2

Determinants associated with creating fearful dental patients

The dental experience is a multifaceted combination of physical, emotional, psychological, cognitive, socioeconomic, and vicariously learned factors and situations. These cues are in some manner or form the cause of a biological, psychological, and emotional response, which can include behavior that impedes dental care. A patient’s response to these cues is directly proportional to the degree of severity of a patient’s initial encounter with the fear-evoking cue or stimulus. In turn, these responses are affected by other etiological factors that combine to influence not only the behaviors of everyday life, but also one’ s response to needed dental care. These factors influence both one’s physiological and psychological responses to the dental encounter, and the great variety of behavioral reactions associated with dental treatment or lack of it. How do these many determinants responsible for a person’ s fear, avoidance, or delay of treatment affect the chairside practitioner’ s efforts to overcome the poor dental health of some of his or her patients? To answer this question, and to begin to develop a successful chairside dental fear amelioration program, it is important to examine each of these causative factors and the clinical findings associated with them. Over the years, my own technique has been to study the findings of each of the factors listed below, and to investigate clinically how they affect clinical care and impede a practitioner’ s ability to perform treatment. The objective is to find a characteristic most common to the etiological factor in each determinant (e.g., pain-related fear from prior trauma). The greater goal is to combine these common findings to fit individual patients’ needs as the practitioner collects past and present history pertinent to successful patient management and positive treatment outcome. Granted, practitioners often tend to ask questions that are not necessary, which may cause individuals to hold back information they might otherwise have provided had the questions had been properly designed, but a simple effort to help gather sufficient information about a patient will play an important role in helping to overcome his or her fear of treatment and ensure treatment compliance and success. It is my goal that in following this theme, this text will be more beneficial to the practicing chairside clinician.

The problem of fear of dental treatment as it existed in the past, and as it exists today, has changed little, despite the advances in dental procedures, equipment, and anesthetic technology. Numerous studies over the years, have documented this phenomenon, claiming that 3%–5% of the population suffer from dental phobia, while some 40% of the adult population have been reported to suffer from fear of dental treatment.1–4

As far back as 1978, Kleinknecht5 concluded that one could use the number of missed and cancelled dental appointments to calculate the prevalence of fear of dental treatment. Gatchell et al. noted in 1982 that the prevalence of dental fear and avoidance of routine dental care reached almost as high as 50%–70%.6 In 2001, Lockeret et al.,7 in a discussion of psychological disorders in a young adult population, mentioned that epidemiological studies suggest that between percent(20%) of that segment of the population have levels of fear and anxiety regarding dental treatment that can be problematic. Cohen, Fiske, and Newton8,9 noted in 2000 the prevalence of dental fear and anxiety in the United Kingdom, indicating that studies found about one-third of the adult population to be dentally anxious. Milgrom et al. in 1985, also noted the extent of dental fear and its effect on dental treatment.10 In 1988, Domoto et al found that 80% of Japanese college students claimed to fear dental treatment in varying degrees, while 6% to 14% stated they were terrified of going to the dentist.11 The same range has been found in other studies involved in examining the prevalence of dental fear and anxiety.

As dental practitioners, we are faced with a phenomenon that knows no limit and affects almost everyone, causing stress to the practitioner and possibly having widespread general and oral health consequences. Therefore, our search for the answer to the best way to lessen fear should begin with when and how an individual develops a fear. Since no one is born fearful, it follows that fear of dental treatment must be either learned as the result of a direct experience with dental care, or from an external source within the psychosocial environment. Two common concepts must be considered in discussing the development of the dentally fearful individual:

- the role of direct conditioning; and

- the development of the approach-avoidance conflict.

This method is most likely to cause an individual to develop fear of direct trauma or an accidental slipping of the drill. Such an incident may result in intense pain, or a negative interpersonal interaction between the patient and the dentist. Either way, the patient comes to regard dentistry or some aspect of it as being either unpleasant and perhaps even terrifying. This experience then acts as the initial stimulus triggering a specific emotional response, namely fear. If the dental practitioner fails to respond to the adverse emotional and behavioral response and discomfort caused by this incident, the patient may then appraise the event in a negative manner, thus initiating the development of a negative conditioning factor, resulting in the patient’s avoiding the unpleasant experience and dental care. A new habit is created that may negatively affect the patient’s oral and general health in the future. Milgrom and Weinstein et al.10 present the development of fear and avoidance of dental treatment in a slightly different manner. They illustrate how direct experiences through simple conditioning can lead to fear and avoidance of dental care.

(The following paragraph has been printed with the express written permission of the authors, Dr. Philip Weinstein, a co-author of Treating Fearful Dental Patients: A Patient Management Handbook.)10

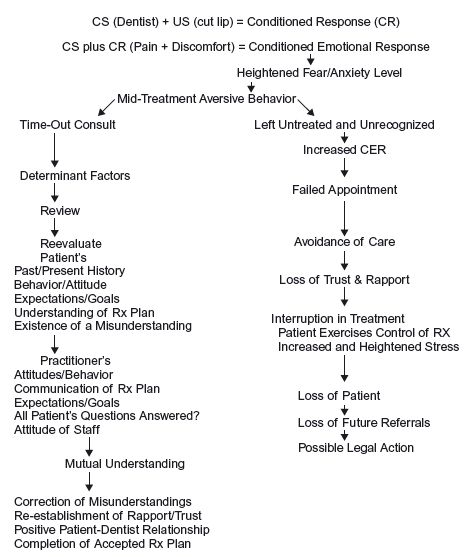

Simple conditioning12 results from the formation of an association between a conditioned stimulus (CS) —the dentist — and a response from an unconditioned stimulus (US) — cut lip from the dental drill. The original response to the unconditioned stimulus (cut lip) is called a unconditioned response (UR). The learned response to the conditioned stimulus (the dentist) is called a conditioned response (CR). The strong emotional component expressed as fear and avoidance that develops is called a conditioned emotional response (CER). The conditioned response (CR) results by associating a conditioned stimulus (CS) the dentist with an unconditioned stimulus (US) the cut lip. The (CER) that follows is developed by associating the pain and discomfort with a second stimulus, which serves to cause the patient to avoid similar encounters again. That stimulus could be the drill, the needle or the dentist’ s attitude. Continued anticipation of a dental encounter accompanied with continued fear and avoidance of the CS serve to reinforce and strengthen the CER, namely in the form of heightened fear and avoidance. The CER may also be strengthened if the patient’s thought of the dentist elicits a strong emotional response. There are many other factors that play a role in determining the strength of the conditioned emotional response. They can include:

- attitude of the staff personality traits of the patient as well as the practitioner.

- the manner in which the patient perceives the dentist, the accuracy of that perception, as well as other factors that will be examined as common determinants of dental fear and anxiety.

THE APPROACH–AVOIDANCE CONFLICT THEORY

This is a concept that evolves from the above explanation of simple conditioning. It explains the vicious cycle of stress and avoidance of treatment that afflict some individuals. It is a continuous cycle, magnified by past memories of trauma, negative experiences, and defensive actions developed to avoid a repetition of terrifying situations. It was first postulated in 1950 by Miller and Dollard.13 Simply expressed, an approach-avoidance conflict exists when a person has two competing tendencies—for example, one may be aware that good oral health is a necessity, and, in order to achieve this, regular dental care is required; on the other hand past dental experiences and memories of pain and discomfort cause the patient to be fearful of a reoccurrence and creates an urge to avoid another painful experience. The two competing tendencies — one to approach, one to avoid —leaves the individual in a state of conflict. The approach tendency predominates when the patient makes an appointment with the dentist some weeks in the future. However, as the appointment time nears and the thoughts of past traumatic experiences surface along with vicariously learned negative images of dentistry, and negative personal behavior of the dentist are recalled, fear and anxiety reign supreme, and the avoidance tendency predominates. The result is often a broken appointment, a bewildered practitioner not knowing what he or she may have done, and a large block of unused time. The practitioner needs to change this avoidance pattern by taking the time to set up an appointment solely for the purpose of consulting with the patient. The intent is to learn what went wrong and to attempt to establish rapport, trust, and a positive cycle of treatment once again. This is the time to examine, discuss, and evaluate. Each participant can evaluate the other, without the presence of impending treatment or fee. A dental practitioner can improve rapport and trust by expressing concern and encouraging a patient’s positive awareness and desire for a well cared-for dentition. Often when the practitioner fails in creating a positive patient-dentist relationship and lacks a total understanding of his or her patient, a mid-treatment crisis is invited, and a time-out is needed. Such changes may be just what is needed to lower the avoidance level. I believe this is one of the first important steps a practitioner can take in beginning to recognize and understand how to lessen fear and promote mutual understanding.

Clinical chairside consideration

Learn to recognize warning signs and become aware of reasons for

- developing negative behaviors;

- lack of trust;

- frequent questioning;

- increased criticism of ongoing treatment; and

- apparent dissatisfaction.

When they appear the practitioner must reestablish a positive and caring cycle of treatment by pausing to determine the reasons for this new developing patient behavior. A “time-out” is required to establish an understanding of the reasons for this developing negative behavior, pointing out to the patient the practitioner’ s awareness of this change in behavior and how that is affecting care, in a statement like “I do not know if you notice, but I sense a change in your measure of trust and understanding of what our goals were when we both undertook this particular treatment plan. Is there something I neglected to explain fully or that you do not completely understand? I suggest we pause for a moment and discuss what may be bothering you. I am sure it is a very simple thing and a moment of discussion will put you at ease and we can continue. Agreed?” (Figure 2.1).

Chairside implications

- Failure to recognize the hidden signs of unrealistic demands/expectations or subtle signs of possible emotional and psychological disorders due to incomplete pre treatment history gathering, combined with a lack of knowledge of behavioral modalities to manage them, invites potential failure.

EXPLORING THE LITERATURE CATALOGING THE COMMON FINDINGS OF EACH OF THE DETERMINANTS OF DENTAL FEAR

Pain-related fear and anxiety is an everyday reality within the dental office. There are many stimuli within the dental environment that can act to trigger fear of pain, such as the sound of the drill or the sight of dental instruments, the needle and the dentist. Fear is also influenced by thoughts of past negative and aversive experiences, as well as a host of physical, psychological, emotional, and sociodemographic factors that predispose individuals to experience pain.14,15 Fear of pain that is associated with dental treatment has been identified as a major element of dental anxiety, and the anticipation of that pain a major obstacle to seeking treatment.2,16–19

Figure 2.1 Chairside model to eliminate fear–one to ameliorate fear, the other to maintain and enhance the negative effect of it.

Pain has been described in the literature in 1967 by Mersky and Spear20 as “an unpleasant experience which we primarily associate with tissue damage or describe it in terms of tissue damage or both.” In 1979, the definition was modified by an international group of pain experts to include “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.” 21 These definitions seem to imply that the presence of pain means an individual is having a negative or aversive experience that is related to or is perceived to being related to body damage. Dworkin22 broadens the definition of pain to “that which the individual decides hurts.” The key words in this definition are:

(1) the individual, implying long + term developmental, personality, or character logical traits of the patient that combine to contribute to the patient’s current fear related pain behavior.

(2) Decides refers to momentary and additional immediate factors that determine the current state of the individual, leading to a decision either to report or to withhold a pain response.

(3) Hurts suggest a quality and quantity of the sensation perceived as and responded to as pain, including its duration, location, and nature.

This definition by Dworkin expresses what the average dental practitioner seems to wonder about when his or her patient says “it hurts” or “I put off coming because I fear the pain that I expect is part and parcel of the cure.” What factors, either physiological or psychosocial, are responsible and are in play at this moment, that have produced this negative feeling of pain and/or anticipation of it? What can I, the practitioner, do now and in the future to both anticipate and prevent this barrier to dental care? This is what has so often filled my chairside thoughts as well many others dentists, I am sure.

Several concepts have been suggested to explain fear and anxiety related pain in dentistry. Mower’ s two-factor theory, developed in 193923 and modified by Milgrom and Weinstein in 1985,10 explains how a patient develops a conditioned emotional response to a particular dental stimulus such as the sound of the drill, and learns to avoid and strengthen that response by avoiding encounters with the initial dental stimulus. Davey’ s model24,25 presents a wider and more diverse approach to the learning of fear of pain. It has a twofold explanation in which dental events may inhibit or prevent future fear of pain. Another model is called “latent inhibition,” which states that if an individual experiences many years of treatment without experiencing a negative event, the many positive experiences may moderate a conditioned response, such as pain. The positive relationship developed over the years is too strong to permit a strong emotional response by another unconditioned stimulus, such as cut lip, the result of the drill slipping. A third model, or “the expectancy model,” put forth by Reiss and McNally26 in 1985, and is founded on two components to fear. One is that expectations of loss of emotional control happen in certain situations, and the other is anxiety sensitivity, a belief that these expected experiences pose a danger and are threatening. Combined, these two components act to influence the behavioral response, especially the avoidance factor. A more detailed view of these three concepts may be found in Mostofsky, Forgione, and Giddon’ s Behavioral Dentistry.27

Anxiety sensitivity – a predictor of pain-related fear

Anxiety sensitivity refers to the presence or absence of fear and anxiety-related symptoms and the belief that these symptoms possess negative somatic or psychosocial consequences. It represents a psychological dimension that serves to intensify the anxious and fearful response to potentially anxiety-evoking stimuli. For example, if an individual perceives that certain aroused bodily feelings are signs of a potential threat or harm, this heightened state of anxiety sensitivity will be likely to result in increased degrees of anxiety. If the individual lacks a method of coping or control, he or she may be at risk of panic.28 This could result in avoidance of the perceived potential threat.

Predictability and controllability are believed to be critical components in the development and continuation of fear and anxiety, with unpredictability being associated with heightened levels of anxious and fearful responses. Being able to predict negative events and situations in the dental environment has been recognized as a central means in determining the development and maintenance of an individual’ s level of susceptibility to fear, anxiety, and panic regarding dental treatment, according to Zvolensky et al.29 Asmundson30 hypothesized in 1999 that anxiety sensitivity may increase the risk of developing high levels of pain-related fear, because many individuals may be more likely to fear the painful consequences associated with dental care. Several studies have evaluated anxiety sensitivity as a predictor of pain-related fear and anxiety, but it is not within the scope of this text to detail each study, though I shall list some of them.31–37 Overall, these findings reiterate the importance of anxiety sensitivity in understanding pain-related fear and anxiety. They suggest that anxious and fearful response levels can be predicted with greater accuracy when more information is available about the anxiety sensitivity causing event, such as the patient not knowing how long anesthesia will last during an extraction, the time involved in a crown preparation, or the length a particular procedure may last. This lack of information could result in increased anxiety sensitivity and subsequent increased levels of pain response and avoidance.

Common findings in the literature suggest a direct relationship between:

- predictable levels of anxiety sensitivity;

- the amount and quality of treatment information provided; and

- the manner in which it affects the patient’s perception and response to the anticipated threat.

In 2002, Maggirias and Locker38 suggested that pain was more likely to be reported by those with prior fear-related painful experiences; furthermore, those who were anxious about dental treatment expected treatment to be painful and thought they had little control over treatment. They suggested that pain and fear-related response to pain are as much a cognitive and emotional construct as a physiological experience. These cognitive processes responsible for generating and maintaining these beliefs must be considered, as well as the sensory pain experiences that occur during treatment. Also, subjects who feel they have no control over what happens during treatment are more likely to report pain and pain-related fear. Maggirias and Locker also theorized that some individuals are more successful in conveying their concerns regarding fear of pain and pain itself to their dentist, thus enabling the dentist to modify his or her clinical or interpersonal approach to minimize the possibility of pain or the perception of pain. In 2006, a study by Klages et al. found that dentally fearful patients disposed to high anxiety sensitivity amplify pain anticipations when exposed to a stressful situation, such as dental treatment, and, furthermore, that when dentally fearful individuals are undergoing dental treatment, their beliefs about negative bodily arousal may negatively influence their cognitive evaluation of treatment related pain.39 Therefore, providing pretreatment information might help lessen the negative anticipation individuals have of fear-related pain.

Common findings in the literature

- Patients should be encouraged to express their concerns regarding pain.

- Dentists should be encouraged to respond and modify their clinical and behavioral approaches to meet the immediate needs and goals of the patient.

- Improved patient-dentist communication will reduce anxiety sensitivity and transfer some degree of control to the patient.

This suggests that the dentist has the ability to influence the patient’s perception of pain by the use of interpersonal and behavioral strategies. Various studies support this approach.40–43

Clinical chairside implications

- Increased information = enhances predictability = decreased fear = lessened pain response.

- Uninformed patients = unpredictability = heightened levels of anxiety and fear = failed/missed appointments = uncompleted treatment.

A well-informed patient, more knowledgeable about what is to be done, how it will feel, and how long the event will take, can better cognitively appraise the potential threat and formulate different methods to cope emotionally with the negative experience. However, the interpretation of situations and information will vary from individual to individual, so practitioners will have to determine whether more or less information will be beneficial.

The second component that determines the level of anxiety sensitivity and therefore the level of fear-related response is whether or not the individual has or perceives the ability to control the present event. In truth, while patients are in the dental chair undergoing a given procedure, real control is always in the hands of the dental practitioner but it is the degree of control that a patient perceives he or she has over the impending dental treatment that determines the level of anxiety sensitivity and therefore the level of fear related discomfort or stress. Patients benefit from a combination of knowing what, why and how a procedure will be done as well as how it will feel. When this occurs, they are more likely to avoid anticipation of the unexpected, and are better able to predict what will occur. This provides the patient with a perception of control, which Feldner and Hekmat44 have shown to exert a direct influence on pain tolerance and its endurance. Control exercises a direct influence on the cognitive appraisal of any potential threat, giving credence to the theory that if one can help a patient perceive a degree of control during treatment, then autonomic body arousal might be lessened when a painful stimulus is encountered.

Patients with a high desire for control are usually associated with Type A behavior, higher education levels, and stronger achievement behavior; they come to the dental appointment with low felt control, expecting greater pain and distress than do other patients. Increasing such an individual’s perceived control can result in lower levels of pain within this subgroup.

In the presence of aversive stimuli such as the drill or dental needle, the difference between perceiving control and feeling an inadequate level of control puts patients at risk for negative experiences. That difference can exacerbate aversive reactions during stressful dental procedures. Practitioner who provides control-enhancing coping strategies can be particularly effective in lessening the fearful response.45 This greatly improves the ability of the dentist and the patient to develop specialized coping strategies, should they be required.

Still, it is important to remember that not all patients will need to have control within the dental setting. Some people believe that whatever life’s events confront them, they are governed by external forces outside of their ability to control and therefore are resigned to accept whatever negative experiences might confront them, such as the pain of dental treatment. Individual past experiences, and individual differences in physiology and sensitivity to pain, will also influence the specific appraisal of dental treatment as threatening, and therefore play a role in affecting pretreatment anxiety sensitivity.

Common findings in the literature

There are two dimensions to patient’s dental stress:

- desired control

- perceived control(actual felt control) during dental procedures.

The greater the difference between high desire for control and actual felt control perceived, the greater likelihood of a perception of harm and distress by the patient, leading to greater aversive responses during treatment. Desired control may reflect the patient’s level of threat, whereas felt control is a reflection of the patient’s ability and confidence in his or her individual coping skills. The ability of the individual to utilize coping strategies may be a predictor of the levels of fear and avoidance that will accompany that patient during treatment.

Clinical chairside implications

Autonomic bodily arousal and heightened anticipation of pain-related fear can be lessened by:

- strategies and coping modalities that permit increased perception of felt control by the individual during dental treatment.

- It is the dental practitioner’s responsibility to acquire these skills.

GENDER, AGE, SOCIOECONOMIC, LIFE STATUS DETERMINANTS OF DENTAL FEAR

Gender and age

Gender and age are two of the most commonly reported factors in the literature that are associated with differences in levels of dental fear in response to dental care.46–50 Gender and age have frequently demonstrated a relationship with dental fear and anxiety, which more frequently reported in females than males. In 2007, Heft et al.51 found women were more likely to report general dental fear and general fear of dental related pain more than men, but men and women did not differ in their willingness to express their fearful feelings. However, regarding the fear of treatment or a particular aversive dental stimulus associated with dentistry, both men and women preferred using a more socially acceptable term like “dread,” rather than words like frightened or fearful. Eli et al.52 concluded in 2000 that females remembered more pain after treatment than males, while Locker53 reported in 2003 that women often reported more negative dental experiences than males.

Gender, age, dental fear and anxiety ar/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses