Chapter 14

Diagnosis of pulpal and periapical disease

Introduction

From textbooks, students normally learn about diagnosis through studying the traits of various diseases. Expected symptoms, signs and test results of, for example, pulpal inflammation, are presented, the diseases are given and their clinical, radiographic and laboratory expressions discussed. However, such a learning procedure is the reverse of what happens in the clinical situation. Patients rarely know what they suffer from. Instead they present with certain symptoms, signs and test results. While suspicions often can be raised in several directions, the task of the clinician is to carefully weigh the collected information to find the right signal or diagnosis. This chapter therefore will start with a discussion on how diagnostic information may be evaluated before the specific measures that may be taken to identify the endodontic disease conditions are reviewed.

Evaluation of diagnostic information

Making the right diagnosis is often a complex task and clinicians may easily arrive at different conclusions. Many studies have demonstrated how physicians and dentists vary in the way they practice their profession, regardless of whether they are defining a disease, making a diagnosis or selecting a therapeutic procedure. For example, in a study on microscopic investigation of biopsy specimens from the uterine cervix, 13 pathologists were asked to read 1001 specimens and to repeat the readings at a later point in time. On average, each pathologist agreed with him or herself only 89% of the time (intraobserver agreement) and with a panel of “senior” pathologists only 87% of the time (interobserver agreement). Looking only at patients who actually had cervical pathology, the intraobserver agreement was only 68% and the interobserver agreement was 51% (34).

Many similar studies on various signs and symptoms have been carried out and the literature on observer variation has been growing for a long time (8) (Key literature 14.1). From a diagnostic point of view it has been found that, in general, observers looking at the same attribute will disagree with each other or even with themselves 10–50% of the time (10). Many authors have regarded the diagnostic process more as an act of art than of science: “Traditionally, the process of diagnosis was left undefined, a natural art, or explained as a process of intuition. Despite recent advances, this is still too often the case” (12). In Dorland’s Medical Dictionary (7) “diagnosis” is defined as “The art of distinguishing one disease from another”. During recent years clinical reasoning has been the subject of substantial research, and both descriptive and normative models have been proposed (22).

Diagnostic accuracy

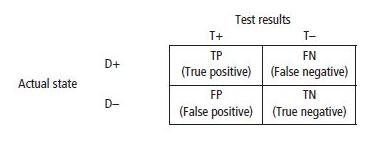

Let us assume that the question of whether or not a patient has a certain disease D in a clinical situation can be determined only by a test T. It is possible to obtain two test results: one indicating that the patient has D (a positive test, T+) and one suggesting that the patient does not have D (a negative test, T–) (see Core concept 14.1). Unfortunately, T has the drawback (which it shares with almost all tests and procedures) that it cannot completely separate persons who have D and those who have not. Two types of error are then possible. A person who has D can be informed that he or she has not (a false-negative diagnosis) and another person can receive positive test although he or she does not have D (a false-positive diagnosis). Of course there are also two types of correct outcomes of the test: true-positive and true-negative diagnoses, respectively. The proportions of these four possible outcomes can be used to express the diagnostic value attached to the test. Sensitivity – or the true-positive ratio – is a measure of the proportion of patients with D correctly identified as positive. Specificity – the true-negative ratio – is a measure of the proportion of persons without D correctly identified as negative. In order to determine the sensitivity and specificity of a diagnostic test a comparison with some sort of ideal “gold standard” has to be made. There must be some test-independent way of making a definitive diagnosis of whether the patient is diseased or not. Preferably, such a gold standard is created by means of a biopsy, but often another test normally not clinically available because of high costs or severe adverse effects may serve this purpose. In most cases investigators have to use gold standards that are below “24 carats”.

| T+ | = | positive test result |

| T– | = | negative test result |

| D+ | = | disease present |

| D– | = | disease absent |

In the clinical situation the most interesting questions are formulated in a slightly different way. When the test indicates that the patient is diseased (T+), what is the probability that he or she really has D? And if the patient gets a negative result (T–), what is the probability that D is not present? These probabilities are given in the so-called positive predictive value (PPV) and the negative predictive value (NPV). In contrast to sensitivity and specificity, PPV and NPV are dependent on the prevalence of the disease. Let us assume that a test has 90% sensitivity and 95% specificity for a certain disease. If the prevalence of the disease is 50%, then the PPV will reach 95%. This means that if a patient receives a positive result there is 95% probability that he or she is diseased. If the prevalence is 10%, the PPV will decrease to 67%; if the prevalence is 1%, the PPV is only 15%. This mathematical exercise tells us that tests do not work well when prevalences are low. Accordingly, in a clinical situation, tests should not be used on a routine basis. By history taking and oral examination the clinician selects patients in which a specific test may be used. What he or she actually does is to increase the prevalence of the suspected disease!

Receiver operating characteristic analysis

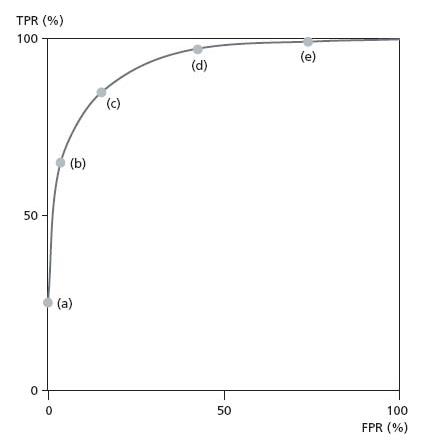

If rates of true-positive response (TPR) and false-positive response (FPR) are calculated for different decision criteria (cut-offs), the obtained pairs of values may be plotted in a simple graph with the TPR placed vertically and the FPR horizontally. Various cut-off points may be obtained in many ways. For example, in radiographic diagnosis of periapical lesions the level of confidence of the observer often is used. Both the TPR and the FPR are calculated for five decision critera: definitely a lesion; probably a lesion; uncertain; probably no lesion; definitely no lesion. The plotted points form what is called the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (Fig. 14.1).

The position of the ROC curve will tell us how good a test is at discriminating between people (or teeth) who have the disease from those who do not. The ROC curve of the perfect test coincides with the axes, whereas the curve of the worthless test lies along the 45° diagonal. We can measure the discriminatory power of a test by how close its ROC curve is to the axes and how far it is from the diagonal. More precisely, the discriminatory power is measured by the area under the curve, which is 100% for the perfect test and 50% for the worthless test. An ROC analysis demonstrates that changing the cut-off point will not influence the discriminatory power of a test, it just moves its position along the curve. However, different cut-off points can have momentous clinical consequences for those affected by the judgment, and a strategy for deciding the position to be taken on the curve must be developed (see next section).

Fig. 14.1 In radiographic diagnosis of periapical lesions, true-positive rates (TPR) and false-positive rates (FPR) can be calculated for five decision criteria: (a) definitely a lesion, (b) lesion probable, (c) lesion uncertain, (d) probably no lesion, (e) definitely no lesion.

Receiver operating characteristic analysis of periapical radiography

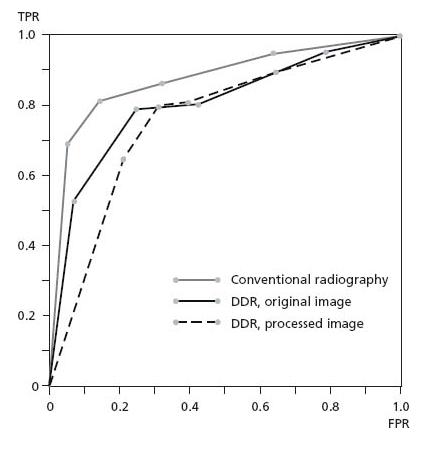

In a study by Kullendorff et al. (23) the aim was to compare the observer performance of direct digital radiography, with and without image processing, with that of conventional radiography, for the detection of periapical bone lesions. For 50 patients a conventional periapical radiograph using E-speed film was taken and then a direct digital image of the same area was made. The images of 59 roots were assessed by seven observers using a five-point confidence scale: definitely no lesion; probably no lesion; uncertain; probably a lesion; definitely a lesion. A gold standard was created by independent readings of 73 films by two experienced radiologists. Only images where they agreed (totalling 59) were included in the study. ROC curves were established and mean values of the observers’ decisions are shown in Fig. 14.2.

Fig. 14.2 ROC analysis of periapical radiography showing observer decisions for 59 radiographs (23).

Conventional film radiography came out slightly better from the study than direct digital radiography. Image processing did not improve the observer performance.

Diagnostic strategy

The diagnosis is not a goal in itself but only, in the words of a Scottish clinician, “a mental resting-place” for prognostic deliberation and therapeutic decisions (45). One of the main concerns for this deliberation is of course the fact that no diagnostic method has perfect sensitivity and specificity, which means that false diagnoses cannot be avoided completely. Also, from ROC analysis we learn that diagnostic decisions always have “costs”. If we want to be sure that all cases treated are really diseased, we have to take a low position on the ROC curve. The cost for this will be a number of missed cases. In contrast, if we want to treat all diseased patients (or teeth), a high position on the ROC curve is needed and the cost will be a number of healthy cases being treated. If an analysis of an actual clinical situation results in a strategic decision to avoid overtreatment (low ROC position), then the clinician should signal for disease only when he or she is absolutely certain that it is present. If the problem is to avoid false-negative diagnoses, the best consequences will be obtained if disease is reported at the slightest suspicion of it (high ROC position). It is important to notice that a decrease in one type of error will lead to an increase in the other.

In a situation where untreated disease will not lead to any serious complications of the patient’s general health or well-being, one normally wants to avoid overtreatment. The diagnostic process will be directed towards the avoidance of false-positive diagnoses and a low position on the ROC curve is taken. If untreated disease will lead to serious complications it is important to identify and find all or most of the diseased individuals. From a strategic point of view, false-positive diagnoses must be accepted and we have to move higher up the ROC curve.

It is obvious that if the available cure also implies great risk of severe complications or serious adverse effects, one does not want to perform any unnecessary treatments. The price to pay for accepting false-positive diagnoses will then be too high. In contrast, the diagnostic position should be moved higher up the ROC curve if treatment is simple and without any considerable risk.

All medical and dental care is associated with economic costs and thus resources must be regarded as limited. Diagnosis and treatment have to be cost-effective and if the available therapy is very expensive one does not want to start a treatment on a false-positive diagnosis. For example, if a crown and post have to be removed in order to reach a root canal for retreatment, it is essential to be absolutely sure that this is the right thing to do. Accordingly, a lower position on the ROC curve has to be taken.

Personal values have to be included in a decision strategy. Faced with the same clinical situation, people will not evaluate the benefits and risks of a treatment procedure in identical ways. This means that the position of the diagnostic criterion has to be discussed with the individual patient. Will the patient take a false-positive diagnosis before a false-negative diagnosis, or the other way around? Attempts have been made to measure patients’ values in order to incorporate them in various decision models (38). These possibilities are discussed in more detail in Chapter 18.

Clinical manifestations of pulpal and periapical inflammation

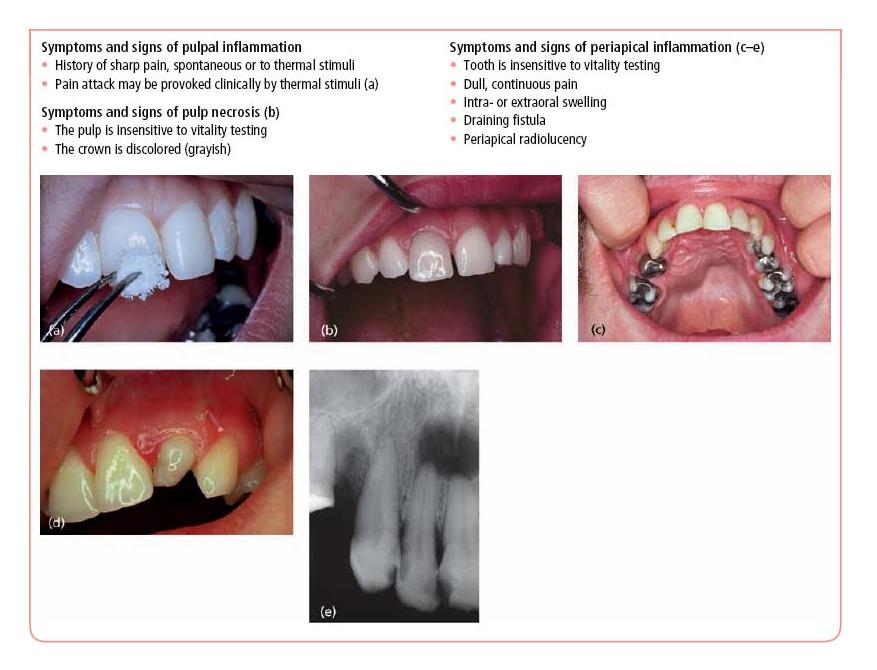

The clinical manifestations of inflammatory processes in the pulp and periapical tissues cover a broad range of expressions. Patients’ experience of dental pain may vary from a barely noticeable discomfort to an unbearable torment, from an odd pain attack of short duration to a lingering continuous suffering. Patients may, in addition, display various signs of infection, including fistulae, swellings and raised body temperature. Discolored teeth is another patient complaint that may draw a suspicion of a diseased pulp. In Core concept 14.2 the most commom symptoms and signs associated with pulpal inflammation, pulp necrosis and periapical pathosis are collected and displayed. Strangely, however, patients are usually free of symptoms and the majority of pulpal inflammations in need of endodontic treatment are revealed during operative procedures (36). In most cases. inflammatory involvement of the periapical tissues is detected only by radiographic means.

Collecting diagnostic information

Inferences regarding disease processes in the pulp and periapical tissues have to be made with the help of a rather limited diagnostic armamentarium. The main sources of information are the patient’s report on pain and other symptoms, the clinical examination of the tooth and surrounding structures, and the radiographic examination (Core concept 14.3). The problem for which the patient seeks dental care (chief complaint) is the natural point of departure for the diagnostic process. If the patient is in acute distress, the examination and diagnosis must be focused on solving that particular problem as fast as possible and a complete examination and establishment of a definitive treatment plan have to be postponed until later. A quieter situation will allow the examiner to expand on the present dental illness. The patient’s report on character, intensity, frequency, localization and external influence of the symptoms will often give clues to a tentative diagnosis. This initial notion may be strengthened or refuted by penetrating the dental history, including information on such matters as recently placed restorations, pulp cappings and potential bruxism.

When reviewing the medical history the clinician will focus on illnesses, medication and allergic reactions. Consultation with the patient’s physician is recommended when physical or mental illness is expected to interfere with diagnosis and treatment plan. There are no systemic disease conditions for which endodontic treatments are contraindicated, other than those affecting any dental procedure.

The status of the tentative diagnosis is explored further at the clinical examination. Crowns of suspected teeth are evaluated with regard to caries, defective fillings and discoloration. A fiber optic light source may be useful to disclose the presence of cracks in the enamel or dentin, and the patient may be asked to bite on a cotton roll or a firm object to confirm the diagnosis. As pointed out in Chapter 4 the true condition of the pulp is often difficult to assess but pain provocation and pulp vitality testing are helpful. Tenderness to percussion and palpation confirms a suspicion of periapical inflammation, as of course does the presence of a fistula and swelling or a periapical radiolucency in the radiograph.

- History of sharp pain, spontaneous or to thermal stimuli

- Pain attack may be provoked clinically by thermal stimuli (a)

- The pulp is insensitive to vitality testing

- The crown is discolored (grayish)

- Tooth is insensitive to vitality testing

- Dull, continuous pain

- Intra- or extraoral swelling

- Draining fistula

- Periapical radiolucency

- Anamnesis

- Clinical examination

- Radiographic examination

Some informative sources are more important than others. The following series of cases will demonstrate how pain report, pulp vitality testing and radiographic findings interact and come into play in the process of reaching a diagnosis in endodontics.

Diagnostic methodology: assessment of pulp vitality

Pulp vitality means that a given pulp has an intact neurovascular supply. Traditionally, pulp vitality has been determined by investigating response to painful stimuli. It needs to be recognized therefore that such methods test only for sensory nerve function and not necessarily for an intact pulpal blood supply. Yet, the presumption can most often be made that a tooth which responds to the provocation with a sharp pain sensation has a vital pulp. Because this is an indirect methodology the clinician has to work with hypotheses of the relation between the test result and the reality. Two main assumptions about this relation usually are made:

There are three types of pulp sensitivity tests:

- mechanical;

- thermal;

- electrical.

The guiding rules for the use of sensitivity tests are given in Core concept 14.4.

Mechanical tests

Directing a jet of compressed air and probing exposed dentin in a cavity or cervically at the neck of the tooth normally results in a sensitive reaction in a tooth with a vital pulp. Pulp sensitivity also may be evoked during drilling for removal of caries or defective fillings. In these procedures nociceptive mechanoreceptors at the pulp– dentin border are stimulated by hydrodynamic forces moving the fluid in the affected dentinal tubules (see also Chapter 3). Of course, a prerequisite for these tests is that the tooth in question has not been anesthetized. In ambiguous cases drilling a small test cavity can be useful, especially in teeth with full crown restorations. Such test cavities can also be used for thermal and electrical tests. While scientific data on the diagnostic accuracy of mechanical stimulation are lacking, it is a simple and effective means to test the status of the pulp. Indeed it is a good clinical routine in restorative procedures to postpone the administration of local anesthetics until a sensitive reaction is received from the tooth. Such a routine will prevent restoration of a tooth with a necrotic pulp.

- Explain the procedures to the patient.

- Do not rely on only one test; use combinations.

- Make comparisons with other teeth, preferably contralaterals but also with neighboring teeth.

- In cases with doubtful reactions, repeat the tests in a different order, “hiding” the suspicious to/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses