Careers in Public Health for the Dental Hygienist

Sharon Logue, RDH, MPH and Kathy Voigt Geurink, RDH, MA

Upon completion of this chapter, the student will be able to:

• Explain public health career options for dental hygienists.

• Discuss public health careers as a means of addressing the problem of access to oral health care.

• Define the mid-level provider role in addressing access to oral health care.

• Define skills and educational requirements for various roles in public health.

• Explain the relationship of private practice activities to public health activities.

• Identify specific careers, categorized by the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA)-designated roles of the dental hygienist.

Opening Statements

Career Possibilities

• Public health hygienist at a local health department

• Statewide coordinator for a school-based fluoride varnish program

• Dental hygienist at a Veterans Affairs hospital

• Dental hygienist working with a state migrant farm worker program

• Dental hygienist at a state correctional facility

• State dental director in a state health department

• Dental hygienist with a university hospital department

• Dental health educator with a school system

• Dental hygienist on a dental sealant team

• Dental hygienist in the US Public Health Service (PHS)

• Dental hygienist contracting for service in a nursing home

Community Oral Health Practice as A Career

Dr. Alfred Fones is credited with initiating the development of the profession of dental hygiene and establishing the public health career for dental hygienists. In 1906, he trained the first dental hygienist, Irene Newman, and in 1913, he started the Fones School of Dental Hygiene in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Dr. Fones developed a curriculum for dental hygienists who began work within the Bridgeport Public School system. The first dental hygienists were trained to work in the community providing education and preventive services in their role as an advocate for dental public health.1

Future Trends for Dental Hygienists in Public Health

The Problem of Access to Oral Health Care

In a national report entitled Oral Health in America, the Surgeon General reviewed the profound disparities among specific population groups in oral health status and access to dental care.2 Dental disease is a chronic problem among low-income populations.3 Federal agencies and state governments are addressing these gaps in access to oral health care through legislation and policy development. Examples of some actions created through these processes are shown in the Guiding Principles box.3,4 At the 2009 Access to Dental Care Summit, the American Dental Association (ADA) listed expansion and distribution of a well trained workforce with nationwide evaluation, standards, and regulations as a long-term strategy in improving access to dental care for underserved populations. Under this heading, the mid-level provider in dentistry was discussed and models are being developed and reviewed.5 Summits and conferences on access such as this and the follow-up strategies and action plans will very likely increase the demand for dental hygienists working in community oral health practice.

Alternative Practice Settings

Public health settings are categorized as alternative practice settings (i.e., providing oral hygiene services outside the private office in a “nontraditional” setting). Examples of the setting might be a community clinic, a mobile van, a school, a hospital, or a nursing home (Figures 2-1 and 2-2). The delivery of dental services offered in private practice does not reflect the need for services for those without means or without the capability of accessing care. In an alternative setting, dental care can be brought to people in need. Dental hygienists can provide preventive services in these settings, reaching large numbers of people who might not otherwise receive care.

Preventive services, or primary prevention, are more effective, less costly, and involve less technology than secondary or tertiary prevention (Box 2-1). Methods such as fluoride varnish or sealant programs, nutritional counseling, dental health education to community groups, and oral hygiene services and instruction are at the primary level. Often primary prevention strategies do not require a dentist.6 Therefore, with less restrictive supervision, the dental hygienist can perform functions at this level and reach underserved populations.

Public Health Supervision

Regulatory Changes

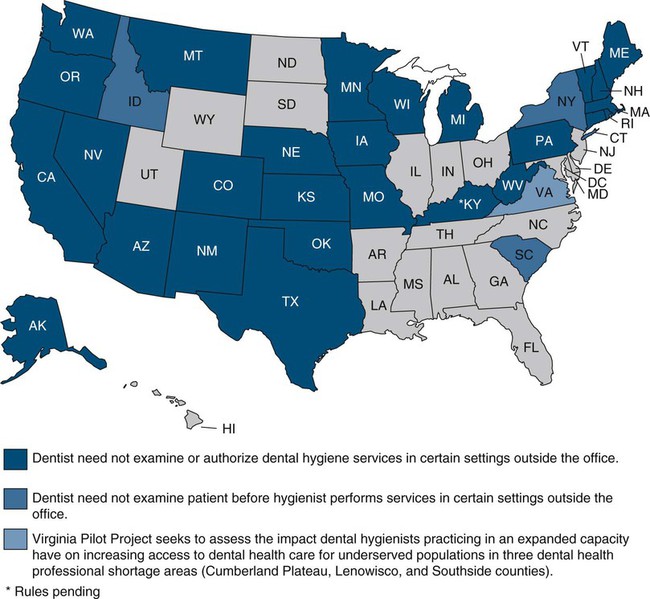

Because of the need for services in places such as schools, nursing homes, and migrant health centers, dental hygienists are initiating oral health programs in these alternative settings. They are also filling positions beyond those connected with public health agencies. To create such positions, dental hygiene regulatory changes are being discussed and are under way throughout the United States. As a solution to the access problem, many states have changed restrictive dental practice acts that prevent the dental hygienist from practicing without the supervision of a dentist and that prevent dental hygienists from receiving direct reimbursement form third-party payers such as Medicaid or private dental insurers. To view which states allow direct access to care without the need for a dentist to examine or authorize the dental hygiene services see the map in Figure 2-3. To determine supervision levels for specific dental hygiene services by state, view the website www.adha.org/governmental_affairs/practice_issues.htm. Examples of changes in state regulations around the scope of practice for dental hygienists include New Mexico, where dental hygienists are allowed to practice in certain settings without the oversight of a dentist through a collaborative practice agreement with a dentist or group of consulting dentists, and Washington state, where dental hygienists may practice unsupervised in hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies, group homes, state institutions, and public health facilities provided the hygienists refers to the dentist for treatment and meets a requirement of clinical experience. Colorado is one of the states that allows dental hygienists to practice without supervision in all settings and allows licensed dental hygienists to own a dental hygiene practice. In a 2001 ADHA Access to Care Position Paper, the ADHA confirmed its position that dental hygienists who are graduates from an accredited dental hygiene program can be fully used in all public and private practice settings to deliver preventive and therapeutic oral health care safely and effectively. “Licensed dental hygienists, by virtue of their comprehensive education and clinical preparation, are well prepared to deliver preventive oral health care services to the public, safely and effectively, independent of dental supervision.”7

1. The ratio of dentists to people

2. The number of dentists and dental hygienists in the state

3. The number of low-income adults and children who need dental care

These factors contribute to defining dental health professional shortage areas. Statistics compiled from Synopsis of State and Territorial Dental Health Programs provide information necessary in determining the available workforce of dental professionals and of community health departments and clinics.8 The workforce numbers, compared with population size, are useful in determining professional shortage areas and the need for community oral health programs. Inadequate access to health care caused by professional shortages and geographic and financial barriers prevents people from attaining improved health status and improved quality of life. The dental profession, in realizing the need for reaching these underserved populations, is initiating preventive programs conducted by dental hygienists in many states.

Mid-Level Provider

In the medical field, a mid-level provider is the term for a clinical medical professional who provides patient care under the supervision of a physician. Examples of mid-level providers include the nurse practitioner and the physician assistant. These professionals have advanced medical training but not on the level of the physician. It has been reported that physician assistants and nurse practitioners provide a majority of physician services for a much lower cost than the physician, thereby addressing the unmet need for medical services by providing quality care to more people at a lower cost. This concept applied to dentistry also addresses the problems of access to oral health care for underserved populations. Various models of workforce delivery are being developed to serve the populations who cannot easily access dental services as the result of problems of geographic location, poor financial resources, no dental insurance, and a lack of understanding about disease prevention measures. A shortage of dentists to meet the needs of the population and low dentist participation in Medicaid programs also affects access. The burden of oral disease is spread unevenly throughout the population (see Chapter 6), with minority children from low income families and the elderly population being most vulnerable. Models of delivery are provided in the next section, including the advanced dental hygiene practitioner (ADHP) defined in Chapter 1. Dental hygienists should develop an understanding of the necessity for new provider types in the existing health care system.

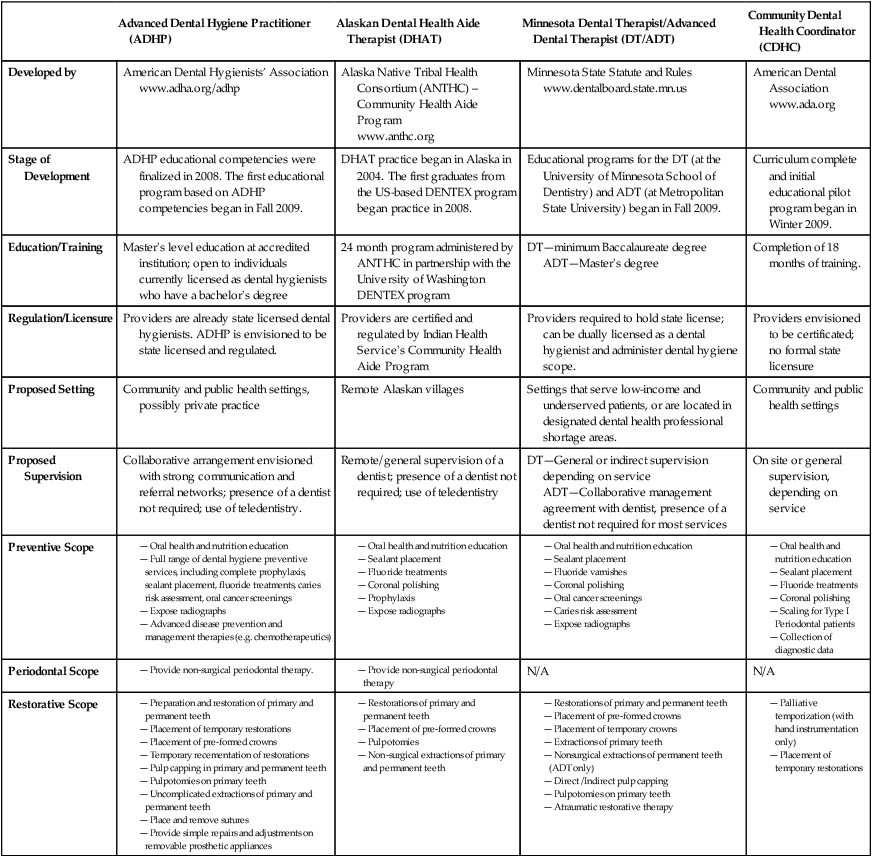

Community Dental Health Coordinator

In 2006, the ADA proposed the development of the community dental health coordinator (CDHC) to support the existing dental workforce in reaching out to underserved communities.9 The CDHC works under the supervision of the dentist to promote oral health for communities and to assist patients in navigating through the health care system to establish a dental home. They would complete a 12-month training program and 6-month internship.

Advanced Dental Hygiene Practitioner

In June 2004, the ADHA House of Delegates, addressing the problem of access to health care, approved the creation of the ADHP credential. As stated in Chapter 1, this credential allows dental hygienists to provide diagnostic, preventive, restorative, and therapeutic services directly to the public.9 Dental hygienists who receive the ADHP credential have graduated from an accredited dental hygiene program and also have completed an ADHA-approved advanced educational curriculum. This credential is designed to improve and enhance the oral health care delivery system. Because dental hygienists with the ADHP credential do not have to be supervised by a dentist, the door will open for them to work in school systems and nursing homes, as well as with underserved populations throughout the country.

Minnesota Dental Therapist and Advanced Dental Therapist10

The effort to establish a mid-level oral health provider went through a legislative process in Minnesota in 2008–2009. The result was the establishment of dental therapist (DT) and advanced dental therapist (ADT) programs. ADT trained at the University of Minnesota can provide basic preventive services, limited restorative services, extractions of primary teeth, and have limited prescriptive authority. A dentist is required to be present for the more complicated procedures, such as restorative procedures and extractions, but not required to be on site for preventive services. In the fall of 2009, the first dental hygienists entered a Master’s program at Metropolitan State University based on the ADHP competencies developed by the ADHA. Graduation from this program provides the dental hygienist with a master’s degree and the ADT title. The ADT will evaluate, assess, and plan treatment; perform nonsurgical extractions of permanent teeth; and administer all services of a DT without the requirement of onsite supervision. An ADT can also work in a collaborative management agreement with the dentist. The ADHA website (www.adha.org/governmental_affairs) posts the most current state legislative news on the ADHP and the DT and ADT programs, as well as other related legislative processes.

Table 2-1 describes the oral health current and proposed providers. See Additional Resources for more information on the oral health care workforce.

Table 2-1

Oral Health Care Workforce—Current and Proposed Providers

| Advanced Dental Hygiene Practitioner (ADHP) | Alaskan Dental Health Aide Therapist (DHAT) | Minnesota Dental Therapist/Advanced Dental Therapist (DT/ADT) | Community Dental Health Coordinator (CDHC) | |

| Developed by | American Dental Hygienists’ Association www.adha.org/adhp |

Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC) – Community Health Aide Program www.anthc.org |

Minnesota State Statute and Rules www.dentalboard.state.mn.us |

American Dental Association www.ada.org |

| Stage of Development | ADHP educational competencies were finalized in 2008. The first educational program based on ADHP competencies began in Fall 2009. | DHAT practice began in Alaska in 2004. The first graduates from the US-based DENTEX program began practice in 2008. | Educational programs for the DT (at the University of Minnesota School of Dentistry) and ADT (at Metropolitan State University) began in Fall 2009. | Curriculum complete and initial educational pilot program began in Winter 2009. |

| Education/Training | Master’s level education at accredited institution; open to individuals currently licensed as dental hygienists who have a bachelor’s degree | 24 month program administered by ANTHC in partnership with the University of Washington DENTEX program | DT—minimum Baccalaureate degree ADT—Master’s degree |

Completion of 18 months of training. |

| Regulation/Licensure | Providers are already state licensed dental hygienists. ADHP is envisioned to be state licensed and regulated. | Providers are certified and regulated by Indian Health Service’s Community Health Aide Program | Providers required to hold state license; can be dually licensed as a dental hygienist and administer dental hygiene scope. | Providers envisioned to be certificated; no formal state licensure |

| Proposed Setting | Community and public health settings, possibly private practice | Remote Alaskan villages | Settings that serve low-income and underserved patients, or are located in designated dental health professional shortage areas. | Community and public health settings |

| Proposed Supervision | Collaborative arrangement envisioned with strong communication and referral networks; presence of a dentist not required; use of teledentistry. | Remote/general supervision of a dentist; presence of a dentist not required; use of teledentistry | DT—General or indirect supervision depending on service ADT—Collaborative management agreement with dentist, presence of a dentist not required for most services |

On site or general supervision, depending on service |

| Preventive Scope |

— Preparation and restoration of primary and permanent teeth

— Placement of temporary restorations

— Placement of pre-formed crowns

— Temporary recementation of restorations

— Pulp capping in primary and permanent teeth

— Pulpotomies on primary teeth

— Uncomplicated extractions of primary and permanent teeth

— Provide simple repairs and adjustments on removable prosthetic appliances

Careers in Public Health

Dental hygienists in public health positions use a variety of skills in implementing community oral health programs that have positive effects on their communities. In this chapter, the roles of the dental hygienist are further defined as they apply to specific career options (Figure 2-4). The ADHA has designated five dental hygiene roles, and public health is a component of each. Most public health jobs require a combination of skills defined in these multiple roles. Positions held by dental hygienists working in public health are included to inspire and illustrate the variety of career possibilities.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses