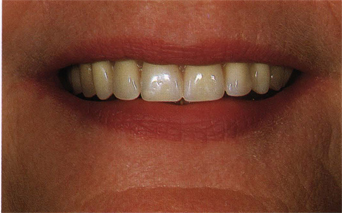

Fig 3-3 The restoration of original lip design and the restoration of the position of the corners of the mouth in the vertical plane have to be expected following oral rehabilitation.

Fig 3-4 The simultaneous effacement of facial traits resulting from oral pathologies has to be achieved. Note the effacement of the nasolabial ridge and that of the labial groove. The nasolabial groove remains unaffected by intraoral therapeutic measures.

The body image concept may develop progressively in young children under the protective environment of the family. Handicaps or disfigurement may take place abruptly during school years. This traumatic experience will induce a variety of character changes. An impaired self-image may be more disabling from a developmental aspect than the patient’s real physical defect. The impact of facial image that cannot escape self-esthetic evaluation, through an abundance of existing comparative elements, may generate negative self-images. The more attention is focused on a particular area, the more people tend to acquire a negative self-image relative to this area. In general, the clinician is not aware of the degree of perception of dentofacial disfigurements by the patient. Its restoration in terms of its potential benefit to mental health may be underestimated. These are the reasons why it appears illusory to undertake any dentofacial restoration, no matter how “artistic” or technical it would be if we are not able to understand and interpret the reality expressed by a countenance and the form of personality manifested. A sanguine, sociable, and outgoing individual who would be deprived of a smile by a dental composition not adapted to the psychologic profile, or a withdrawn, timid individual to whom a sparkling smile would be given, would not be models of harmonious facial composition. Such an imbalance would be perceived by the person’s entourage and, above all, by the person. In turn, this could produce a profound influence on the person’s psyche.

The facial map (and with it the mouth) undergoes progressive and various morphologic changes during a lifetime, indicating an individual’s reactions to life events and character maturity. Clinical practice widely demonstrates that the influence of oral pathologies not only accelerates but deeply accentuates these morphologic changes, causing erroneous morphopsychologic and esthetic perception (Figs 3-5 and 3-6). This suggests our professional implication in the restoration of a facial appearance, reflecting both esthetic harmony and morphopsychologic equilibrium in conformity with the patient’s needs and desires. In effacing the negative impacts of life that affect body image perception, physical and psychic radiance will be naturally restored (Figs 3-7 and 3-8).

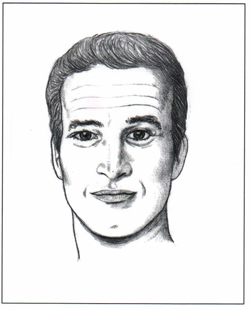

Fig 3-5 Sketch of an individual in his 30s exhibiting well-maintained facial traits, with a marked expansion of the lower third of the face, reflecting a capacity for physical activities.

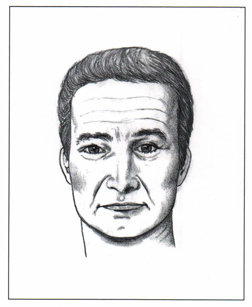

Fig 3-6 The same individual in his early 50s showing a decrease of the lower facial zone with pronounced facial traits, manifestations of oral pathologies, which alter the evaluation of his morphopsychologic profile.

Fig 3-7 In a large number of individuals the physical appearance reflects neither the true age nor personality.

Fig 3-8 Adequate oral rehabilitation has a direct impact on the restoration of physical and psychic radiance.

Until the latter part of the nineteenth century, people were considered adults wh/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses