Chapter 27

Maxillofacial Bone Fractures

Evaluation of Patient with Maxillofacial Injuries

Maxillofacial fractures are often seen in combination with more severe, sometimes life-threatening, injuries, and often require hospital resources. When a trauma patient with maxillofacial injuries arrives in a hospital emergency room, life-threatening injuries must be addressed first. In most hospitals today there are trauma teams with many specialists participating. Specialists dealing with trauma patients undergo special training and work according to guidelines for advanced trauma life support (ATLS), where the principle is treating the greatest threat of life first and indicated life-threatening emergency treatment should not wait for definite diagnosis. Airways must first be secured, either by inserting a nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal airway. Sometimes an endotracheal intubation, or even surgical access to the trachea, has to be performed. Excessive bleeding must be stopped and evaluation of neurological injuries and the cervical spine are important at an early stage. The patient must be stabilized and the vital signs, such as pulse and blood pressure, checked before all regions of the body are carefully evaluated.

After the lifesaving phase, a brief history can be taken from the patient, if conscious. However, if the patient is unconscious an accompanying person or a witness to the accident may give some information. It is important to register when, where and how the injury occurred as well as symptoms and changes. The patient may guide you to the correct examination if you listen to their history carefully. It is also important to obtain a medical history with information about, for example, medication and allergies.

A full maxillofacial examination is performed which includes the facial skeleton, scalp, eyes, ears, nose and oral cavity. Examining and treating the oral and maxillofacial region must be done in a sequential way. The principle is to examine from outside towards inside, whereas treatment of the oral and maxillofacial region is best performed from inside towards outside, if possible.

The evaluation comprises inspection and palpation. Vision, pupils and ocular movements may indicate injuries in the orbital region. Motoric function of facial muscles and masticatory muscles and sensoric evaluation of the facial region is performed. Inspection for hematoma and ecchymoses is included in the examination (Fig. 27.1) and palpation of all bone margins and rims, looking for tenderness or steps in bone contours or crepitation sounds. The naso-orbital-ethmoidal (NOE) region is carefully assessed for hematoma, telecanthus (widening of intercanthal distance medially) or changes in the lateral canthus indicating fracture (Fig. 27.2). The mandibular opening capacity is assessed and the TMJ region is palpated. Finally, the intraoral examination is carried out with inspection for hematomas, teeth and occlusion and palpation of the alveolar process. For evaluation and treatment of traumatic dental injuries and soft tissue injuries, see Chapters 26 and 28, respectively.

Mandibular Bone Fractures

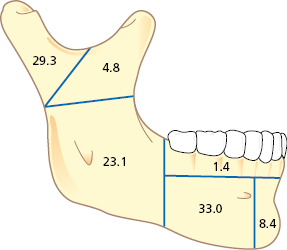

Fractures of the mandible comprise 10–25% of all facial fractures. Figure 27.3 depicts the percentage of mandibular fractures based on anatomic location. The condyle, angle and body are the most common anatomic locations. Frequent combinations of multiple mandibular fractures are angle and contralateral body, bilateral angle or body, and condylar and contralateral body.

Classification and Terms of Mandibular Fractures

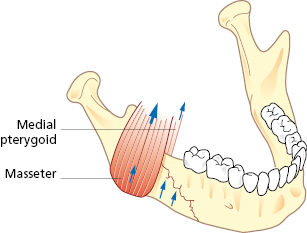

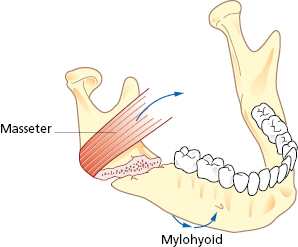

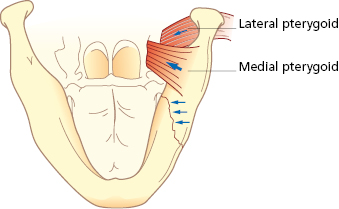

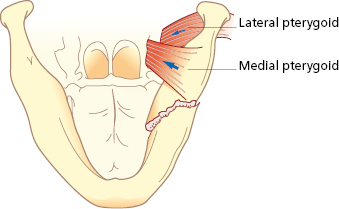

Mandibular fractures are classified and named after anatomic region or fracture pattern and there are also terms associated specifically with temporomandibular joint (TMJ) fractures (Table 27.1). Angle and body fractures can be classified as favorable or non-favorable. If the fracture resists the pull of the segment by the muscles it is considered a favorable fracture. If the muscles tend to pull the segments apart it is an unfavorable fracture (Figs 27.4, 27.5, 27.6, 27.7).

Table 27.1 Classification of mandibular fractures.

| Anatomic region |

| Symphysis – fracture involving the area between the lateral incisors extending vertically through the inferior border of the mandible |

| Parasymphysis – fracture between the mental foramen and the mesial aspect of the canine extending through the inferior border of the mandible |

| Body – fracture between the mental foramen and the distal aspect of the second molar extending through the inferior border of the mandible |

| Angle – fracture between the distal aspect of the second molar and the posterior attachment of the masseter muscle extending through the inferior border of the mandible |

| Ramus – fracture extending horizontally through the anterior and posterior borders of the ramus or extending vertically from the sigmoid notch to the inferior border of the mandible distal to the second molar |

| Condylar process – fracture extending from the sigmoid notch to the posterior border of the ramus |

| Coronoid process – fracture involving the coronoid process |

| Alveolar – fracture confined to the tooth-bearing segment of bone |

| Fracture pattern |

| Greenstick – fracture through one cortex and no discontinuity of bone. No mobility of fractured segments. Common in children |

| Simple – fracture does not communicate with the external environment. A closed fracture |

| Compound – fracture communicates with the external environment either through the skin or the periodontal ligament of a tooth. An open fracture |

| Comminuted – multiple segments of bone as a result of greater force from the trauma |

| Complex – fracture involving damage to adjacent structures |

| Telescoped or impacted – one fractured segment is driven into the other segment |

| Pathologic – fracture resulting from normal function in an area of diseased bone |

| Terms associated with temporomandibular joint (TMJ) fractures |

| Displaced – movement of the condylar (proximal) segment relative to the remainder of the mandible. Although the condyle is malpositioned, it is still within the confines of the glenoid fossa and has not ruptured the capsule of the TMJ |

| Dislocated – the condylar (proximal) segment is no longer within the confines of the glenoid fossa |

| Extracapsular – fracture not involving the capsule of the TMJ |

| Intracapsular – fracture occurring within the TMJ capsule |

Patient Evaluation

A number of signs and symptoms are highly suggestive of a mandibular fracture (Table 27.2). Occlusal changes are one of the most common physical findings in patients with fractures of the mandible. Occlusal changes may be the result of dental fractures, fractures of the alveolus, trauma to associated structures of the TMJ, fractures of the maxilla, or contusions of the masticatory muscles. It is important to consider that the patient may have had a pre-existing malocclusion prior to the injury.

Table 27.2 Signs and symptoms of mandibular fractures.

| Occlusal changes |

| Deviation on opening |

| Altered range of motion |

| Localized pain |

| Lacerations, ecchymosis, or hematoma |

| Neurosensory deficits of the inferior alveolar nerve |

| Changes in facial contour or mandibular arch form |

| Blood in external auditory canal |

| Mobility of bone segments/palpable step-offs |

Deviation of the mandible on opening is indicative of a condylar fracture. In a unilateral condylar fracture, the mandible deviates to the side of the fracture due to the unopposed action of the lateral pterygoid muscle on the unaffected side and the lack of translation on the affected side. An open bite subsequently develops on the unaffected side and the posterior teeth contact first on the affected side. When bilateral condylar fractures occur the mandible does not necessarily deviate. However, the posterior occlusion does contact prematurely and an anterior open bite subsequently develops.

An altered range of motion can occur with mandibular fractures. The most common cause of limited opening is from pain and reflex guarding associated with the trauma. Decreased opening also occurs when a depressed zygomatic arch fracture mechanically impinges upon the coronoid process of the mandible. Muscle contusions and edema overlying any fracture site can also contribute to limited mouth opening.

Hematoma from contusion injuries or lacerations may be associated with either dental or alveolar fractures or they may indicate an underlying mandibular fracture. A laceration to the chin should raise the surgeon’s suspicion for not only a symphysis fracture, but also subcondylar fractures. Sublingual ecchymosis is also consistent for a mandibular fracture.

Imaging

When an isolated mandibular fracture is suspected, the routine radiographic assessment may consist of a panoramic radiograph. A panoramic radiograph is the single most comprehensive image and usually allows for satisfactory visualization of all regions of the mandible (condyle, ramus, body, and symphysis). It is also useful for examining the existing dentition, and showing the presence of impacted/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses