Chapter 12

Appointment Scheduling Strategies

Appointment Scheduling Policy and Philosophy

Appointment scheduling is the foundation of a dental office. All production and revenue generated by the practice result from patient fee for services. These fees result from the effective and efficient use of time. Dentistry can be described as a service business that sells time. This time is broken up into units that are used to assign patient appointments into daily scheduling. How this time is allocated and managed first depends on the number of hours available to the dental office.

The typical dental office is not open for business every day of the calendar week. Most dental offices use a 4-day workweek. In addition, by providing 7 holidays and 2 weeks of vacation each year, the average dental office may be open for production a total of 196 days per year. Most offices can count on the dental providers losing other production days due to personal or family illness or other emergencies. Time away from the office must also be allowed for professional continuing education. In large practices, time units are also lost to staff meetings and strategic planning and/or facilities maintenance. All of this means that out of a typical year (365 days), the dental office may be open for business about 50% of those days.

Since time is the most valuable product for sale in the dental practice, the best use of this resource is accomplished by establishing a scheduling policy and philosophy that allows for the effective use of this resource. The policy, along with its philosophical principles, should be written, implemented, maintained, and periodically reexamined to verify that it remains relevant within the desired context and will provide the desired results. The document should be kept in the office in a place where all the staff have access to it and can refer to it on a daily basis, as necessary. Some offices refer to this as a “recipe or system strategy” for scheduling. But whatever name is given to it, it should be a documented systematic approach to appointment scheduling that works for a particular office as long as the logic and steps are followed.

Many scheduling strategies exist among dental offices. Generally, these strategies are rooted in philosophical principles. Unless an office has scheduling principles from which an appointing strategy can be implemented, the true potential of the dental office will not be achieved. In addition, the office will not come close to receiving its highest return on investment while simultaneously providing scheduled patients with excellent care. Whoever schedules the appointments in a dental office is like the conductor of a symphony. If an appointment is not scheduled, production cannot be realized, and if appointments are not scheduled properly, office production will never reach the fullest potential. No scheduling strategy will work if there is a lack of commitment by the doctor(s) and staff. In other words, for the scheduling system to work, it must be worked. A scheduling system is worked by the consistent application of the principles involved in its management. Any decision to change the system should be decided collectively. Two of these philosophies are briefly discussed.

The first of these principles results from a relatively simple philosophy: Just keep the doctor busy and everything will work out in the end. Keep all the chairs full during office hours. Offices using this philosophy generally schedule several appointments within the same time slot just in case one or more of the patients scheduled do not show up or cancel the appointment at the last moment. The doctor, then, may also be scheduled in two or more treatment rooms at the same time. The type of treatment procedures planned for the time slot is not taken into consideration when these appointments are made. The philosophy is to just keep the doctor busy. These are the kind of scheduling philosophies found in clinics where the patients expect to wait for extended periods of time and usually only very basic types of dental treatment are provided. Another way to understand this philosophy is to view it as similar to an emergency room at a local hospital, where patients are treated on a first-come-first-served basis. This principle is to do something for each patient and to do more only if time allows.

On the other hand, some offices “orchestrate” time slot utilization. This orchestration is based on production goals, finely tuned and timed procedures (systems), disinfection and preparation time needed before and after each treatment procedure, the doctor’s time to perform each procedure, and the preferences of doctors and patients. The principles in this type of scheduling can be relatively simple or extremely complex. Some doctors prefer to schedule more complex treatment early in the day, while others prefer to schedule this treatment in the middle of the afternoon or at the end of the day. Some doctors prefer to appoint children early in the morning rather than late in the afternoon. These schedules require the complete coordination of clinical and clerical staff as well as provider staff to maintain smooth office workflow.

Either of the philosophical approaches to scheduling will work in a variety of dental settings. There are, however, many other types of scheduling that fall somewhere between these two. For the purposes of this chapter we focus on the merits and challenges involved in the principles of orchestrating an appointment scheduling system.

Types of Appointments

In order to orchestrate appointments, thought, purpose, and intent must be used to schedule all appointments before they are written in the appointment book. Appointment time increments in dental computer software are usually broken down into units of either 10 or 15 minutes. The daily appointment objective is to maintain a productive flow of patients in the practice day. Scheduling and production efficiency are critical to patient wait times. Appropriate scheduling with low no-show rates results in a most effective and efficient patientsatisfying practice. Additionally, appropriate scheduling is more likely to meet daily provider production goals. As scheduling is discussed in this chapter, consider an ideal small clinic or practice to have three chairs (operatories) and two assistants per dentist. Also consider the ideal larger practice as a six-chair (operatory) dental clinic with two dentists, four assistants, and one hygienist.

There are many strategies to developing and using scheduling blocks. Many offices have successfully used quadrant dentistry by scheduling one or two patients per hour per dentist, classifying an appointment as either exam or operative (child or adult) or emergencies (or walk-ins). Many others have used the physical operatory as the scheduling block. Some use the open access method of appointment scheduling by appointing daily call-ins and seeing call-ins the same day of the call. Some leave blank time intervals in the schedule for potential emergencies that are filled as emergencies or when new patients call in for appointment times either the same day or the next day. Providers or assistants may elect to schedule next appointments from the chair based on treatment evaluation, and suggested follow-up time intervals requiring a later reconciliation with the front desk scheduler. There are advantages and disadvantages to any strategy chosen. Provider preferences and the target market served generally dictate the best strategy for managing scheduling blocks.

Appropriate scheduling blocks and sequencing of procedures are important to the efficiency of the practice as well as to establishing patient goodwill. Time demands, scope of the treatment plan, patient requests, and treatment sequencing are aspects of scheduling that are impacted by the type of procedure provided to the patient. In other words, all aspects complement one another, and none are stand-alone considerations. Other aspects to consider along with the procedure itself include office staffing availability, provider absences, other office facilities and equipment availability, style and philosophy of the provider, and the proficiency of the dentist or provider complementing the individual need of the patient to tolerate particular treatment demands. In this section, we do not incorporate or address these aspects specifically, though we do acknowledge their existence. Instead, we refer the reader to other sections of the chapter.

Table 12.1. Ten-minute appointment book interval.

| Time Units | Dr. Zip | Dr. Dip |

| 8:00 a.m. | Ms. Happy (child exam) | Mr. Loner (emergency) |

| 8:10 a.m. | ||

| 8:20 a.m. | ||

| 8:30 a.m. | Open slot | |

| 8:40 a.m. | Open slot | |

| 8:50 a.m. | Open slot |

Table 12.2. Fifteen-minute appointment book interval.

| Time Units | Dr. Zip | Dr. Dip |

| 8:00 a.m. | Ms. Happy (child exam) | Mr. Loner (emergency) |

| 8:15 a.m. | ||

| 8:30 a.m. | Open slot | |

| 8:45 a.m. | Open slot |

Units of Time

There are many ways to utilize time to get the best production from providers and to most efficiently utilize operatories. Time units can be scheduled in 10-or 15-minute intervals. An example of a 10-minute interval appointment book is shown in Table 12.1. A 1-hour time block can comprise as many as six appointments for each of the doctors, as shown on the appointment book in Table 12.1.

An example of a 15-minute interval appointment book is shown in Table 12.2. A 1-hour time block can only comprise as many as four appointments for each of the doctors as shown.

Consideration must be given to doctor preferences and the most frequently delivered treatment procedures prior to selecting time intervals for a practice.

Operatory Availability

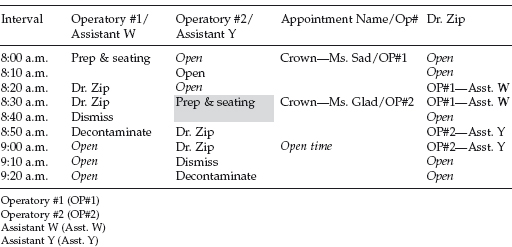

An example of a 10-minute appointment interval using operatory scheduling is shown in Table 12.3.

Operatory appointment booking allows for doctor, space, assistants, and facility use to be included in planning for the appointment. Each operatory is assigned an assistant, in this case Assistant W and Assistant Y. Some time slots shown on Table 12.3 indicate assistant functions where the doctor is not involved and present in the operatory. These may or may not be included in an actual appointment book. These slots are prep and seating, dismissal of the patient, and disinfection of the operatory. The dental assistant is primarily responsible for these required functions.

Table 12.3. Operatory appointment booking.

Preparation (prep) of the operatory may include the assistant reviewing a checklist of items that are needed for the appointed procedure and subsequently ensuring that those items or supplies are available prior to the doctor’s entry into the operatory. In addition, “seating of the patient” ensures that the patient and his or her chart are brought to the appropriate operatory and the patient is greeted, made to feel comfortable, and draped for the procedure. The assistant may also preliminarily converse with the patient and generally address today’s treatment event. Also of interest in this demonstration is that the time slot is unavailable when the operatory is being disinfected, in spite of the fact that the patient is not physically present in the operatory.

The patient appointed to the time slot and the procedure planned is included under the fourth column in Table 12.3. Ms. Sad’s treatment is planned as a crown preparation and final impression. She has been scheduled in operatory #1 with Assistant W. A 1-hour total operatory time slot has been allotted to this procedure. Dr. Zip has been given only 20 total minutes to complete the procedure. The amount of time required for this treatment procedure (by this doctor) can only be known by the scheduler and/or doctor through trial and error over a period of several months. As an example, an additional 10 minutes could be made available to him by decreasing the amount of prep and seating time required for this patient and/or procedure. Ms. Sad, however, may be elderly with comorbid conditions requiring several blood pressure readings or more time to prepare her for the procedure. In this case time must be made up in the dismissal and/or disinfection time slots or through the doctor’s increased efficiency. A doctor could also alternately make up time through efficient use of the second operatory.

The opportunity to make up time through use of another operatory makes operatory scheduling more desirable, given a flexible and efficient staff. Notice the staggered scheduling required in order to effectively utilize the provider’s time between two operatories. Whenever both an operatory and a dentist are shown to be open in the same time slot, there is an opportunity for another appointment to be inserted. However, the amount of open time available dictates the procedure that can be performed within that time frame.

Disinfection and Preparation Time

The procedure determines the amount of preparation time and disinfection time that it takes to prepare a treatment room between patients. Hygiene procedures are the simplest and fastest types of dental treatments to prepare for in setting up an operatory and in disinfecting a treatment room. Hygienists use the same instruments on most all procedures. They have two basic trays: one for prophylaxis and one for deep scaling and curettage. Dentists, on the other hand, have many different types of treatment procedures requiring different instrumentation and equipment, as well as different time frames to complete these functions.

Root canal treatments have become very sophisticated when rotary instrument systems are used instead of hand instrumentation. Many of the rotary files can only be used once, and those that can be recycled must be monitored with each usage and inspected for damage before being used for the next procedure. Some practices that offer implants and other surgical procedures have specially designed rooms to be used specifically for those types of procedures. It may take up to 20 minutes to properly set up a room for an implant procedure. If they have the space, for efficiency, some practices use other rooms for patient sedation before moving the patient into the surgical treatment room. Documentation of the specific manufacturer and brand name of implants used in the procedure must be recorded. Sometimes it takes longer than was allotted in an appointment time slot to provide proper sedation for the patient. When this happens the doctor or hygienist has to wait and try again. All of this takes time that may or may not have been planned.

For every procedure performed in a dental office, the proper time needed to set up and disinfect before and after the treatment should be factored into the time that the treatment room is not available to any other procedure. These functions also occupy the assistant’s time both before and after the treatment procedure. Care should be taken when using operatory scheduling to consider procedure type, especially when scheduling a patient for treatment that requires the presence of both the assistant and the doctor. Some appointments, like denture adjustments and healing checks, do not require an assistant.

There are hundreds of different dental procedures that can be provided to patients. The doctor or assistant uses a basic exam instrumentation setup (mirror, explorer, and cotton pliers) for many of these procedures. Some offices use a tray and tub system in which all the materials and instruments are placed on a tray and all the supplies and equipment are placed in a tub that is either color coded or labeled for use with a particular procedure. Other offices stock each operatory with the basic supplies and only bring the necessary instruments from the sterilization room into the operatory. The tray and tub systems are broken down and disinfected away from the operatory. Those offices that stock supplies in the operatory treatment room must take the time to restock each room periodically, in addition to disinfecting after each use of the operatory.

Time Units by Procedure

The time it takes to set up and disinfect an operatory is easier to gauge than the time a particular doctor needs to perform a specific procedure. This is especially true of new doctors or even an experienced doctor who has incorporated a new procedure into the practice. Just remember that with every new thing there is a learning curve. Repetition leads to efficiency, and efficiency leads to decreasing the time needed to perform different dental procedures. An excellent idea is to periodically record the time doctors and hygienists need to perform different procedures.

The more information the scheduler has concerning a particular appointment prior to the appointment time, the more likely the appointment will be scheduled within the appropriate time slot. The specific tooth number, the surfaces to be treated on each tooth, and the total number of teeth to be treated at the next visit are “minimal information.” No scheduler will ever complain about being given too much information about the dental visit being scheduled. Typically doctors err on the side of giving too little information to the scheduler about the next appointment. This is not a desirable behavior.

Ten-minute time units allow for more flexibility in scheduling an appointment. When 10-minute time units are used in scheduling, it is much easier to salvage time over the course of a normal workday. “Ten-minute cultures” must be established over time in the dental office. Much of appropriate appointment scheduling is orchestrating a practice/patient rhythm. Procedures can be measured in terms of 10-minute time units. Hygiene appointments can be used as a basic example. Some offices schedule one hygiene appointment per hour. Not all prophylaxis take the entire hour to accomplish, but even if finished before the hour is over, the hygienist must wait until the next patient arrives for the next appointment. If, however, the hygiene appointments are scheduled every 50 minutes or five “10-minute” units of time for each appointment scheduled, 10 minutes are saved with each appointment. If appointments are scheduled on the hour, using the 50-minute time for cleanings, the next appointment will be scheduled for 10 minutes before the hour, the following appointment will be scheduled for 20 minutes before the next hour, and so on. For every eight appointments, eight units of time are saved (1 hour and 20 minutes in potential production time by the end of a typical 8-hour day). This will allow the hygienist to see nine patients instead of eight and have two units of time to “spare” at the end of the day.

Let us take this hygiene example and put some numbers with it. If the average hygiene appointment is a $100 production, the hygienist can treat five more patients over the period of 1 week. That increased production accumulates over a 1-year period to 300 more patients treated. Using these very conservative figures, an additional $30,000 in production could be scheduled for the year. These “spare units” can be thought of as “spare change,” which adds up to increased production, as well as efficiency in utilizing the resources of the practice.

Scheduling by Provider

This section includes a discussion of the four basic dental aspects that impact scheduling (type of procedure, order and sequence of procedures, variability of provider work habits, and patient preferences).

Patients form opinions about the dental office at all these levels, starting with their first contact with the office, whether it is on the phone, in person, or on the internet. Attention to details in all these levels of sequencing is critical. The recurring question that must be constantly asked at all levels is, how can we do this better? We must always look to the patients for the answers because all that we do is under their continual scrutiny.

Creating an efficient and productive schedule is similar to accomplishing successful dental treatment. There are certain principles that need to be honored, and there are systems that need to be followed. Schedulers must first be taught how long it typically takes each provider to do the different procedures that will be scheduled. They must be educated as to the setup and disinfection time it takes for particular procedures. It helps if this person has a working knowledge of the different procedures, but if not, the level of understanding of the procedures from a time standpoint can be taught. Not to have this working knowledge of the dental procedures limits the scheduler’s potential to achieve excellence in this area.

Type of Procedure

Procedures can be classified in many ways. Separate consideration of appointment time units can be given based on classes of dentistry. These class divisions could be made based on the following: examination and consultation, prophylaxis (with dentist review), diagnostic (referral to specialists), episodic treatment (hurting), simple restorative, cosmetic, evaluation of previous treatment effectiveness, treatment follow-up, and implementation of comprehensive long-term treatment plans. There are other ways to classify dentistry with regard to appointments, and remember, our concern is with our commodity—time.

Classes of dental appointments can be viewed strictly from the time requirements. There are long, intermediate, and short procedures. The long procedures would be those that require at least 1 hour of the doctor’s time. Intermediate appointments would require 30 minutes of the doctor’s time, while short appointments only require 10 minutes of the doctor’s time. An example of a long procedure could be a root canal, crown and bridge (preparation and final impression), or an implant procedure. An intermediate procedure could be fillings, extractions, or impressions for dentures or partial dentures. Short appointments are healing checks, denture adjustments, or hygiene and treatment planning exams.

Dentistry can also be classified according to the dollar amount of production for the different procedures. Using the cost of a crown as the basis for production, we divide these classes into primary, secondary, or tertiary. Primary procedures are procedures that use the cost of a crown or above. Secondary procedures are those that are about half the cost of a crown. Tertiary appointments are procedures that have no out-of-pocket cost to the patient at that appointment. In other words, the exam may simply be a follow-up exam or check-up to assess healing from a previous treatment.

Examples of primary procedures are partial dentures, veneers, implants, root canals, or completing several fillings during one appointment. Examples of secondary procedures are fillings, some surgical procedures, extractions, and teeth bleaching. An example of a tertiary appointment is a healing check exam. It is very important that when appointments are scheduled, these appointments are translated into production dollars by the scheduler. If the scheduler is not very conscious about these differences, a very busy schedule will be created, but if slots are filled with mostly tertiary appointments, there is no dollar value to the day’s production.

Dental consultant Cathy Jameson of Jameson and Associates refers to primary, secondary, and tertiary appointments as rocks, pebbles, and sand, using complementary definitions of each, as provided previously. She recommends preblocking the schedule for the placement of primary appointments in the schedule, with the daily goal to have at least half of the production scheduled in primary appointments and then building secondary and tertiary appointments around the primary appointments. This is an excellent system that makes primary appointments a priority for the scheduler and helps prevent being busy but not being productive. This sometimes requires negotiation skills on the part of the scheduler to gain patient acceptance in scheduling a primary appointment on a day and in a time slot that may be less desirable from the patient’s viewpoint.

Sequence of Procedures

Before an efficient and productive schedule can be sequenced properly based on the treatment required, the person scheduling the appointments must have a working knowledge of dental treatment procedures. Sequencing is the understanding of the steps necessary for treatment completion and how these steps integrate with appointment scheduling. For example, scheduling appointments involved in developing a patient denture includes an understanding of when the treatment sequence requires an appointment and what steps must be completed by the laboratory before the next appointment can be scheduled relative to this treatment procedure. Consider the following sequences in the development of a patient’s denture:

Many dental offices do not have schedulers with dental backgrounds. Schedulers must be educated in this area. There are certain principles that need to be honored, and there are systems that need to be followed in order to accomplish successful scheduling. Let’s deconstruct components of a crown procedure resulting from a previous diagnostic patient visit. For the current visit (treatment follow-up), the patient will be greeted by the assistant and prepped while seating. The dentist will apply a topical anesthesia and develop the operative model. The dentist spends time on tooth preparation to include taking the final impression. The assistant, depending on state rules, can complete the temporization of the prepared tooth. After the temporary is prepared the dentist returns and examines the temporary that has been fabricated for the tooth, makes any needed adjustments, and cements it. For this procedure, an hour has been allotted on the appointment book to accommodate the way Dr. X and Assistant Y work together. This procedure may require 30–40 minutes of doctor-devoted time. However, Dr. Z and Assistant W may require less or more time depending on their speed and efficiency.

Notice on Table 12.3 (operatory availability) that the dentist is not involved in all of the time that was allotted for the patient on the appointment book. This means that if the doctor works two operatories (side by side), another patient can also be seen during this time period. If the second patient is also a primary procedure (like the crown procedure), then staggering the appointment time by starting the first patient on the hour and the second patient on the half hour would allow the dentist to walk away from the first patient to the second patient and complete them both in about an hour’s time. However, without two assistants this would not be possible.

Let’s deconstruct components of an examination for a 6-year-old child. The first dental visit should be allotted a full 30 minutes. This allows time for the assistant to make both the child and the parent comfortable and then seat the child, describe prophylaxis techniques, expose a panoramic radiograph of the child’s teeth, and determine how the child will respond to the examination. The panoramic should be completed and available for the dentist to review prior to his or her entering the operatory. The dentist primarily spends time explaining the panoramic results and developing a plan of action, if necessary, for the child’s next visit. Within this 30-minute appointment interval, this examination procedure may require only 5–10 minu/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses