17 Surgery of the temporomandibular joint

ASSUMED KNOWLEDGE

It is assumed that at this stage you will have knowledge/competencies in the following areas:

INTENDED LEARNING OUTCOMES

At the end of this chapter you should be able to:

MINIMALLY INVASIVE TECHNIQUES

Injection into the joint

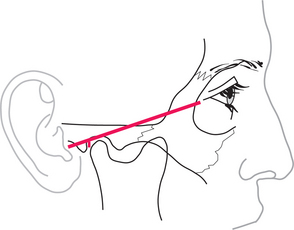

The upper joint space is most easily approached from below and behind, starting from a point 10 mm in front of the point of the tragus, just below a line that joins that point to the outer canthus (Fig. 17.1). With the mouth open, or the mandible protruded, the needle is inserted upwards, forwards and medially, until it penetrates the capsule just above and behind the condyle; this may be as deep as 2 cm from the surface. To check that the needle is in the joint, a small quantity of saline is injected then drawn back. It should be readily possible to flush fluid in and out of the joint. If no fluid can be withdrawn, the tip of the needle is unlikely to be in the joint and the position should be reassessed and adjusted. The average joint may be distended with about 2 mL of fluid.

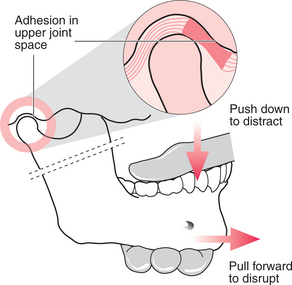

Closed manipulation for adhesions: method and results

It is important, after the local anaesthetic has been placed, to measure the mouth opening, in order later to be able to determine the change that has taken place. The operator stands beside the patient, who is seated and leaning slightly backwards. The operator holds the mandible, with the thumb from the opposite hand inside the patient’s mouth, resting on the posterior teeth and the fingers placed beneath the body of the mandible (Fig. 17.2). The patient’s head is held fast against the operator’s body with the other hand, the fingers of which are placed over the TMJ to feel any movement within it. The thumb is used to push down on the posterior teeth and distract the joint, then slowly the mandible is drawn forwards with increasing force until increased mobility is achieved. This often happens as one or two sudden releases. When maximum movement is achieved, mouth opening should be measured again.

It is often possible to gain considerable mobility in closed lock by this technique. Unfortunately it can result in considerable pain over the following few days, leading to the patient moving their jaw little and the consequent reforming of adhesions. This effect can be reduced by giving NSAIDs before and after the treatment, but a considerable inflammatory exudate still remains within the joint. The pain and immobility can be eased further by irrigating the joint with saline and instilling a small quantity of steroid (see pp. 242, 245).

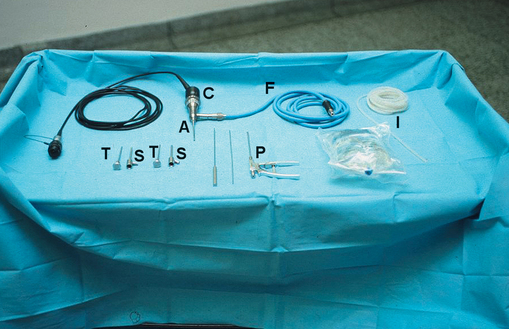

Arthroscopy

An arthroscope is an endoscope designed specifically for use within a joint (Fig. 17.3). TMJ arthroscopes are up to 2.8 mm in diameter and rigid. With these devices it is possible to inspect the whole of the upper joint space without formally dissecting the joint, all through a skin puncture a few millimetres in diameter.

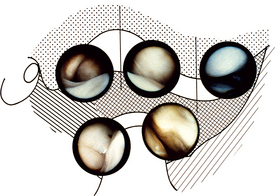

The joint can be examined by direct vision, but it is more common to attach a video camera to the scope and to display what is seen on a television monitor (Fig. 17.4).

With the simplest of equipment the joint can be inspected, usually starting with the posterior recess, looking at the position of the disc, the condition of the posterior attachment tissues and the synovium on the medial aspect of the joint. The scope is then swept anteriorly over the top of the disc to look at the anterior parts of the joint. By inspection alone it is possible to detect disc displacement, adhesions, degenerative changes in the disc and cartilage over the glenoid fossa and articular eminence and synovial inflammation. It is possible, if adhesions are detected, to replace the blunt-ended trocar and sweep around within the joint to break them down. The joint must be thoroughly irrigated at the end of the procedure and many surgeons will finally instil a steroid before leaving the joint. It is often necessary to place one suture in the skin wound.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses