Chapter 1

Introduction and Overview

This book is aimed at providing you with necessary concepts and perspectives for making practice transition decisions. The emphasis is on presenting good ideas in as fair and as balanced of a manner as possible. We are not trying to sell you anything other than information for decision making.

Assembling all that is necessary for practice transition in a single volume is a daunting task. More detail treatments are available for many of the topics addressed here (for example, see a partial list of American Dental Association [ADA] publications at the end of this chapter). Still, this book provides essential information not typically available in one book.

This chapter explores career choices, the current dental market and its implications for you, the “Bermuda Triangle” of practice transition, and the selection of key advisors for your practice transition and life.

Career Choices

The future you see is the future you get.

The major career question has already been answered. You are in dental school or have already graduated. For those still in dental college, questions often center on what area of dentistry: a generalist, specialist, public health, military, dental educator, or are you one of the few that will join one or more of your relatives in “your” family practice? The ADA’s Success Seminar Manual (2005–2006), chapter 1, outlines many of the advantages and disadvantages of various career options. Our purpose here is not to duplicate that information but, rather, to take a step back and have you reflect on the process of making a career choice and some of the key issues in that process.

Most dental students in their first and second years are asking, now that I am in dental school, what is next? Questions begin to race through your mind. Where do I want to live? Or if married, where do we want to live? If I specialize, how does that affect where I can live? Do I want a metropolitan lifestyle, rural lifestyle, or something that allows a little of both? If you have or are planning a family, you find yourself asking about the best educational and social opportunities for your children. What values do you want your children exposed to day by day? For those who follow a faith-based lifestyle, where does God want me to be? Can I get student loans repaid, and should this, based on interest rates, be a slow or a quick repayment process?

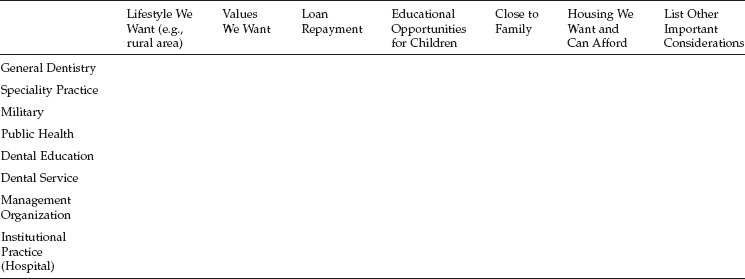

The questions listed above are by no means an exhaustive list. They are meant to get you thinking about the relationships between you, your family, the location of your practice, and the type of practice (general, speciality, etc.). The matrix in Table 1.1 is meant to give you a starting point for your decision-making process. You can list across the top all the issues you need to consider in making a decision about the type of dentistry you want to practice and then see which area of dental practice best meets most or all of your criteria. Approach the matrix (decision-making process) with the following in mind:

- Gather input from the people closest to you who will be affected by your decision.

- What seems like a good idea in your second year of dental school may not seem like a good idea in your third year of dental school. Be flexible; at times, life can take a sharp turn.

- It is called a decision-making process for a reason. Decisions, especially of the nature you are considering, take data or input that take time. Be patient.

A question that often arises when working with people making important decisions is, what if I do all the right things and I am comfortable in my decision, but after being in the practice I do not like it? This is a challenging and multi-dimensional question with both a simple and a complex answer. The simple answer is that you can always move, though this may take some time depending on your situation. There is a demand for dentistry in many places. The complex answer is based on a series of questions:

- What do you not like about the practice?

- What do you not like about the community?

- Can anything be changed that would make you more at ease?

- What would you do differently in choosing a practice?

- How does what you are experiencing differ from what you expected?

If you invest the time to go through the series of questions with family, and if you are in a position of working for (associateship) or with (partnership or buyout) another dentist, you may find out that you can resolve the issues causing your discontent. However, if you are not able to resolve the issues causing your discontent by answering the questions, you are better prepared to decide on what you will do next.

Some points to remember when making decisions, adapted from McDaniels et al. (1995):

Table 1.1. Decision matrix.

- Decisions are tentative; you can change your mind.

- There is usually no one right choice.

- Deciding is a process, not a static one-time event. We are constantly reevaluating in light of new information.

- When it comes to a career decision, remember you are not choosing for a lifetime. Choose for now and do not worry whether you will still enjoy it in 20 years. Life is fluid and change occurs.

- There is a big difference between decision and outcome. You can make a good decision based on the information at hand and still have a bad outcome. The decision is within your control, the outcome is not. All decisions have an element of risk.

- Think of the worst outcome. Could you live with that? If you could live with the worst, then anything else does not seem that bad.

- Try to avoid either/or thinking: usually there are more than two options.

The Current Market and Its Implications for You

The dental market in the early 21st century presents some unique opportunities and challenges for dentists and patients alike. These exigencies have profound implications for you. Let us consider the platinum age of dentistry and the present market as representing both the best of times and the worst of times as a background for this book.

The Platinum Age

We stake no claim on being the first to call this the platinum age in dentistry. The term has been used since at least the first reference we could find, in the spring of 2000 (Takacs 2000). So, why are people calling this the platinum age in dentistry? Much of the rationale hinges on the numbers, most of which you have probably already heard and so we will only point out the most critical ones.

Our population is living longer and is more likely than a generation or two ago to have had relatively good oral health. With fewer missing teeth and more teeth and supporting structures to be maintained and restored, there is, plainly speaking, more work to be done. Simultaneously, the number of dental graduates is still significantly less than the number of dentists who will be retiring. As of this writing, a few new dental schools are in various stages of development. Still, the gap between retirees and new graduates will likely remain somewhere in the lower 4,000s, while the need is in the area of 4,650 (Chou 2006). Further, the number of dentists per 100,000 population is projected to decline from a peak of 59.5 in 1990 to 43 in 2020 (Valachovic et al. 2001).

In addition, according to Mark Maremont of the Wall Street Journal, as of 2005, general “dentists in the past few years have started making more money than many types of physicians, including internal medicine doctors, pediatricians, psychiatrists, and those in family practice.” This trend is likely to continue, if not be magnified. Granted, some physician specialists such as radiologists and cardiologists still enjoy incomes greater on average than that of general dentists and specialist dentists. However, remember that these medical specialists, like their counterparts in dentistry, have more years of education than general dentists before earning large incomes. So, the time value of money also has to be considered in understanding this as the platinum age of dentistry.

While this certainly seems to be the platinum age of dentistry for dentists, we would be remiss if we failed to mention that such is not the case for certain groups of patients. Patients lacking dental insurance, patients in some rural areas, and patients with lower incomes are all less likely to receive the care they need. So while this is the platinum age for providers, it is the stone age for certain patient groups. Since you will be receiving much, we hope you will consider giving back much in whatever manner you are led to help close the gap in access to care. Options are many but include state Medicaid programs, nonprofit clinics, Missions of Mercy (volunteer weekends for providing care for the poor), and even providing free or discounted care or negotiated care based on bartering.

The Best of Times, the Worst of Times?

A particularly astute and famous quotation from Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities accurately describes the current transition opportunities for the general practice of dentistry: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity.” How do these literary observations relate to transitioning into private practice?

In so many ways, it is indeed the best of times. Student choices for entering private practice resemble a buffet: do I prefer Chinese food tonight, or perhaps seafood, or Italian instead? There are so many choices, in fact, that we have heard it said that it is very difficult to fail, for example, in buying an existing practice with healthy financial numbers. There is little doubt that in a myriad of dimensions in this platinum age of dentistry, this is the best of times.

However, it is also, ironically, the worst of times in a sense. Why? Because it is sometimes a struggle to choose what you really want from the buffet! Having to choose from two or more favorable options is still conflictive. There is a need, among other skills, to be able to objectively evaluate the options that are available in order to make an informed decision. Further, the word has now been widely broadcast: dental students will likely become wealthy in their lifetimes. This means that many individuals and corporations are, metaphorically speaking, circling above the heads of dental students, not waiting for them to die, but waiting for them to live out their careers and to share in the revenue stream! The need to be watchful regarding personal and business insurance, regarding practice transition concepts and processes, and regarding investing has never been greater.

Amidst this best of times and worst of times, arguably some wisdom and strangeness have emerged, as well as some sense of total devotion to certain models and concepts and some sense of credulity (that there is no right way). We are, frankly, surprised at the way that some associateship arrangements and practice purchases are structured, particularly in this platinum age. Still, there apparently is room in the competitive market for contracts that seem to be heavily biased in some ways for the owner-dentist. Some very competitive market conditions give the owner-dentist incredible negotiating positions that, in such a context, may warrant many fewer advantages for an associate position and much higher prices for practices. Some consulting firms market and implement their business models of transitioning practices across incredibly variable market conditions, causing others to scratch their heads and wonder how and why.

One of the main purposes of this book is to provide for you some perspective of wisdom based on historically proven concepts so that you can sort your way through this best of times and worst of times, through the fog of strangeness. In the end, there may not be any absolutely and completely “right” way to structure an associateship experience or to purchase a practice. Nevertheless, there certainly are reasonable ranges within which these endeavors can be structured, and some of these will be more or less favorable to you. This, then, calls for you to be a wise consumer.

The “Bermuda Triangle” of Practice Transition

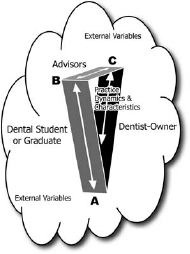

Transitioning from dental school or early career tracks (military or public health) into private practice represents a tenuous activity in which opportunities can readily disappear into oblivion. Hence, the reference in the heading to the infamous “Bermuda Triangle,” where, according to folklore and myth, ships and planes have disappeared without a trace (see Figure 1.1). Regardless of the legitimacy of the Bermuda Triangle in history, as a metaphor the name helps us to focus on the particularly tender and easily tipped process through which recent dental graduates enter the business world by trying to start, buy, buy into, or become associates of dental practices.

The three-dimensional triangle in the practice transition model includes these parties/sides: the dental student/graduate, the owner-dentist(s), and the advisors for both parties (see the model itself). Inside the model are the particular dynamics and characteristics of the practice that, depending on how they “load” with each party, can also readily sink the deal. Outside the model are the external variables influencing the practice. For example, suppose a prospective buyer understood that the staff in a given practice would be staying after the purchase, only to discover that all the team members are leaving. Such information could easily sink the deal, as could discoveries related to the opinions of area dentists, overhead percentages, and so forth.

Figure 1.1. The “Bermuda Triangle” of practice transition.

Three specific principles undergird this model; principles that, admittedly, are themselves subject to debate.

Principle #1: No single party in the transition process should retain all of the power or control. We believe this principle is an equitable one. The dentist-owner, obviously, enjoys more “position power” than a prospective associate or buyer. Still, the interests of the latter simply cannot be shelved in favor of the dentist-owner. Some sense of balance and mutual interest must be preseved if a practice transition toward associating or purchasing is to be successful.

Principle #2: Each party has competing interests, and thus this process requires some degree of negotiation, ranging from making minor adjustments to standardized employment agreements to developing unique contracts. Sometimes individuals have interests and needs that, on the surface, appear somewhat strange. These may arise from personal history. Occasionally, for example, an associate-ship contract will contain some very specific provision regarding a rather obscure circumstance that presented itself in a previous associate’s employment (for example, thou shalt not approve the purchase of any dental supplies).

Principle #3: This process of negotiation can easily/readily “tip” or fall (sink into the ocean) if any party maintains an unreasonable bargaining position or an unreasonable stance. We are of the opinion that practice transitioning needs to major in majors rather than get tipped by relatively minor issues. It seems unwise to walk away from an associateship contract because of a dispute about who pays for malpractice insurance for 1 year or because of a disagreement about whether the practice is worth $300,000 instead of $315,000. Fifteen thousand dollars buys a small car these days. Yet, it is our opinion that you do not walk away from a practice sale for $15,000 (though maybe for $50,000).

Let us explore the nexus of the triangle where competing interests meet. At juncture “A” reside the relationships and interactions between the dental student (or recent graduate) and the dentist-owner. How do the personalities mesh, the philosophies of practice, the values governing behavior, the type of dental services to be provided/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses