Chapter 23 Spread of Dental Infection in the Head and Neck

SIGNIFICANT COMPLICATIONS AND IMPLANT DENTISTRY

The principal routes for the spread of dental infection are through the following four mechanisms:

PATHOLOGIC ENTITIES

The definitions of specific terms that describe infections of the head and neck provide keys to methodology of treatment and improved communications. An acute cellulitis involves diffuse inflammation of the areolar connective tissue and loose subcutaneous tissues. Lymphadenitis is a condition in which the regional lymph nodes become inflamed, enlarged, and tender. The node may become suppurated, break through the capsule, and involve the surrounding tissues. Abscess formation results when tissues break down and leukocytes die, thus forming pus. Staphylococci and streptococci are the usual bacteria involved in this process; however, a more varied population is prevalent in sinus infections. Phlegmon is any cellulitis that does not go on to suppuration. In this condition, the inflammatory infiltration of the subcutaneous tissue leads to accumulation of foul-smelling, brownish exudate. Hemolytic streptococci are usually present. A chronic cellulitis follows an acute cellulitis and may be the result of inadequate treatment or a subvirulent organism with no suppuration. A chronic abscess is a well-encapsulated entity caused by a subvirulent organism. In this case, a bone sequestrum or retained root tip is the more common source of the infection. A chronic skin fistula is a sign of retained focus of infection and, in some cases, a more serious condition of bone and bone marrow inflammation called osteomyelitis (Figure 23-1). This has been observed in the mandible and is associated with infection of both endosteal and subperiosteal implants in patients who have poor dental awareness and lack of implant maintenance. A noma starts as a gangrenous stomatitis and spreads to adjacent bone and muscles, causing lysis and necrosis of tissue. This rare condition perforates the cheek, floor of the mouth, or both, and is usually seen in debilitated individuals.

MAXILLARY INFECTIONS

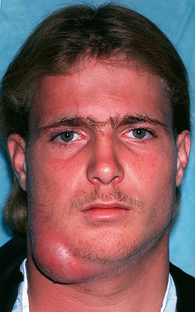

The loose, fat-containing connective tissue of the lips and cheeks is continuous and is traversed by the muscles of facial expression, which arise from the bones of the face, traverse the subcutaneous tissue, and end in the skin. These muscles, with their thin perimysium, play a role in directing the spread of infection. Dental or implant abscesses that erode and perforate the facial alveolar compact bone sometimes find their way through the subcutaneous tissue and produce remarkable swelling of the upper lip and cheek and may spread to the lower and upper eyelids due to the lack of fascial barriers on the face (Figure 23-2).

Most often, maxillary dental infections involve four regions of the maxilla: the upper lip, canine fossa, buccal space, and infratemporal space. The most common maxillary implant-associated infection is in the buccal space (Figure 23-3).

Figure 23-3 Buccal surgical space infection with spread to the submandibular space.

(From Hupp JR, Tucker MR, Ellis E: Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery, ed 5, St Louis, 2009, Mosby.)

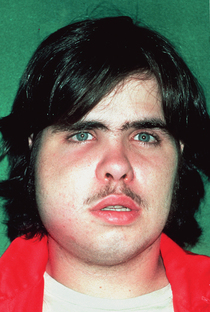

Infection of Buccal Space

Abscesses of the second and third maxillary molars above the attachment of the buccinator frequently involve the buccal space. The infection may extend superiorly to the temporal space, inferiorly to the submandibular space, or posteriorly to the masticatory spaces (Figure 23-4).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses