Chapter 24

Management of Patients Undergoing Radiation and Chemotherapy

Radiotherapy

The aim and purpose of radiation therapy in the treatment of head and neck cancer may be two-fold:

- the target (cancer) is either a primary tumor with or without regional spread to the regional lymph nodes;

- the target is clinically and radiologically tumor-free lymph nodes of the neck, but with a high risk of micrometastasis.

Occasionally radiotherapy may also be used to treat benign tumors, such as ameloblastomas or pleomorphic adenomas, when other treatments may be detrimental.

The intention of radiotherapy may either be curative or palliative. When the intention is to cure the patient from the disease, the radiation may be given either as a single modality if the cancer is small, i.e. stage I and II, or as a complement to surgery. When combined with surgery, it may be given prior to, or after surgery. Radiotherapy can also be given in combination with chemotherapy, with a curative intention. When the radiotherapy has a curative intention, the radiation is given at small doses (1–2 Gy) once or twice a day for a period of 3–7 weeks.

When the cancer is not curable, the intention of radiotherapy may be palliative, i.e. it can be used to reduce the symptoms of the disease, e.g. reducing pain emanating from skeletal metastasis, relieving pressure on vital organ systems. When the radiotherapy has a palliative intention, higher doses are given each time, to reach an effect faster. Palliative radiotherapy can improve the quality of life during the last months of life of a patient with an incurable cancer.

Radiation involves the transport of energy, either as electromagnetic waves (photons) or as a beam of particles (electrons or protons). The position of the tumor determines which type of radiation to be used. Particle beams normally have a shorter range, implying that such radiation is used when the cancer is located relatively superficially in the tissues. In contrast, photon radiation is used when the tumor is located more deeply in the tissues.

When radiotherapy is given as a single modality therapy, a lower dose is given to local lymph nodes in order to prevent and sterilize micrometastasis and a higher dose is administered to the known primary tumor, i.e. the cancer. If, on the other hand, radiation is combined with surgery, a smaller dose is given with the aim of sterilizing potential micrometastasis in local lymph nodes.

Conventional radiotherapy implies that the primary tumor as well as the larger lymph nodes of the neck are irradiated with up to 70 Gy. The radiation is given in single fractions of 1.8–2.0 Gy on a daily basis for 6–7 weeks.

Altered fractions have recently been shown to achieve better control both locally and regionally. Hyperfractionation is where 1.2 Gy is given twice a day for about 6–7 weeks, and accelerated fractionation means that 1.6 Gy is given twice a day for about 6 weeks. A third alternative may be accelerated fractionation with a concomitant boost given as 1.8 Gy a day for 6 weeks and during the last 12 days an additional 1.5 Gy is given daily as the boost.

Recently a new form of radiotherapy has been introduced, IMRT (intense modulated radiotherapy). This technique is built on a computer-generated three-dimensional image which allows delivery of high doses of radiotherapy to clinical target volumes, still preserving some critical normal structures, for instance salivary glands.

Brachytherapy

Interstitial radiotherapy, or brachytherapy, is administration of irradiation by implantation of a radioactive material very close to, or inside, the primary tumor. A frequently used substance is iridium (192Ir). The time-span of the treatment may vary between a few seconds to a few days, depending on the type of cancer.

Small tumors, without a risk of spreading to the regional nodes, may be treated with brachytherapy only. In cases where the tumor is of larger size or invades surrounding tissues or structures, as well as when there is a risk of spread to regional lymph nodes, brachytherapy is used to deliver a final boost to the primary tumor after an initial more moderate external dose. Brachytherapy is sometimes used as the final part in the treatment of cancer in the base of the tongue and in the tonsils. Brachytherapy can also be used when there is a palliative intention, for instance in the treatment of laryngeal cancer.

Chemotherapy

The use of drugs in the treatment of head and neck cancer is still a matter of debate. Despite considerable research, there is no drug or combination of drugs available today that can cure solid cancers in the head and neck region. In general oncology, chemotherapy is given either to cure cancer, or to reduce the speed of progression, or to ameliorate the symptoms. Sometimes chemotherapy is also administered to reduce the risk of recurrences, so-called adjuvant treatment.

Chemotherapy is generally used prior to (induction), or parallel (concomitant) to radiotherapy. The purpose of chemotherapy is to kill the cancer cells, or at least impede their growth.

Side-Effects

Radiotherapy

The side-effects of radiation therapy can be divided into acute, but mostly reversible, effects, and late, more commonly irreversible, conditions. The acute side-effects almost always decline within 4–6 weeks after completion of radiation, whereas the late effects can develop after different periods of time and they will also almost always last for the rest of the patient’s life.

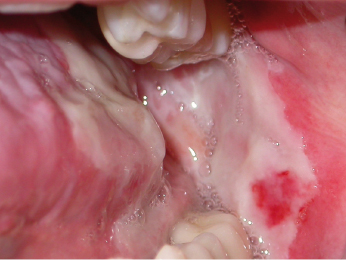

Among the acute effects, an inflammatory reaction in the mucosa (Fig. 24.1) of the oral and pharyngeal mucosa – mucositis – is the most common. The appearance of the mucosa can vary from an increased redness, to an intense reddish appearance, to white necrotic lesions. The damage to the oral mucosa can also make it more susceptible to both bacterial and fungal infections. These conditions are almost always associated with varying degrees of pain, and may need relatively strong analgesics.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses