Diagnosis and Treatment Planning in Restorative Dentistry

Periodontal Diagnosis

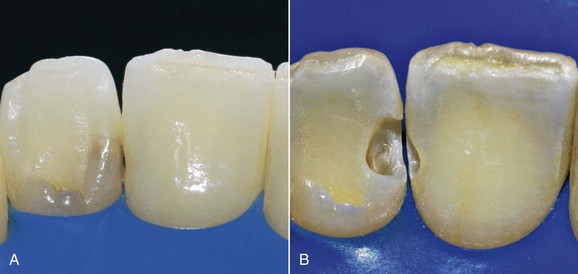

In restorative dentistry the planning of treatment cannot be based on mere examination of the single tooth to be restored, but should encompass assessment of the oral cavity as a whole. It must thus outline a global treatment plan that takes both hard and soft tissues into account and considers the tooth as a functional unit composed of several structures (Figure 1-1).

Figure 1-1 Algorithm of the global treatment plan.

Notes on the Anatomy and Histology of the Dental Functional Unit

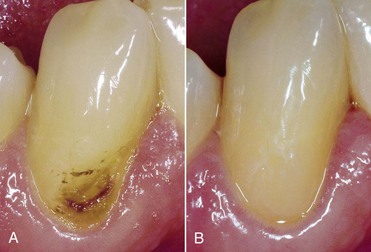

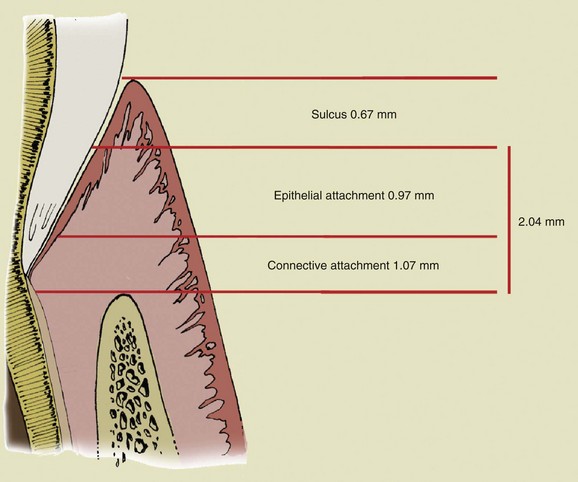

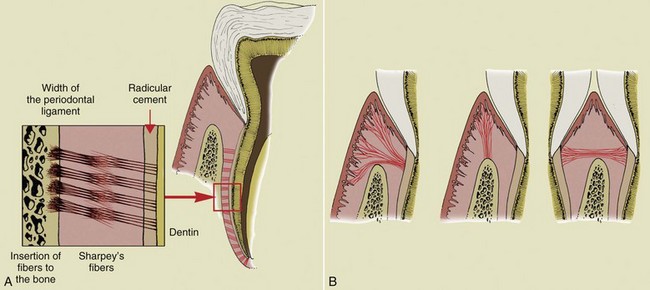

The key aspect of periodontal diagnosis is identification of local and systemic risk factors that can affect the anatomic structures and thus jeopardize the stability and even the survival of the tooth. The following structures are involved in the process (Figure 1-2): radicular cementum, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone in the strict sense of the term. In 1961 Gargiulo, Wentz, and Orban described the concept of biologic width as a space of about 2 mm composed of the connective tissue attachment and the epithelial attachment, an inviolable space for dental and periodontal health (Figure 1-3).

Figure 1-3 Biologic width.

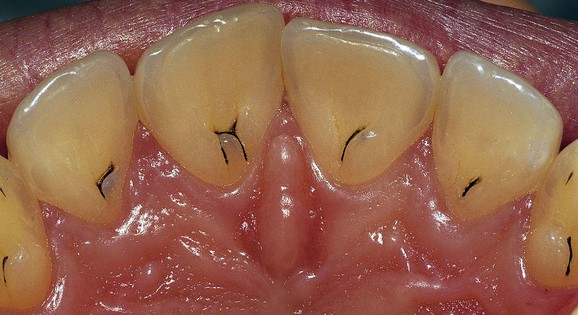

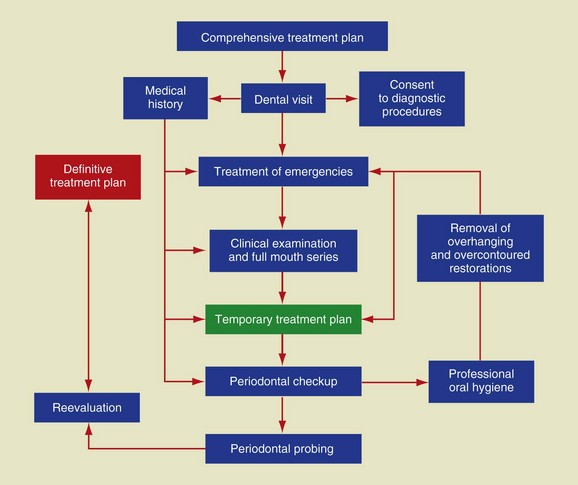

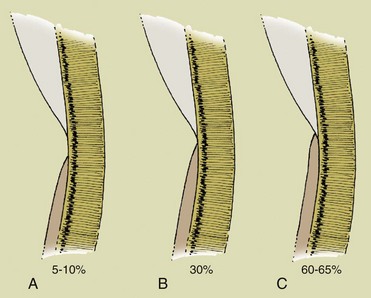

An important anatomic variable is the arrangement of the cemento-enamel junction. When the cementum does not reach the enamel (Figure 1-4, A) and thus exposes a small amount of dentin, the risk of attack by bacterial, chemical, or mechanical agents is greater. In this case gingival recessions and erosion of the exposed radicular dentin can frequently be observed (Figure 1-5).

Figure 1-5 Gingival recessions and root exposures. The subject has an interrupted cemento-enamel junction (see Figure 1-4, A), which favors the onset of soft-tissue alterations with more severe lesions on the left side (because the patient is right handed, brushing is stronger on the left side of the mouth).

Diagnosis

Medical History

Not only is medical history an important component when obtaining the patient’s general data and clinical history, but it permits identification of local and systemic factors or diseases that can alter the equilibrium of the oral cavity (Figures 1-6 to 1-11)—for example, stress, smoking, poor oral hygiene, drug abuse, and iatrogenic injuries.

Figure 1-9 Radiograph of the patient in Figure 1-8.

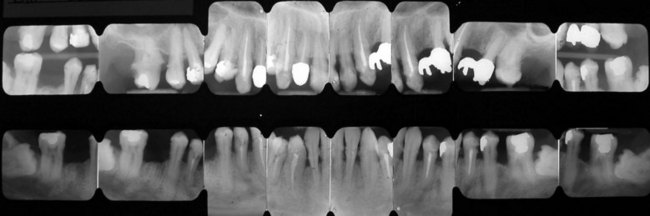

Figure 1-11 A full mouth series shows no periodontal disease and the presence of faulty restorations that prevent correct periodontal probing (see Figure 1-10). During professional oral hygiene maneuvers it is necessary to remove overhangs to enable soft-tissue reconditioning.

Periodontal Probing

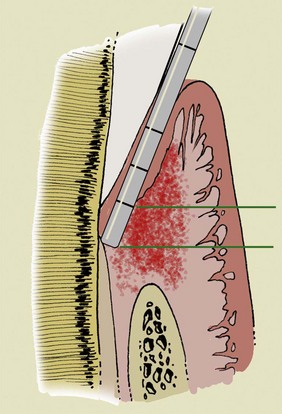

Periodontal probing was—and still is—an important factor in determining the presence and severity of periodontal disease (Figure 1-12). From a diagnostic standpoint, periodontal probing and assessment of the following three parameters are crucial.

Figure 1-12 Radiographic image of periodontal probing.

1. Pocket depth: (PPD—probing pocket depth) Distance measured from the tip of the probe (located at the apex of the gingival sulcus) to the gingival margin. Inflamed tissues are much looser than the healthy ones. Consequently the probe penetrates more deeply with respect to the actual depth of the periodontal pocket (clinical parameter). Probing performed before the causal therapy will present greater depths than is actually the case; the bottom of the pocket is not a reference point for assessing the loss of periodontal attachment (histologic parameter).

2. Attachment level: (PAL—probing attachment level) Distance between the cemento-enamel junction and the lowermost point of the gingival sulcus. It is clear that attachment level and pocket depth will exhibit identical values when the gingival margin and cemento-enamel junction correspond.

3. Bleeding on probing: (BOP—bleeding on probing) An inflammation index that alone does not provide information regarding the aggressive behavior of the disease.

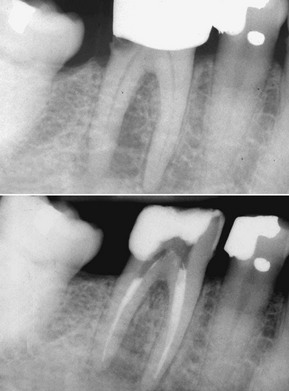

In 1979 Maynard and Wilson demonstrated that when the biologic width is violated during restoration, the result is comparable to periodontal disease. Figure 1-13 shows that faulty restoration causes resorption of the bony ridge, as in the case of periodontal disease.

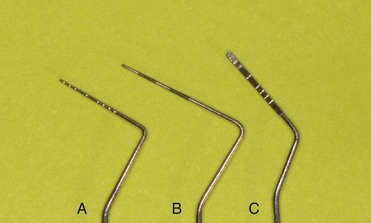

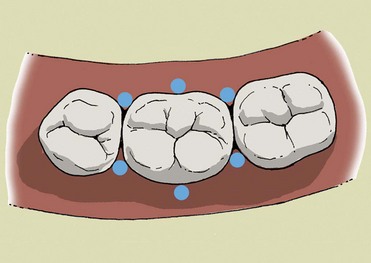

Periodontal probing should follow certain criteria (pressure, probing sites), bearing in mind that measurements are affected by operator-dependent variables (pressure) and independent variables (type of probe, status of the soft tissues) (Figures 1-14 to 1-16).

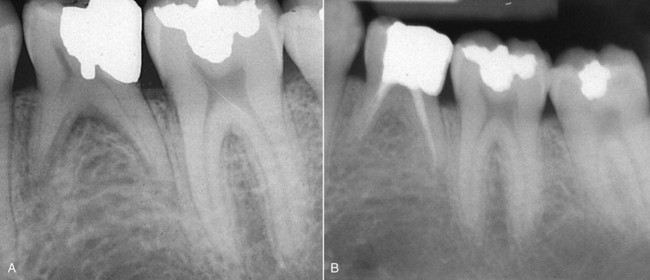

Initial preparation (causal therapy) paired with concomitant removal of the causes of inflammation (calculus and overhanging restorations) improves the conditions of the soft tissues, which will be firmer at the next probing. This explains why, even if there are pockets, reevaluation can yield a lower probing score than what was assessed at the initial examination, even in cases of no attachment gain (Figures 1-17 and 1-18).

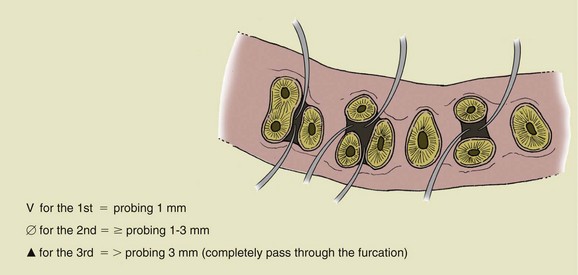

On the periodontal chart the results of probing at the furcation areas will be described as degree 1, 2, or 3 (see Figure 1-21). An effective system for quickly viewing the status of the furcation areas is to draw a symbol on the chart beside the tooth (Figures 1-19 to 1-21).

In case of abscess (Figure 1-22), probing values are not significant, because a probe inserted in this area will penetrate past the pocket depth and will not provide any useful information. In case of marginal gingivitis (Figure 1-23) a pocket depth of 4 to 5 mm might revert to normal values (less than 3 mm) after the cause of inflammation is removed, owing to reduced tissue edema.

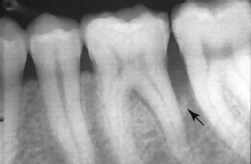

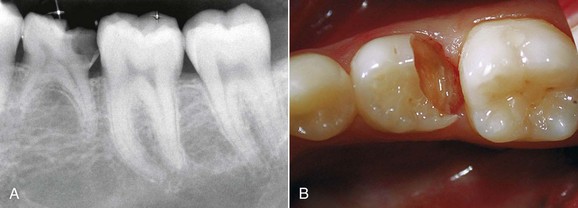

A different scenario occurs when inflammation is caused by a vertical fracture; in this case the periodontal probe will penetrate deeply only at the fracture site because of absence of the ligament and not because of tissue laxity (Figure 1-24).

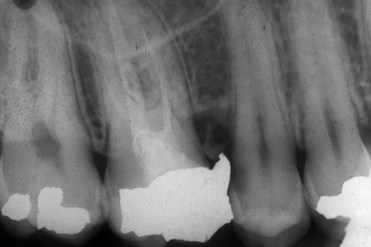

Radiographs

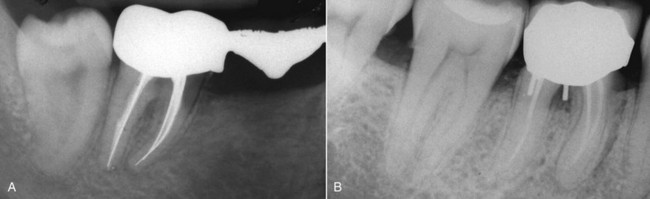

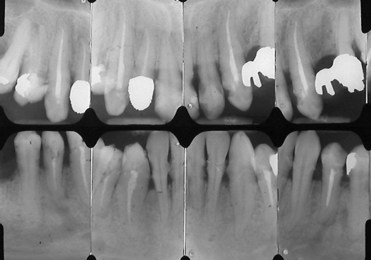

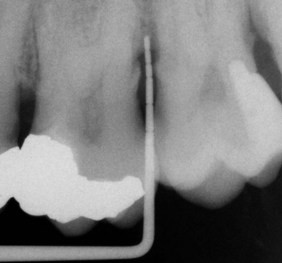

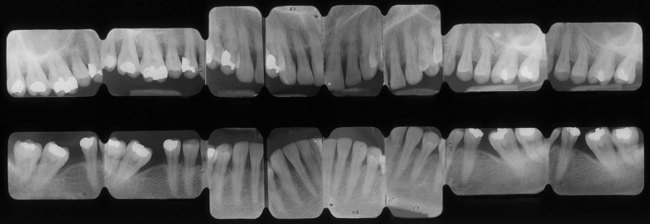

A full mouth series of radiographs is indispensable for drawing up a correct treatment plan. With respect to the panoramic radiograph this makes it possible to assess if the disease affects only a few teeth or if it is a diffuse form (Figure 1-25). The subsequent treatment plan varies according to the cause of the disease. Generalized defects demand complete treatment in conjunction with causal therapy, whereas treatment of localized defects involves only the affected teeth. To complete the full mouth series it is useful to take two bitewings (Figure 1-26). The number of radiographs and their distribution may change—for example, 16 radiographs, distributed as follows, can be taken even if teeth are missing (Figures 1-27 to 1-36):

Figure 1-25 Full mouth series of 16 radiographs.

Figure 1-26 Bitewing radiographs.

Radiographs

Figure 1-35 Periodontal pseudopockets. The full mouth series of the same patient shown in Figure 1-34 reveals the absence of periodontal disease. The 6- to 7-mm probing depth is not related to a lesion but to the different heights of the interproximal peaks of bone, caused by the mesial inclination of the tooth. The treatment is not periodontal but surgical (extraction of the third molars) and orthodontic (uprighting of the second molars), followed by prosthetic or implant treatment.

Laboratory Testing

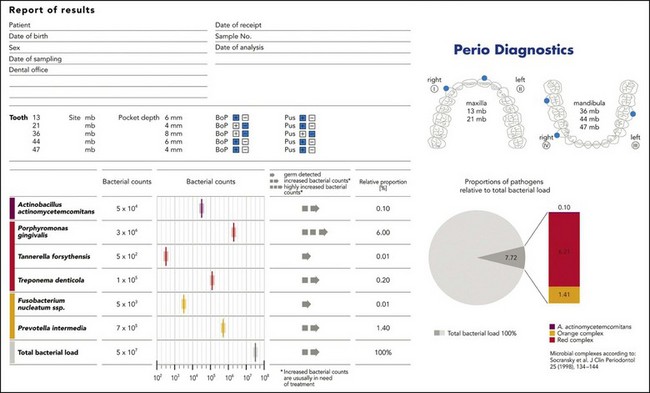

Laboratory tests may be useful for establishing the etiologic diagnosis of the periodontal disease and its treatment. They can be easily performed with sterile endodontic paper points (Figure 1-37) introduced into the active periodontal pockets and then placed in proper containers to be sent to the microbiology laboratory for testing (Figure 1-38).

Figure 1-38 Report of laboratory tests.

Treatment

Etiologic Phase

When there is thin tissue, proper oral hygiene helps preserve the structures and teeth (Figure 1-39).

Figure 1-39 Thin and scalloped gingival phenotype.

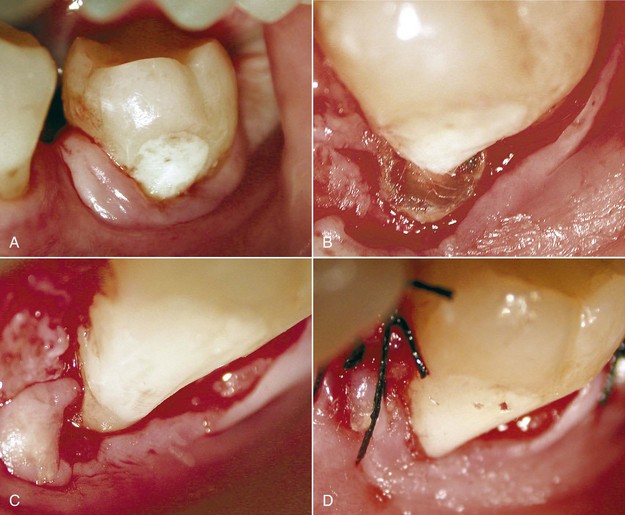

In these types of patients the equilibrium of the dentoperiodontal unit is very delicate, and if oral hygiene maneuvers are done incorrectly or are overly aggressive, recessions or changes in the gingival scalloped profile are common findings. The status of the hard tissues (caries), gingiva (recessions), and morphology (phenotype) guide therapeutic decisions. For instance, sometimes placement of ceramic veneers can avoid involvement of the marginal periodontium (Figures 1-40 through 1-43). Patients with a thick and scalloped phenotype (Figure 1-44) have less chance of developing gingival recessions and show a higher resistance to mastication and hygiene-maneuver traumas. Despite the presence of inflammation, this situation can be reversed through proper oral hygiene.

Figure 1-44 Thick and scarcely scalloped gingival phenotype.

Figure 1-40 Initial status.

Figure 1-41 Causal therapy and polishing.

Figure 1-42 Cosmetic mockup.

Figure 1-43 Cementation of feldspathic ceramic veneers.

Caries Diagnosis

The goals of restorative dentistry are as follows:

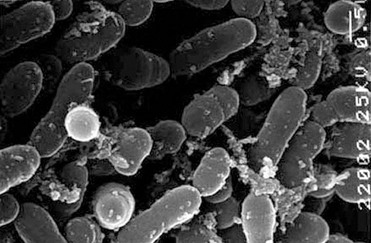

From an etiologic standpoint, caries is an infectious disease, meaning that it is caused by a microbial factor, which represents the causal agent. It is common knowledge that it can be transmitted to experimental animals (Figure 1-56). It is characterized by progressive destruction of the hard tissues of the tooth, through both decalcification of the mineral component and proteolysis of the organic component, which result in cavitation.

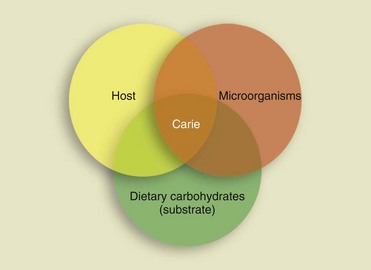

The 1960 Keyes diagram (Figure 1-57) shows the interaction of the three factors that are decisive for the onset of the caries lesion:

Caries Classification

Anatomopathologic Classification

Enamel Caries

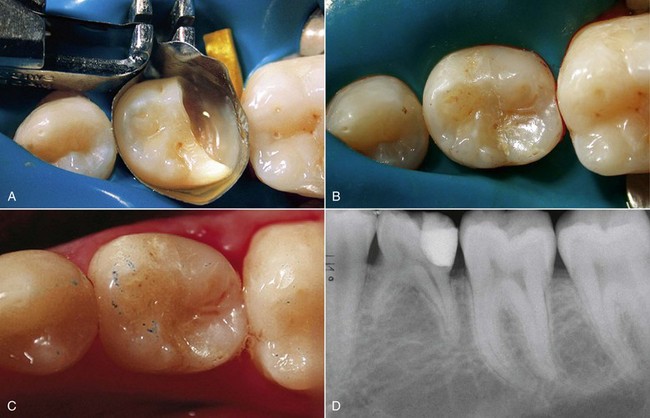

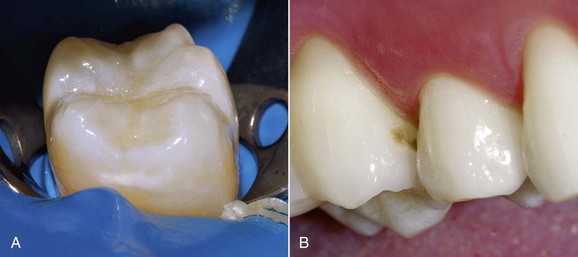

From an anatomopathologic standpoint, enamel caries on smooth surfaces appears macroscopically as an opaque whitish spot that can develop into cavitation or become pigmented (Figures 1-58 and 1-59).

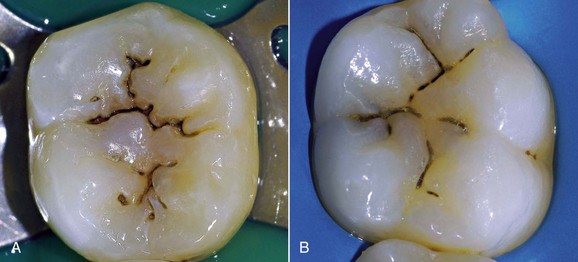

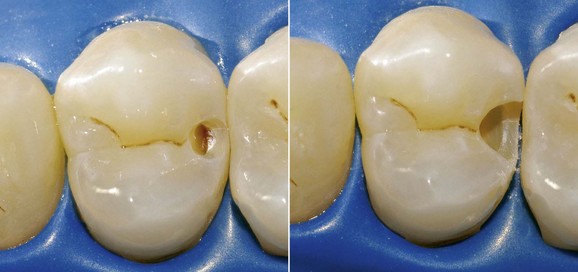

On the level of pits and fissures (Figure 1-60) the affected enamel is brown in appearance (dark areas), and the development toward cavitation and subsequent involvement of the underlying dentin is often difficult to assess clinically.

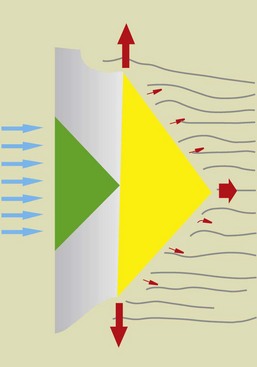

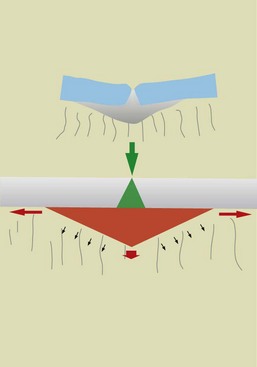

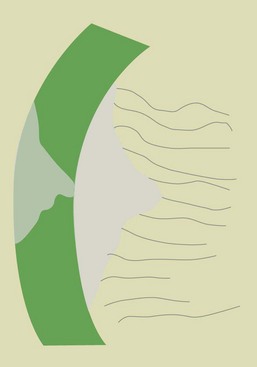

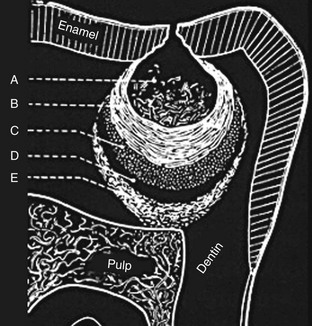

The microscopic evaluation of carious lesions on smooth enamel surfaces exhibits a triangular pattern (conical section) with the apex pointing toward the dentin (Figure 1-61).

With pits, the lesion has always a triangular shape, but in this case the apex is directed outward, whereas the base of demineralization faces the dentinal substrate (Figure 1-62).

In both situations, especially in the case of initial lesions, the outer surface is seemingly intact, making it difficult for the clinician to arrive at an accurate assessment of the real involvement of the underlying tissues (Figure 1-63).

Dentin Caries

Macroscopically, dentin caries is traditionally and didactically classified into two forms:

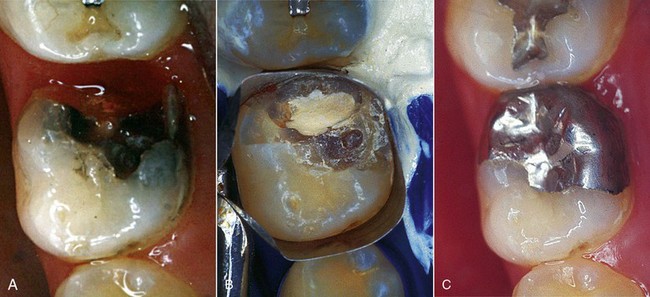

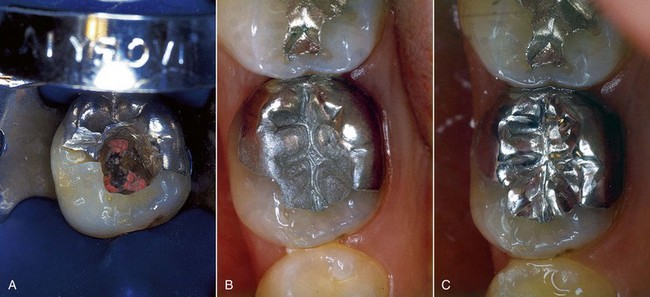

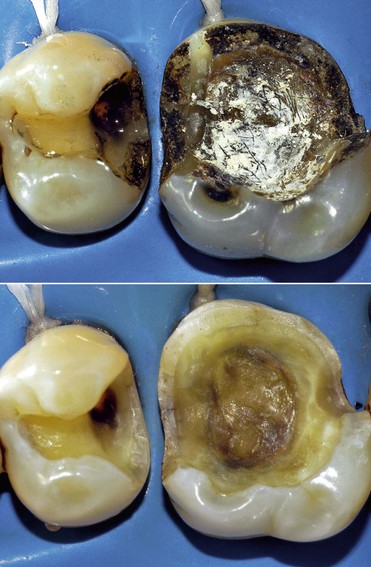

• An “acute” progressive form, which evolves rapidly, typical of active lesions of young teeth, with a white or yellowish-brown appearance and a soft consistency (Figure 1-64).

• A “chronic” form or arrested caries, usually found in adult teeth, which progresses slowly. It has a blackish-brown color, and its consistency is harder and drier compared with the active carious lesions seen in young teeth (Figure 1-65).

Microscopically, dentin caries has a distinctive conical shape, with the apex of the lesion directed toward the pulp (see Figures 1-61 to 1-63). Some authors divide carious progression into three distinct phases:

Carlier’s schematic diagram (1954) shows the five characteristic zones of dentin caries, distinguishing—in a crown-apical direction—a “disorganized” outer layer followed by a “soft” dentin one, an area of bacterial invasion, and a deeper “clear” area with initial obliteration of dentinal tubuli, which is followed by the last layer, consisting of “hard” dentin, indicating pulp reactivity (Figure 1-66).

Topographic Classification

• Class I—Morphologic depression, pits and fissures of posterior teeth (Figure 1-67), pits and foramina ceca of anterior teeth (Figure 1-68)

• Class II—Interproximal caries lesions of molars and premolars (Figure 1-69)

• Class III—Interproximal cavities of incisors and canines, with no involvement of the incisal angle (Figure 1-70)

• Class IV—Interproximal cavities of incisors and canines, with involvement of the incisal angle (Figure 1-71)

• Class V—Cavities involving the buccal or lingual gingival third of any tooth (Figure 1-72)

Based on location, caries lesions are classified as follows:

• Site 1: Pits on occlusal surfaces of posterior teeth and smooth surfaces of anteriors

• Site 2: Approximal surfaces, contact points

• Site 3: Cervical one third of the crown or of the exposed root

Together with the site, the size of the lesion is also taken into account:

Symptomatologic Classification

Incipient caries of the enamel exhibits the following characteristics:

• Dark pigmented areas within the pits (Figure 1-73)

Figure 1-73 Initial enamel caries of the occlusal grooves.

• Whitish milky areas on smooth surfaces, especially the interproximal aspects

Clinical Classification

• Initial caries—No cavitation, appears as a whitish, rough and chalky spot lesion involving only the enamel; it is the only type of caries that can be reversed by fluoride (Figure 1-74).

• Superficial caries—It extends beyond the amelodentinal junction and therefore initiates dentin invasion (Figure 1-75).

• Deep caries—It extends apically and affects the dentinal body of the tooth (Figure 1-76).

• Penetrating caries—It causes a reaction of the pulp-dentin complex with formation of tertiary dentin (Figure 1-77).

• Perforating caries—It entails exposure of the pulp (Figure 1-78).

, degree 3 (probing more than 3 mm; completely passes through the furcation).

, degree 3 (probing more than 3 mm; completely passes through the furcation).