New technique for trigeminal neuralgia

Gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery

• New minimally invasive technique for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia.

• It uses beams of radiation usually in doses of 70–90 Gy units, converging in 3 dimensions to focus precisely on a small volume.

• This method relies on precise MRI sequencing that helps localization of the beam and allows a higher dose of radiation to be given with more sparing of nerve tissue.

• Advantage of this technique is that it is particularly helpful for elderly patients with a high surgical risk.

Q. 2. Define pain. Classify facial pain. Describe the aetiopathogenesis, clinical features and management of atypical facial pain.

Or

Give the differential diagnosis of pain in and around the tooth.

Or

Describe the ‘pain in and around the tooth’. Mention the treatment.

Ans. Pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.

Classification of orofacial pain

The American Academy of Orofacial Pain has classified orofacial pain as follows:

Intracranial structures

Extracranial structures

Musculoskeletal disorders

Neurovascular disorders

Neurologic disorders

Bell WE (1989) has classified orofacial pain as follows:

Axis I (Physical conditions)

Somatic pain

Neuropathic pain

Axis II (Psychologic conditions)

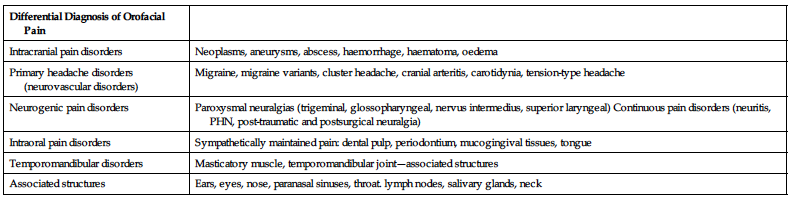

| Differential Diagnosis of Orofacial Pain | |

| Intracranial pain disorders | Neoplasms, aneurysms, abscess, haemorrhage, haematoma, oedema |

| Primary headache disorders (neurovascular disorders) | Migraine, migraine variants, cluster headache, cranial arteritis, carotidynia, tension-type headache |

| Neurogenic pain disorders | Paroxysmal neuralgias (trigeminal, glossopharyngeal, nervus intermedius, superior laryngeal) Continuous pain disorders (neuritis, PHN, post-traumatic and postsurgical neuralgia) |

| Intraoral pain disorders | Sympathetically maintained pain: dental pulp, periodontium, mucogingival tissues, tongue |

| Temporomandibular disorders | Masticatory muscle, temporomandibular joint—associated structures |

| Associated structures | Ears, eyes, nose, paranasal sinuses, throat. lymph nodes, salivary glands, neck |

Atypical odontalgia (Atypical facial pain)

• The term ‘atypical odontalgia’ is used when the pain is confined to the teeth or gingivae, whereas the term ‘atypical facial pain’ is used when other parts of the face are involved.

• Feinmann characterized AFP as a nonmuscular or joint pain that has no detectable neurologic cause.

• Atypical facial pain was described by Truelove and colleagues as a condition characterized by the absence of other diagnoses and causing continuous, variable-intensity, migrating, nagging, deep, and diffuse pain.

• Recent advances in the understanding of chronic pain suggest that at least a portion of patients who have been diagnosed with AFP may be experiencing neuropathic pain.

Aetiology and pathogenesis

• There are several theories regarding the aetiology of AO and AFP. One theory considers AO and AFP to be a form of deafferentation or phantom tooth pain.

• This theory is supported by the high percentage of patients with these disorders who report that the symptoms began after a dental procedure such as endodontic therapy or an extraction.

• Others have theorized that AO is a form of vascular, neuropathic or sympathetically maintained pain.

• Other studies support the concept that at least some of the patients in this category have a strong psychogenic component to their symptoms and that depressive, somatization and conversion disorders have been described as major factors in some patients. It is frequently difficult to accurately study the psychological aspects of a chronic pain.

Clinical manifestations

• The major clinical manifestation of AFP is a constant dull aching pain without an apparent cause that can be detected by examination or laboratory studies.

• It occurs most frequently in women in the fourth and fifth decades of life, and women make up more than 80% of the patients.

• The pain is described as a constant dull ache. There are no trigger zones, and lancinating pains are rare.

• The patient frequently reports that the onset of pain coincided with a dental procedure such as oral surgery or an endodontic or restorative procedure.

• Patients also report seeking multiple dental procedures to treat the pain; these procedures may result in temporary relief, but the pain characteristically returns in days or weeks.

• Other patients will give a history of sinus procedures or of receiving trials of multiple medications, including antibiotics, corticosteroids, decongestants or anticonvulsant drugs.

• The pain may remain in one area or may migrate, either spontaneously or after a surgical procedure.

• Symptoms may remain unilateral, cross the midline in some cases, or involve both the maxilla and mandible.

Diagnosis

• A thorough history and examination including evaluation of the cranial nerves, oropharynx, and teeth must be performed to rule out dental, neurologic or nasopharyngeal disease.

• Examination of the masticatory muscles should also be performed to eliminate pain secondary to undetected muscle dysfunction.

• Laboratory tests should be carried out when indicated by the history and examination. Patients with AFP have completely normal radiographic and clinical laboratory studies.

Management

• Once the diagnosis is confirmed, it is important that the symptoms are taken seriously and are not dismissed as imaginary.

• Patients should be counselled regarding the nature of AFP and reassured that they do not have an undetected life-threatening disease and that they can be helped without invasive procedures.

• When indicated, consultation with other specialists such as otolaryngologists, neurologists or psychiatrists may be helpful.

• Tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline and doxepin, given in low to moderate doses, are often effective in reducing or in some cases eliminating the pain.

• Other recommended drugs include gabapentin and clonazepam. Some clinicians report benefit from topical desensitization with capsaicin, topical anaesthetics or topical doxepin.

Q. 3. Describe in detail aetiology, clinical features, differential diagnosis and management of periodic migrainous neuralgia.

Ans.

Aetiology and pathogenesis

• The classic theory is that migraine is caused by vasoconstriction of intracranial vessels, which causes the neurologic symptoms, followed by vasodilation which results in pounding headache.

• Newer research techniques suggest a series of factors, including the triggering of neurons in the midbrain that activate the trigeminal nerve system in the medulla, resulting in the release of neuropeptides such as substance P.

• These neurotransmitters activate receptors on the cerebral vessel walls, causing vasodilation and vasoconstriction.

Types of migraine

There are several major types of migraine:

Clinical manifestations

• Migraine is more common in women.

• Classic migraine starts with a prodromal aura that is usually visual but that may also be sensory or motor.

• The visual aura that commonly precedes classic migraine includes flashing lights or a localized area of depressed vision (scotoma).

• Sensitivity to light, haemianaesthesia, aphasia or other neurologic symptoms may also be part of the aura, which commonly lasts from 20 to 30 minutes.

• The aura is followed by an increasingly severe unilateral throbbing headache that is frequently accompanied by nausea and vomiting.

• The patient characteristically lies down in a dark room and tries to fall asleep.

• Headaches characteristically last for hours up to 2 or 3 days.

• Common migraine is not preceded by an aura, but patients may experience irritability or other mood changes.

• The pain of common migraine resembles the pain of classic migraine and is usually unilateral, pounding and associated with sensitivity to light and noise. Nausea and vomiting are also common.

• Basilar migraine is most common in young women. The symptoms are primarily neurologic and include aphasia, temporary blindness, vertigo, confusion and ataxia. These symptoms may be accompanied by an occipital headache.

• Facial migraine (carotidynia) causes a throbbing and/or sticking pain in the neck or jaw. The pain is associated with involvement of branches of the carotid artery rather than the cerebral vessels.

• The symptoms of facial migraine usually begin in individuals who are 30–50 years of age.

• Patients often seek dental consultation, but unlike the pain of a toothache, facial migraine pain is not continuous but lasts minutes to hours and recurs several times per week. Examination of the neck will reveal tenderness of the carotid artery.

• Face and jaw pain may be the only manifestation of migraine, or it may be an occasional pain in patients who usually experience classic or common migraine.

Treatment

• Patients with migraine should be carefully assessed to determine common food triggers. Attempts to minimize reactions to the stress of everyday living by using relaxation techniques may also be helpful to some patients.

• Drug therapy may be used either prophylactically to prevent attacks in patients who experience frequent headaches or acutely at the first sign of an attack.

• Drugs that are useful in aborting migraine include ergotamine and sumatriptan, which can be given orally, nasally, rectally or parenterally. These drugs must be used cautiously since they may cause hypertension and other cardiovascular complications.

• Drugs that are used to prevent migraine include propranolol, verapamil and TCAs. Methysergide or monoamine oxidase inhibitors such as phenelzine can be used to manage difficult cases that do not respond to safer drugs.

Short essays

Q. 1. Aetiology, signs and symptoms of Bell palsy.

Or

Bell palsy.

Ans.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses