Management of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) can be challenging for the oral and maxillofacial surgeon. The incidence of skin cancer is increasing with the aging population, and treatment decisions must be individualized for every patient. Surgical excision remains the ‘gold standard’ treatment of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Once the cutaneous malignancy is completely excised, multiple reconstructive options exist. Reconstructive goals include preservation of facial function and cosmesis. Facial reconstruction can be achieved with a variety of surgical options that camouflage defects and preserve important anatomic structures. Postoperatively, careful wound management and close follow-up can minimize long-term complications and recurrence.

Etiopathogenesis/Causative Factors

With more than 1 million cases diagnosed each year, NMSC has become the most common malignancy in the United States. Recent studies have indicated that patients with NMSC are younger and have multiple lesions throughout their lifetime. Approximately 80% of all skin cancer diagnoses are BCC, with a BCC/SCC ratio of 4 : 1 ( Fig. 110-1 ). The cause of NMSC is multifactorial. Frequent exposure to ultraviolet radiation, which is capable of inducing DNA mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene, is the primary causative factor. Other well-documented risk factors include fair skin, light eyes and hair, older age, male sex, and immunosuppression. Patients with a diagnosis of NMSC are also at high risk for the development of a second lesion. Meta-analysis of subsequent NMSC diagnoses has demonstrated a 44% chance of subsequent BCCs developing and an 18% chance for subsequent SCCs. Finally, actinic keratoses and Bowen disease (SCC in situ) are common precursors of SCC in patients with increased sun exposure. These patches of irregular, scaly plaques serve as an indication for long-term skin surveillance.

Pathologic Anatomy

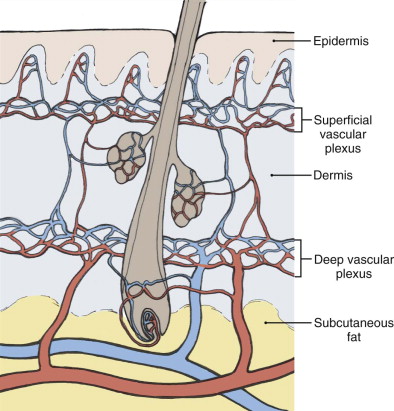

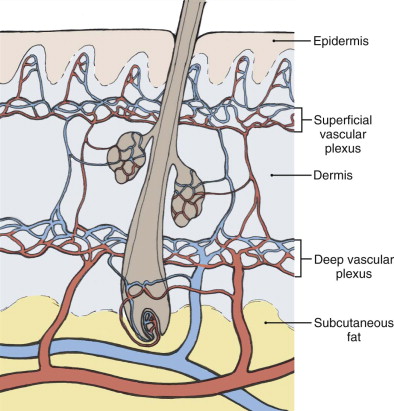

Surgical excision in the head and neck region requires careful preoperative planning and a thorough understanding of reconstructive options. Facial anatomy, sensation, and function should be preserved while ensuring complete removal of the malignant lesion. The skin is composed of both a superficial and deep vascular plexus between the dermis and subcutaneous fat ( Fig. 110-2 ).

The blood supply to the face is derived from branches of the external and internal carotid arteries with rich collateral networks. Although the face is highly vascularized and adaptable, limitations do exist. The surrounding skin color, texture, hair growth, and anatomic structures must be carefully considered. Reconstruction of a wound should not compromise function, esthetics, or blood supply.

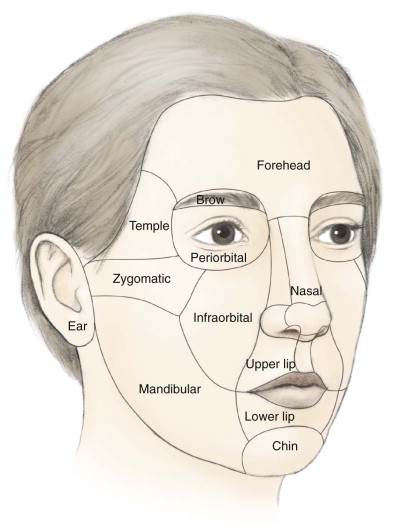

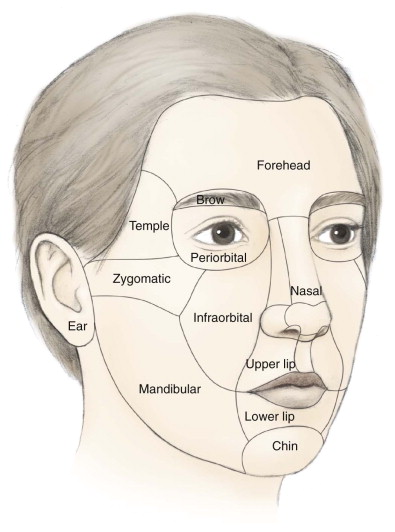

Facial cutaneous defects can be categorized into well-known esthetic units: forehead, periorbita, nose, cheek, lip, chin, ear, and scalp ( Fig. 110-3 ). These units have both advantages and limitations in surgical reconstruction that must be considered preoperatively.

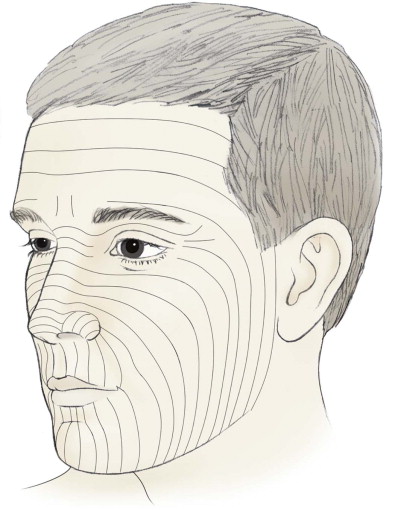

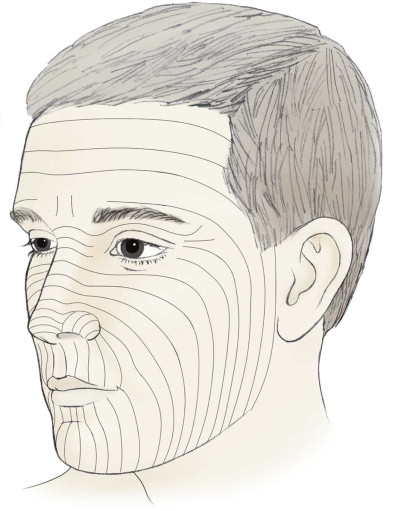

The skin also adapts to repetitive contracture of facial muscles by forming relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs). These lines or creases correspond to the insertion of facial musculature into the overlying dermis ( Fig. 110-4 ). Careful placement of incisions within subunit margins and RSTLs can skillfully mask an oncologic reconstruction.

Pathologic Anatomy

Surgical excision in the head and neck region requires careful preoperative planning and a thorough understanding of reconstructive options. Facial anatomy, sensation, and function should be preserved while ensuring complete removal of the malignant lesion. The skin is composed of both a superficial and deep vascular plexus between the dermis and subcutaneous fat ( Fig. 110-2 ).

The blood supply to the face is derived from branches of the external and internal carotid arteries with rich collateral networks. Although the face is highly vascularized and adaptable, limitations do exist. The surrounding skin color, texture, hair growth, and anatomic structures must be carefully considered. Reconstruction of a wound should not compromise function, esthetics, or blood supply.

Facial cutaneous defects can be categorized into well-known esthetic units: forehead, periorbita, nose, cheek, lip, chin, ear, and scalp ( Fig. 110-3 ). These units have both advantages and limitations in surgical reconstruction that must be considered preoperatively.

The skin also adapts to repetitive contracture of facial muscles by forming relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs). These lines or creases correspond to the insertion of facial musculature into the overlying dermis ( Fig. 110-4 ). Careful placement of incisions within subunit margins and RSTLs can skillfully mask an oncologic reconstruction.

Diagnostic Studies

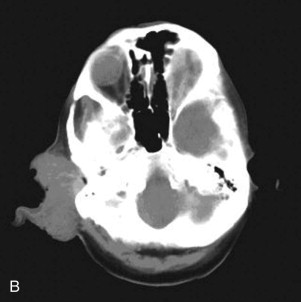

Laboratory tests and radiographic imaging studies are often not indicated for simple NMSC of the head and neck region. A diagnosis of NMSC must be obtained from a biopsy of the lesion. Ideally, the specimen chosen is from the most representative area of the lesion. Surgical diagnostic options include shave, punch, incisional, and excisional biopsy. If the lesion is suspected to violate deep structures such as muscle or periosteum, computed tomography with intravenous contrast enhancement is warranted ( Fig. 110-5 ). The incidence of metastasis in patients with NMSC is less than 1% for BCC but can be as high as 20% for cutaneous SCC of the head and neck region. Larger, invasive lesions require aggressive surgical excision and possibly lymph node dissection.

Shave biopsies are useful for exophytic lesions in the epidermis or superficial dermis ( Fig. 110-6 ). A punch biopsy includes dermis and subcutaneous fat for extended histologic examination. Three-millimeter to 4-mm punch biopsies are usually adequate to obtain an appropriate histologic sampling of a suspicious skin lesion. Incisional and excisional biopsies are often used for larger lesions or inflammatory/ulcerative lesions in which comparison to normal skin is desirable. These excisions are usually elliptic in nature. Once a diagnosis of NMSC has been made, surgical treatment options can be considered.

Treatment Goals

The goals of treatment are to completely remove the malignant lesion and preserve normal function and appearance of the face. Although surgical excision of NMSC is the gold standard, ablative options also include cryotherapy, curettage and electrodesiccation, laser ablation, photodynamic therapy, radiation therapy, topical 5-fluorouracil, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Surgical excision of a BCC or SCC involves removal of the lesion along with adequate margins of normal tissue to ensure complete removal of malignant pathology. Reported recommendations for adequate surgical margins vary from 2 to 10 mm. For lesions smaller than 2 cm, studies have demonstrated that more than 96% are completely excised with 4-mm margins. Smaller lesions can be excised with slightly smaller margins, whereas lesions larger than 2 cm require margins up to 1 cm.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses