Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

The palatal flap is an axial flap based on the greater palatine artery. It can be used as a rotation flap or an interpolated flap with an intervening bridge of oral epithelium. Its first reported description was credited to Ashley in 1939. Since then, several authors have demonstrated the use of this flap and its modifications in closure of oroantral fistulas, oronasal fistulas, and a variety of small to medium ablative defects. In 1966, Moore and Chong described the use of the “sandwich” palatal island flap for palatal lengthening in the treatment of hypernasal speech. Henderson expanded on the use of the palatal island flap based entirely on the greater palatine artery in the closure of oroantral fistulae. This has led to increased flap mobility.

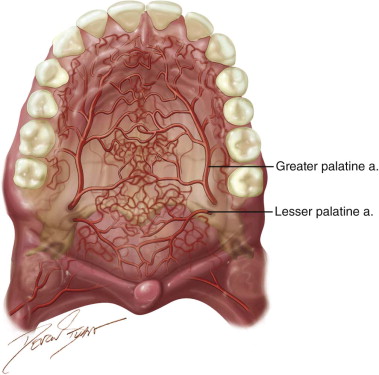

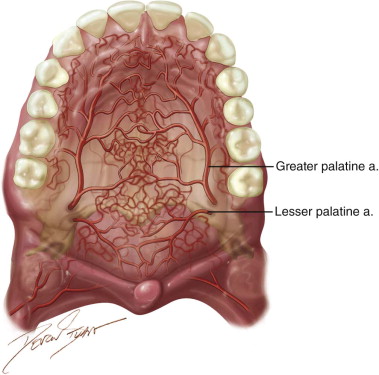

In 1977, Gullane and Arena used the total palatal island flap based unilaterally on one single greater palatine artery with 180 degrees rotation for large ablative oral defects. This was supported by Maher’s anatomic studies in 1977, which demonstrated a “macronet” of submucosal vessels forming anastomoses between the right and left palatal arteries ( Figure 109-1 ). This technique was reevaluated by Genden and colleagues in 2001 with 100% success in five cases. Alternatively, the flap may be de-epithelialized and inverted posteriorly. Reports on this technique have noted complete donor site reepithelialization by 4 weeks in all cases.

In 2003, Anavi and colleagues reported good outcomes in a series of 63 patients with oroantral fistulas treated with a palatal rotation-advancement flap. They reported on the use of this axial flap for defects as large as 2 cm × 4 cm.

Advantages include location adjacent to defect site, similar or “like” tissue, good vascularity, maintenance of sensory innervation, adequate thickness, minimal donor site morbidity, simple anatomy, and short procedure time.

History of the Procedure

The palatal flap is an axial flap based on the greater palatine artery. It can be used as a rotation flap or an interpolated flap with an intervening bridge of oral epithelium. Its first reported description was credited to Ashley in 1939. Since then, several authors have demonstrated the use of this flap and its modifications in closure of oroantral fistulas, oronasal fistulas, and a variety of small to medium ablative defects. In 1966, Moore and Chong described the use of the “sandwich” palatal island flap for palatal lengthening in the treatment of hypernasal speech. Henderson expanded on the use of the palatal island flap based entirely on the greater palatine artery in the closure of oroantral fistulae. This has led to increased flap mobility.

In 1977, Gullane and Arena used the total palatal island flap based unilaterally on one single greater palatine artery with 180 degrees rotation for large ablative oral defects. This was supported by Maher’s anatomic studies in 1977, which demonstrated a “macronet” of submucosal vessels forming anastomoses between the right and left palatal arteries ( Figure 109-1 ). This technique was reevaluated by Genden and colleagues in 2001 with 100% success in five cases. Alternatively, the flap may be de-epithelialized and inverted posteriorly. Reports on this technique have noted complete donor site reepithelialization by 4 weeks in all cases.

In 2003, Anavi and colleagues reported good outcomes in a series of 63 patients with oroantral fistulas treated with a palatal rotation-advancement flap. They reported on the use of this axial flap for defects as large as 2 cm × 4 cm.

Advantages include location adjacent to defect site, similar or “like” tissue, good vascularity, maintenance of sensory innervation, adequate thickness, minimal donor site morbidity, simple anatomy, and short procedure time.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

Although many authors advocate the primary use of a Rehrman’s buccal advancement flap for the closure of oroantral fistula, an axial palatal rotation flap is reserved as an option for failed repairs and large communications. As noted previously, the palatal flap carries its own blood supply from the greater palatine artery and is a reliable, locally available source of highly bound oral mucosa. Use of this flap prevents obliteration of the buccal vestibule where future denture use is planned. It has been successfully used for reconstruction of sizable ablative oral defect of the maxillary alveolus and tuberosity, hard palate, anterior soft palate, retromolar trigone, and tonsillar fossa.

In pediatric patients with oronasal fistulas secondary to failed cleft palate repair, anterior defects of the hard palate may be repaired with a palatal rotation flap and nasal side closure. This is an option provided that one of the greater palatine arteries is intact and that adequate adjacent hard palate tissue is available. Other options include the anteriorly based tongue flap and the facial artery myomucosal flap.

Lastly, the palatal rotation flap may be considered in the management of acquired oronasal fistulas, which may be secondary to ablative defects, trauma, infection (i.e., tertiary syphilis), autoimmune vasculitis (i.e., Wegener’s granulomatosis), or the use of illicit substances such as cocaine.

Limitations and Contraindications

In some of the above-mentioned indications, compromise of the descending or greater palatine artery secondary to prior palatoplasty or traumatic injuries is a distinct possibility and may be a contraindication. The availability of a patent greater palatine artery must be confirmed prior to raising a palatal flap. Otherwise the flap is raised as a random pattern flap limiting the possible length-to-width ratio.

As with any surgical procedure, careful patient selection requires good clinical judgment and an appreciation for the social, medical, and surgical components that make each case unique. Concerns for a patient’s ability to tolerate a secondary flap inset procedure or follow home care instructions may be relative contraindications. Medical comorbidities that may compromise healing include tobacco smoking, use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) , or coagulopathies.

Large defects of the palate or maxilla (>1.5 to 2 cm) may require a prosthetic reconstruction or other local, regional, or distant flaps. Examples include the anteriorly based tongue flap, the temporoparietal fascia flap, and radial free forearm flap, respectively.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses