Chapter 10

Sugars in the diet

INTRODUCTION

Globally, sugar consumption has tripled in the past 50 years [1]. Although, arguably, fewer and fewer of us add visible sugar in our tea, and sprinkle less over our cereals and puddings, we are actually consuming far more invisible sugar due to an increased appetite for processed foods. For example, the average can of regular cola contains seven teaspoons of sugar.

The consumption of sugar in its various forms has long been associated with the development of caries (see Chapter 5). More recently, sugar has been identified as a major factor in the growing problem of obesity.

Some scientists have linked sugar consumption with a growth in certain diseases (such as cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes), as well as contributing to childhood behavioural problems and detrimental health effects during weaning.

THE COMA PANEL ON DIETARY SUGARS

In 1986, a committee was set up by the UK government to investigate all aspects of diet. The Committee on Medical Aspects of Food and Nutrition Policy (COMA) established the Panel on Dietary Sugars to look at the role of sugars in the diet.

In 1989, the Panel concluded that the role of sugars in the development of obesity was not clear, but they recommended that when a person is obese, the consumption of non-milk extrinsic sugars (NMES) should be restricted, combined with a reduction in fat intake and the uptake of regular physical exercise.

The UK Health Education Authority (later subsumed into NICE) set out the Panel’s findings in a booklet called Sugars in the Diet [2].

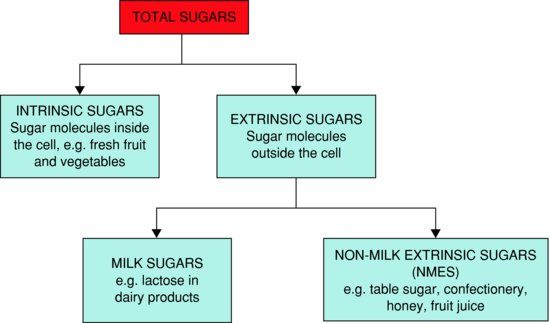

COMA classification of sugars (Figure 10.1)

COMA distinguishes between sugars held within the cell structure of food (natural sugars, known as intrinsic), and those which have been released from the cell structure (natural or added sugars, known as extrinsic). Certain types of sugar (such as fructose) can be both extrinsic and intrinsic in nature depending on their state. Milk sugars are classified as extrinsic sugars.

Figure 10.1 Classification of sugars following the COMA report (From Levine, R.S. & Stillman-Lowe, C.R. (2004) [3]. Reproduced with permission of the British Dental Association)

Intrinsic sugars

Intrinsic sugars are found in the cell walls of whole fruits and vegetables. They include fructose, glucose and sucrose, which do not begin to break down in the mouth, and are therefore generally less cariogenic than extrinsic sugars.

However, it is not quite as simple as that. Fructose in the skin of an apple (which begins absorption in the stomach) is less cariogenic than fructose in apple juice which is classified as an extrinsic sugar. Therefore, although fruit juice can be labelled as having no added sugar it is rendered cariogenic, as fructose is removed from the plant cell wall and is broken down by salivary amylase in the mouth.

Extrinsic sugars

Extrinsic sugars are also known as NMES (think enemies) and were found by the COMA Panel to be the sugars most responsible for dental caries.

NMES include:

- Sucrose.

- Fructose.

- Glucose.

- Dextrose.

- Maltose.

NMES are found in processed foods such as confectionery, soft drinks, biscuits, cakes, as well as naturally in honey and fruit juice (as we have seen).

Although the sugars (glucose and fructose) in honey are natural like fruit juice, honey’s consistency facilitates its initial breakdown in the mouth, and it is therefore considered to be cariogenic. Honey is often marketed as a natural ‘healthy’ food, which it is, but it should be remembered that it has the potential to cause caries when/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses