Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

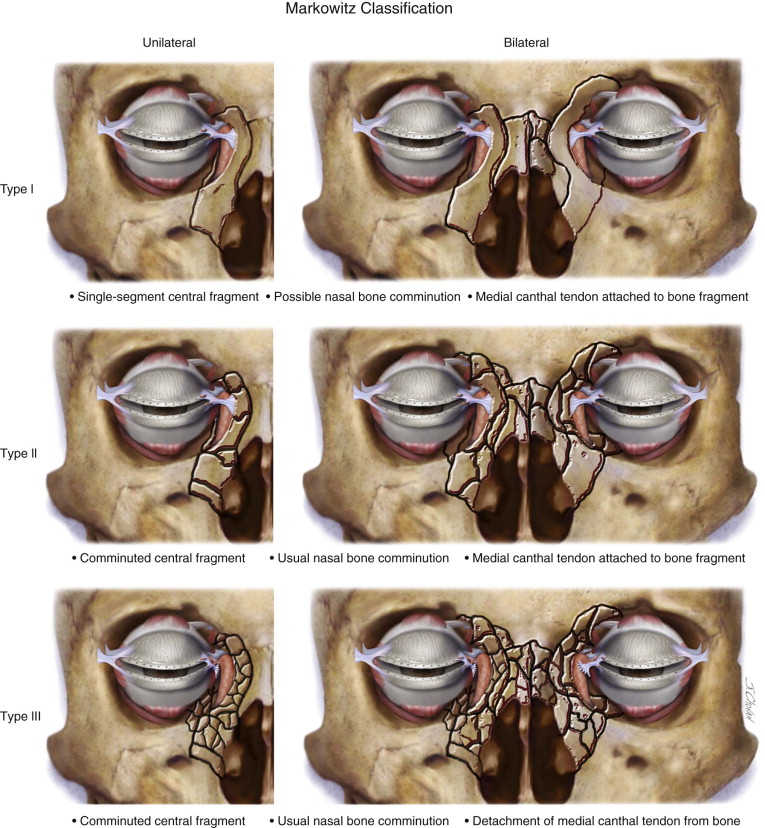

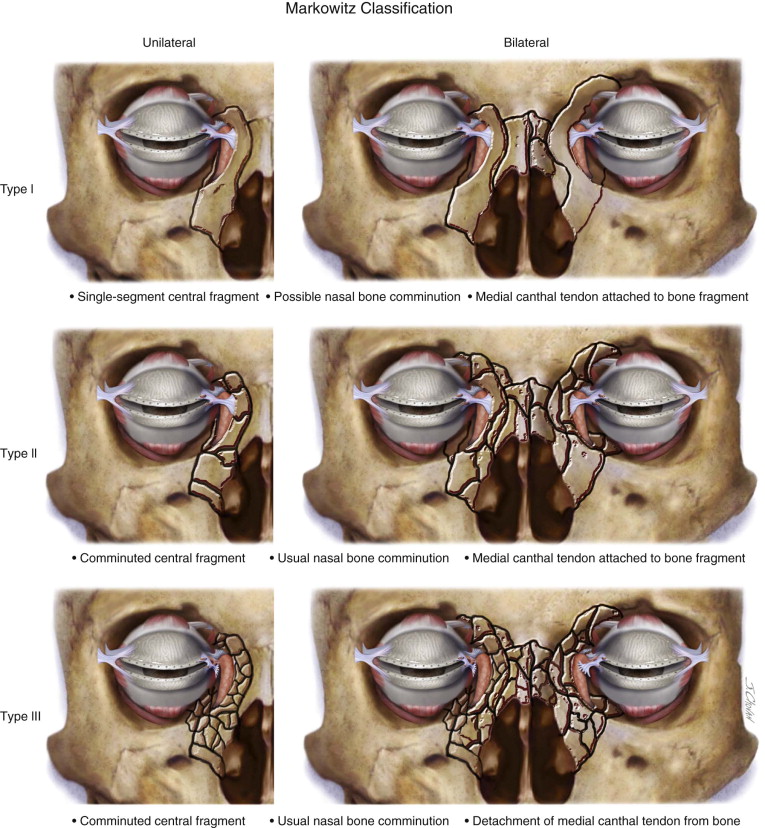

Naso-orbito-ethmoid (NOE) fractures are complex injuries that affect the central midface. The intricate anatomy of the osseous and soft tissue components of this area makes surgical access and repair technically challenging. These injuries are typically a result of high-impact facial trauma and rarely occur in isolation. The nomenclature, classification, and treatment techniques for these injuries have undergone transformation in recent decades. In 1970, Stranc termed these injuries “naso-ethmoid” fractures. In 1973, Epker coined the term “naso-orbito-ethmoid” fracture, which is still the more popular term today. Markowitz et al preferred the term “nasoethmoid orbital” fractures. Classification of the fracture pattern has evolved since Stranc’s initial attempt in 1970. In 1985, Gruss suggested a further classification, but it was Markowitz and Manson who published a diagnostic classification in 1991 that is still widely used today. Their system is based on the fracture pattern and degree of comminution and medial canthal tendon (MCT) attachment/disruption. Injuries are further classified as unilateral or bilateral and whether there is extension into other anatomic locations. This classification has the advantage of helping to guide management options. The classification is as follows ( Figure 75-1 ) :

- •

Type I: Single-segment central fragment

- •

Type II: Comminuted central fragment with fractures external to the medial canthal tendon insertion

- •

Type III: Comminuted central fragment with fractures extending into bone bearing the canthal insertion

Before 1960, the treatment of NOE fractures involved the use of external splinting devices. However, these methods failed to address the medial canthal tendon and thus have fallen out of favor. Mustarde in 1964 and Dingman in 1969 both demonstrated superior results with open reduction and internal fixation using wire osteosynthesis. The development of internal fixation systems and advanced imaging techniques has led to the use of open reduction and internal fixation with plating techniques for these injuries, with improved functional and esthetic results.

History of the Procedure

Naso-orbito-ethmoid (NOE) fractures are complex injuries that affect the central midface. The intricate anatomy of the osseous and soft tissue components of this area makes surgical access and repair technically challenging. These injuries are typically a result of high-impact facial trauma and rarely occur in isolation. The nomenclature, classification, and treatment techniques for these injuries have undergone transformation in recent decades. In 1970, Stranc termed these injuries “naso-ethmoid” fractures. In 1973, Epker coined the term “naso-orbito-ethmoid” fracture, which is still the more popular term today. Markowitz et al preferred the term “nasoethmoid orbital” fractures. Classification of the fracture pattern has evolved since Stranc’s initial attempt in 1970. In 1985, Gruss suggested a further classification, but it was Markowitz and Manson who published a diagnostic classification in 1991 that is still widely used today. Their system is based on the fracture pattern and degree of comminution and medial canthal tendon (MCT) attachment/disruption. Injuries are further classified as unilateral or bilateral and whether there is extension into other anatomic locations. This classification has the advantage of helping to guide management options. The classification is as follows ( Figure 75-1 ) :

- •

Type I: Single-segment central fragment

- •

Type II: Comminuted central fragment with fractures external to the medial canthal tendon insertion

- •

Type III: Comminuted central fragment with fractures extending into bone bearing the canthal insertion

Before 1960, the treatment of NOE fractures involved the use of external splinting devices. However, these methods failed to address the medial canthal tendon and thus have fallen out of favor. Mustarde in 1964 and Dingman in 1969 both demonstrated superior results with open reduction and internal fixation using wire osteosynthesis. The development of internal fixation systems and advanced imaging techniques has led to the use of open reduction and internal fixation with plating techniques for these injuries, with improved functional and esthetic results.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

Indications for use of the procedure include the following:

-

Instability of canthal-bearing bone or avulsion of medial canthal tendon

-

Loss of nasal projection and support

-

Comminution of medial orbital wall component

-

Interruption of lacrimal drainage

-

Concomitant facial fractures undergoing repair

Limitations and Contraindications

There are few strict contraindications to treatment of NOE fractures. Those that apply to any facial fracture include a hemodynamically unstable patient, acute neurologic hemorrhage, and pending demise. Contraindications that may apply specifically to a NOE fracture include an open globe injury and traumatic hyphema.

Limitations to repair depend principally on the ability to reduce and fixate the involved structures. In significant midfacial injuries, such as those with gross avulsion of tissue due to gunshot wounds, repair is limited to soft tissue closure. Minimal or no bony reduction and fixation is possible.

Technique: NOE Fixation with Canthal Barb Suspension

A sequential approach to the repair of a NOE fracture is important so that all elements of the injury are addressed. The following sequential approach, provided by Ellis, is widely used:

- 1.

Expose fractures completely

- 2.

Identify canthal-bearing bone or MCTs

- 3.

Reduce or stabilize medial orbital rims

- 4.

Reconstruct internal orbit

- 5.

Perform transnasal canthopexy as required

- 6.

Reduce septal fractures

- 7.

Reconstruct bony dorsum

- 8.

Perform soft tissue reduction

Step 1:

Exposing the Fracture

Type I fractures with minimal displacement may be addressed through a vestibular incision alone. Local anesthetic can be infiltrated in the maxillary vestibule from first molar to first molar. The incision begins through the mucosa and then is directed perpendicular toward bone. After the incision, elevation of the subperiosteal pocket from one zygoma to the other and up to the infraorbital rims is performed. Care in identification of the piriform rim is important to avoid violating the nasal mucosa.

Type II and type III fractures require coronal exposure. For adequate visualization during coronal exposure, it is recommended that the patient be positioned using a Mayfield headrest attachment on the operating room table. The table may be placed in a reverse Trendelenburg or lawn chair position to aid in correct positioning. Routine shaving is not required unless intracranial access is necessary in conjunction with a neurosurgeon.

With a marking pen, the surgeon marks a “lazy S ” from the helical root of one ear to the contralateral ear approximately 4 cm behind the hairline. This curvature aids in postoperative camouflage of the incision. Lidocaine with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine is injected along the proposed incision in a subcutaneous plane. Midline and paramedian markings are made with the scalpel to aid reapproximation during closure. The incision is started with a #10 or #15 scalpel blade through skin, subcutaneous tissue, and galea until the periosteal layer is identified. Once the subgaleal plane has been identified, it may be bluntly dissected with a curved hemostat or Metzenbaum scissors toward one of the root helices. Maintaining the instrument in this plane, the surgeon continues the incision from skin down to the instrument. This incision is completed from ear to ear.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses